Paul LePage’s first memory is of his house nearly burning down.

Of his father, LePage’s earliest recollection is the man kicking him on the ground.

And of his siblings, he recalls tripping over the body of a brother who died one night in their Lewiston tenement.

Although LePage is reluctant to revisit the violence and tragedy that defined his upbringing, the 19 years between his birth and when he entered college stand as some of the most influential in shaping how Maine’s governor understands the world. In his attitudes and worldview, no other period has drawn deeper demarcations of right and wrong, tough love and self-discipline.

From the materials of his own experience, LePage forged a viewpoint on how one ought to succeed in modern society, crafting a formula in which the power of personal responsibility will always trump the ability of government to help. Although he is certainly not alone in this understanding, from its basic tenets he has drawn both high praise and deep criticism, as he attempts to overturn what has been a 50-year government campaign to ease social ills through direct assistance.

For nearly 90 minutes in an unprecedented interview, LePage agreed to talk about his hardscrabble upbringing, his deeply dysfunctional family and how he managed to claw his way out of poverty and start his life anew, aided by benefactors who helped him further his education.

“My life started the day I walked into Husson College,” LePage said. “I wouldn’t want to live a day before it. That is where my life started. Before it was nightmares, and to this day, I still have the same nightmares.”

More so than for his gubernatorial opponents – U.S. Rep. Mike Michaud and independent candidate Eliot Cutler – LePage’s early life has played an outsize role in his introduction to the Maine public.

Through the telling and retelling of stories about his early years as the poor son of an abusive father growing up in a family of 18 kids in Lewiston, to the toil and luck that allowed him to survive after he fled his home, his supporters have returned to the idea of LePage as an authentic voice in state politics – the anti-politician, the everyman, the one who still remembers what true struggle feels like, and who, miraculously, found the keys to personal prosperity.

‘WHEN THE BAD TIMES STARTED’

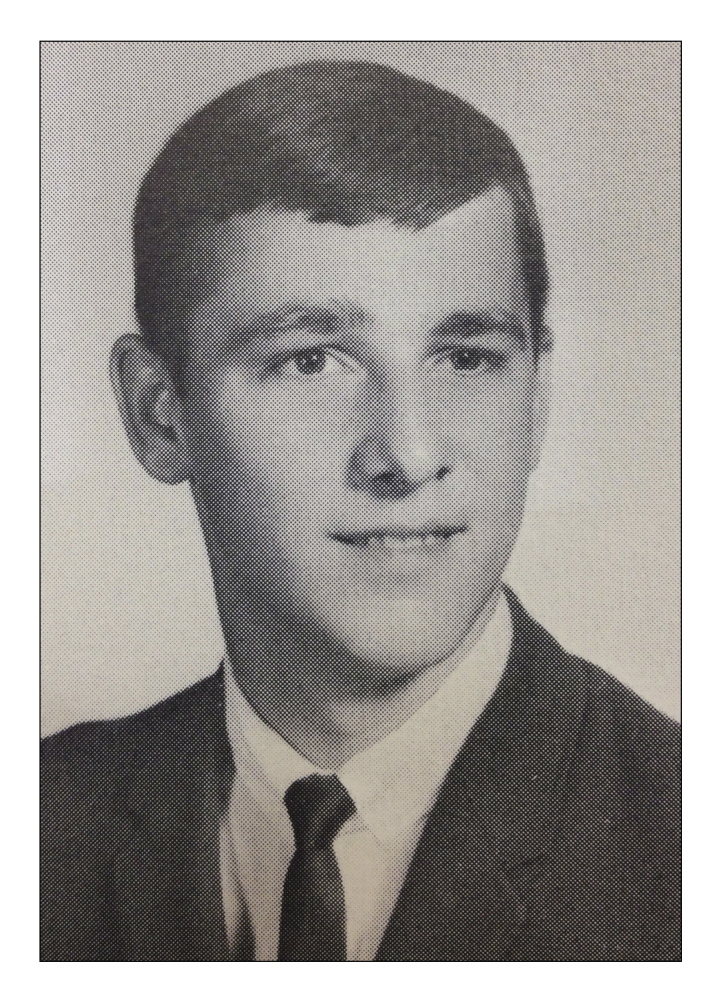

Paul Richard LePage was born in Lewiston on Oct. 9, 1948, to Gerard and Teresa LePage.

