Mike LaVecchia likes his wooden surfboard because it’s a little heavier, and therefore a little faster, than conventional foam boards.

And he likes the fact that wood is a renewable resource, so his passion for surfing is not contributing to the overabundance of non-degradable stuff in landfills.

He also appreciates – embraces, really – his wooden surfboard’s coolness factor.

“It’s this thing on your (car) roof you can be proud of,” said LaVecchia, 46, of York. “You pull up (to the beach) and everyone asks about it.”

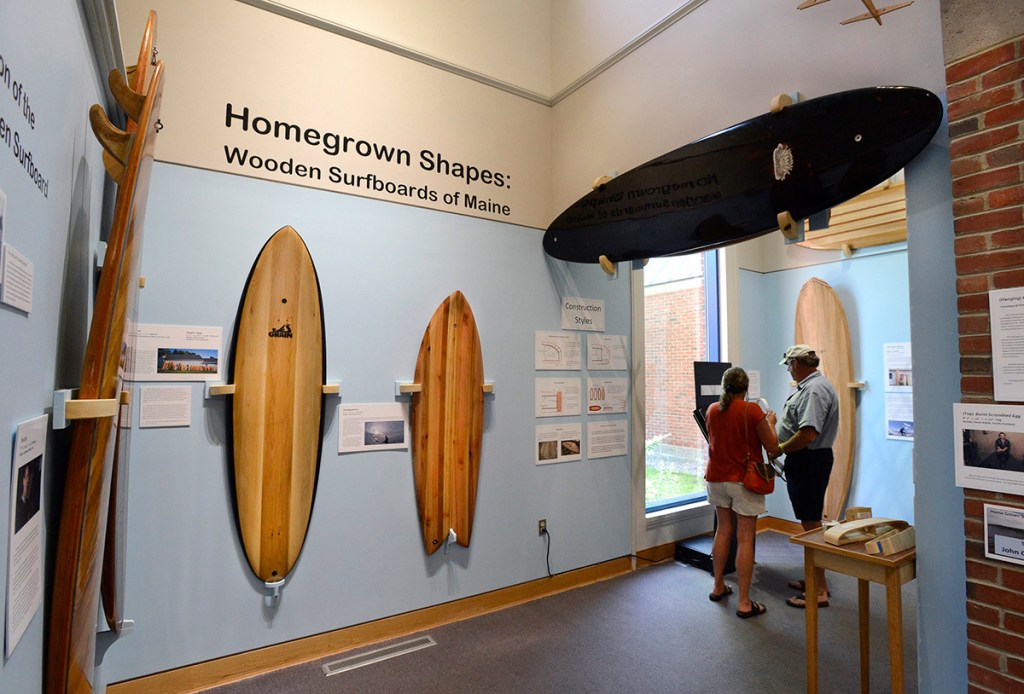

Part of the curiosity factor of wooden surfboards is their relative rarity. Foam boards are cheaper, lighter and mass-produced, so they are what most surfers use. But the Maine Maritime Museum in Bath has managed to find nine Maine wooden surfboard builders who are part of a small but growing trend, for its current exhibit, “Home Grown Shapes: Wooden Surfboards of Maine.”

The exhibit, which focuses on 10 hollow wooden surfboards built over the last decade or so, is on view through Sept. 28. It gives an overview of surfboard history, while spotlighting the art and craft of Maine woodworkers who are putting a modern spin on an ancient mode of conveyance.