At 10 pounds, 9 ounces, he would be the smallest at birth of his brothers and sisters, LePage said.

LePage’s recollections about his life begin in Turner, around age 3, when the family spent a winter living in the home of LePage’s grandfather, who had recently died. When spring came, LePage said, he remembers the house catching fire, sending the family back to Lewiston.

“That’s when the bad times started, really,” he said.

The family rented a small house on Lisbon Road about the time LePage started kindergarten. Soon, the family moved to 115 Lincoln St., and then again to an apartment building nearby at 215 Lincoln St., in Lewiston’s Little Canada neighborhood.

As Franco-American Catholics, neither of his parents believed in contraception, so the LePage clan grew almost annually.

“She just was a baby machine,” LePage said of his mother. “She tried the best she could. She was a wonderful mom.”

The apartment was cramped, and there was no shower. The only sink was in the kitchen.

At night, the children were packed five or six to a bed, sleeping head to foot. The tight quarters were not uncommon; at one point, LePage said, 88 children lived in his 12-unit building.

His father worked at the Bates Mill until it closed, and later as a painter and a general laborer, according to a 2012 Portland Phoenix story.

Both of his parents were of French-Canadian descent and spoke mostly French. The same went for classes at St. Mary’s grammar school.

“Every course was in French,” LePage said. “The only course you got in English was English. And that was by a brother or a nun who wasn’t really good in English.”

Paul Labbe, 65, of Lewiston, who attended grammar school and high school with LePage, said the parochial education was strict.

“You really have to behave,” Labbe said. “The brothers didn’t take any crap from anybody.”

Among his parents and siblings, LePage was the only one to complete eighth grade, he said.

At the time in Lewiston, depending on whom you asked, Little Canada was either a place to be avoided after dark, or a tight-knit community with limited means.

People looked out for one another, Labbe said. One family would marry into another, so cousins were never far. The Catholic faith was central and the church doors were never locked.

In the midst of the struggle, some adults turned to alcohol, including LePage’s father.

“It was not an uncommon thing in the Lewiston-Auburn area with the mill families, for there to be alcohol abuse problems, and the kids taking the brunt of it,” said Ronald Paradis of Lewiston, a high school classmate of LePage who learned of LePage’s rough upbringing when he ran for governor.

As early as LePage can remember, his father beat him when he drank.

“He was actually, Monday through Friday, he was a great guy,” LePage said. “He worked hard and he tried to provide the best he could on minimum wage.”

When the week was over, Gerard LePage drank heavily, stopping only when he had to return to his job on Monday.

The abuse came to a head one Sunday night in 1959, when Paul LePage’s father sat the 11-year-old in a kitchen chair and slapped him over and over until he knocked the boy from his seat.

“Then I fell on the floor and he started kicking, and then the neighbor heard it, and came in and stopped it,” LePage said.

LePage’s nose and jaw were broken. Gerard LePage gave his son a 50-cent piece, and told him to tell the hospital staff he fell down the stairs.

“I said, ‘Nope, I’m outta here,’ ” the governor recalled. “Running away at 11 saved my life. Because after that, the people I ran into were all good people.”

GOOD LUCK AND HARD WORK

By the time LePage fled his family life at 11, he was already working odd jobs when he wasn’t in school.

He delivered groceries for a neighborhood market, and over time befriended the driver of a Pepsi-Cola truck.

The relationship with the driver started when he would ask LePage, then 10 years old, to gather up empty glass bottles for him in return for a free soda.

The two worked together for one summer before the driver quit. Although he did not know it at the time, the driver’s departure would eventually lead LePage out of misery.

The replacement, Bruce Myrick, took over the Pepsi route and befriended LePage. When LePage fled his home, Myrick came looking for him.

“He came to get me one time and I was gone,” LePage said. “Then he found me, and he started helping.”

Myrick took LePage in, allowing him to sleep at the family’s Auburn home a few nights a week.

Although paramount in LePage’s life, the Myricks were only a part of the informal social safety net that caught the future governor when he fell into homelessness.

Although he no longer stayed with his family, LePage remained in contact with his mother and his siblings. One day in 1961, when LePage was about 13, a brother asked LePage if he could fill in for him as a dishwasher at a neighborhood restaurant, Theriault’s Cafe. He jumped at the chance.

“The owners recognized that I was pretty good at what I was doing, and so they wanted to keep me on,” he said.

The proprietors, Eddie and Pauline Collins, moved LePage to the bakery, and soon LePage was spending time at their apartment in Little Canada, sleeping there during the weekdays. More than a place to lay his head, the Collinses’ and the Myricks’ households gave him love, support and discipline. LePage, grateful, gobbled it up.

“They became my family, they mentored me,” LePage said. “Pauline (Collins) was sort of the mother in my life. She treated me like I was one of her kids. I had to do my bed, I had to take a shower, I had to do my homework, you know, that kind of stuff. That’s the kind of tough stuff I wasn’t used to.”

Meanwhile, back on Lincoln Street, the remaining LePage siblings were not as lucky. Some would walk far rockier life paths, and according to LePage, landed again and again on the welfare rolls, or worse.

LESSONS FROM DYSFUNCTION

Today, LePage’s relationships with his siblings are fraught with complexities.

Some have passed away, including Norman, the 4-year-old brother whose body LePage tripped over inside the family’s darkened apartment one night in Lewiston. The boy succumbed to acute gastroenteritis after suffering there for days, according to the 2012 Phoenix story.

Another brother died five years ago, LePage said. Another died of complications from the AIDS virus. He lost a sister, too, but didn’t say how or when.

Others siblings, meanwhile, have been convicted of crimes and incarcerated. Asked how many have spent time in jail, LePage said “many,” before rattling off five names.

The tension has occasionally spilled into public view. In the spring of 2013, when a rash of arson fires in Lewiston displaced dozens of residents, one of LePage’s convict brothers was among them.

“I remember I was being criticized for having a brother in one of the fires … that I wasn’t helping him,” LePage said. “I didn’t help him and I wouldn’t help him. … He did things to little girls that I didn’t like, and served a lot of time in prison for it, so I just couldn’t deal with him.”

Some of the familial fallout stemmed from distrust. Before LePage’s father died in 2005, a sister had taken him into her Florida home to care for him. But LePage heard from others that she may have abused him. He had law enforcement look into it, effectively destroying his relationship with the sister.

Shortly before his father’s death, LePage flew to Florida, but his sister refused to let him see his father. When his father died a short time later, the same sister refused to allow LePage to attend the funeral, LePage said. As a final insult, she excluded him from the obituary.

As an adult, LePage’s relationship with many of his siblings deteriorated for other reasons. He said some of them treated him – the most financially secure of the children – like “Bank of America.”

Time and again, they would come to him with their needs, and time and again, LePage agreed to help out. Yet he described how his family members would take from him what they could and disappear.

One February in the 1970s, a brother called LePage asking for help to pay a $324 heating bill. The gas had been shut off and he had two kids at home. It was a Friday, and LePage expedited a check to his brother. He also explained that it is illegal to shut off someone’s heat in the winter. All his brother had to do was visit City Hall and insist they turn it back on.

“So what’s he do Monday morning? Very first thing, he goes to City Hall, (and the utilities) turn it right back on.”

With the check from LePage, his brother bought a stereo.

“In generational poverty there is a mind-set that everyone wants to get what everyone else has as quick as possible. … So what they do, the minute they get a few bucks, they go buy a smartphone or they go buy something of status, and that stereo was an item of status,” LePage said. “If you help without tough love, they’re going to take advantage. And it’s my family. I’m not trying to be a ding-a-ling and be tough on people. I’m trying to do it the right way, because if you don’t do it the right way, and I have 50 years’ experience, it won’t work.”

EDUCATION IS THE KEY

The Collins family and the Myrick family made sure LePage went to school – a method of support that had the greatest influence on him later in life.

School was not his only responsibility, though. At the Collinses’ bakery, LePage would rise before dawn on school days to prepare that day’s confections, only to return after his classes let out to clean up the kitchen and grease the tins for the next day’s batches.

Several high school classmates said they remember LePage as reserved but personable; he was often too busy working after school to play sports or to engage in extracurricular activities.

One classmate, Peter Longley, who shared homeroom with LePage, said he does not remember the governor as particularly social, owing in part to his rigorous work schedule, and also to his heavy French accent.

“Socially, I think he was probably more concerned with where the next meal was coming from,” Longley said.

By the time he was ready to graduate, Bruce Myrick had already introduced LePage to Peter Snowe, who owned a concrete plant in Auburn. Snowe, along with Thomas Anthoine, the owner of a rubber factory, would help LePage win entrance to college, and then with paying for the education. (Snowe was future U.S. Sen. Olympia Snowe’s first husband.)

LePage applied to 50 schools, he said, but his verbal SAT score was lackluster.

“My verbals were bad,” LePage said. “But I figured, they gotta give me a shot. Because the Collinses had given me a shot. The Myricks had given me a shot. Tommy Antoine gave me a shot. If I just play it straight and narrow, someone will give me a shot.”

No one bit.

Then, a friend from Little Canada, Roland Moreau, who remains one of LePage’s closest friends, was accepted to Husson College in Bangor.

LePage worked up the nerve to call the college’s admissions office and was granted an audience with Chesley Husson Sr., the college’s founder. They talked for an hour, and Husson made him a deal.

Husson offered a chance for LePage to take an achievement test in French. “I scored 724, and he said, ‘You’re in,’ ” LePage said.

Despite the pressure to perform and the debt he was incurring, LePage’s social life bloomed.

His previous experience of hard living had matured him, and students flocked to him for advice or for help.

“I was the old man,” he said. “When I was at Husson everybody around me were 18-year-olds but they were acting like they were 15-year-olds. I was a 19-year-old acting like a 30-year-old.”

He joined a fraternity, Mu Sigma Chi, whose members were mostly of French-Canadian descent. For one semester, before the college moved to a new location outside of Bangor, the fraternity brothers lived in a large house on Cumberland Street. The brothers lost the house, though, after an administrator called one Saturday morning and a woman answered. It was forbidden to have women on the second floor, where the phone was located, and the college moved the young men to dormitory-style housing.

Today, the former fraternity house is a halfway house for alcoholics. Ironically, if anyone living there punched through a wall, “they’d get a lot of empties,” LePage said, laughing.

He joined club after club and dipped his toes into student politics, winning election first to the student senate and then as the vice president and president of his class. He helped start the campus’s first real newspaper, The Spectator Weekly, which he said in an editorial in its inaugural issue would “not only help stamp out the communications gap, but will furnish a real newspaper to the students, faculty, and administrators.” He wrote later: “Only if the members of our college community will support this supplement can we conquer and destroy the apathy that surrounds us.”

It was a provocative time – the Vietnam War was raging, and unless students kept their grades up, they could risk losing their student deferment from the draft. For LePage, not only would he risk losing the support of his benefactors, but he, like many others, could have been sent to the jungles of Southeast Asia.

At the student newspaper, LePage took on the role as business manager, hustling for advertising dollars to keep the publication afloat.

“We bartered for the printing,” he said. “It was really sort of fun, because those days were purely out-of-the-box thinking. If it worked, fine, if it didn’t, you tried something else. The only penalty for failing is you learn, which is what it’s all about.”

Snowe, the owner of the Auburn concrete plant, agreed to pay for LePage’s first year at Husson, but LePage was left to take out loans to cover the rest. Tuition was about $5,000 a year then, and LePage worked feverishly in the summer to make enough to pay the bills.

With less than a week before graduation in 1971, LePage still had a $900 bill to pay before he would be allowed to march at commencement.

“I couldn’t come up with the money,” he said. On a Thursday, two days before the ceremony, the dean of student affairs – one of the administrators who had helped look out for LePage – had a surprise for him.

“They said you’ve done so much for the college that we’re going to write it off,” he said.

“And I graduated,” LePage said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.