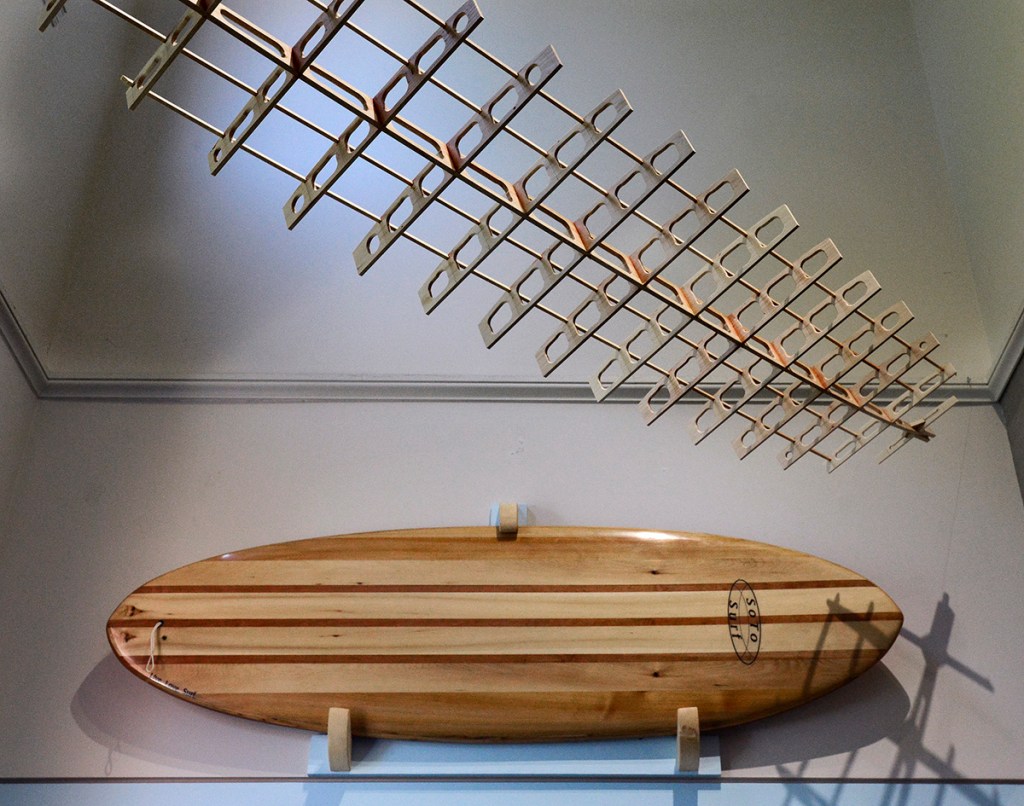

With wood grains visible and certain inlaid designs, the boards on display look more like the tops of Scandinavian coffee tables than sporting equipment. Mostly made of lightweight Maine cedar and sheathed in a fiberglass fabric, the boards are only slightly heavier than foam boards, weighing between 10 and 30 pounds.

But because of the woodworking skill and 20 to 30 hours of labor involved, a new wooden board costs $1,500 to $2,000, compared to the $600 to $900 range for new foam boards.

“They look beautiful, they really have the craftsmanship of a piece of furniture,” said Kurt Spiridakis, 34, boat shop manager at the museum, who organized the exhibit. “Most of these guys have woodworking or boat-building experience. Surfing began with wooden boards, that’s how it evolved.”

Surfboard scholars date surfboards to about 2000 B.C. The Polynesians, who settled the Hawaiian Islands, were early surf riders. The modern era of recreational surfing began in the early 1900s, and surfers used solid wooden boards often weighing more than 200 pounds, said Spiridakis, who did extensive research for the exhibit.

By the 1920s, surfing was popular in southern California. Tom Blake, a competitive swimmer from Wisconsin, became fascinated with paddleboards and surfboards while in Hawaii. He developed the first hollow boards by cutting wooden surfboards in half and carving out hollow chambers. The exhibit features a copy of a 1937 Popular Mechanics article explaining how to make your own surfboard following Blake’s methods.

Hollow boards helped the sport grow rapidly. But by the early 1960s polyurethane foam had become the basic component of surfboards, making them lighter and cheaper. Hollow wooden boards soon disappeared.

Spiridakis credits LaVecchia, a co-owner of Grain Surfboards in York, with helping to bring renewed attention to hollow wooden surfboards. He had boat-building experience, and his company’s first board, named Eve, was constructed a lot like a wooden boat. Grain Surfboards has been in business since 2005.

Eve, which is on display as part of Maine Maritime Museum’s exhibit, includes bronze screws, deck sealant and marine varnish. Most wooden surfboards have a thin, internal wooden frame with outer pieces cut in surfboard shapes and glued together. One of Grain’s internal wooden frames is on display at the exhibit as well.

LaVecchia said modern woodworking tools certainly help when carving and constructing the delicate shapes of surfboards. Most wooden surfboard builders design their boards using computer software. But, LaVecchia said, a lot of the work is old-fashioned.

“There’s a lot of gluing and clamping,” said LaVecchia, who had been a boat builder on Lake Champlain in Vermont before moving to Maine so he could surf more.

The exhibit features a range of surfboard construction methods and looks. Charlie Taylor, who learned woodworking in his father’s carpentry business in York, makes some chambered boards, like the ones Blake created in the 1920s. He cuts a solid board in half, removes much of the interior wood and glues it back together. One of his boards on display at the exhibit, called Earl, is a 10-foot, 6-inch olo-style board made of Asian paulownia wood. Olo boards, native to Hawaii, were the boards Blake based his early designs on.

Taylor, 25, said he designs and builds many of his boards using 14 separate component parts. He works with his father making patio furniture, but also sells surfboards and surfboard kits. He surfed all through college, at the University of New England in Biddeford, and decided to try building surfboards because he had the tools and lots of scrap wood.

“I knew it could be done, so I just tried it and got hooked on it,” he said.

Luke Cushman, who has two surfboards in the exhibit, had geography working against his chances of becoming a surfer. He grew up in Old Town, more than a couple hours from the beaches of southern Maine.

Cushman works as a carpenter out of Old Town but does a lot of work on homes on Mount Desert Island.

He never really surfed until a couple years ago when he and his family spent two months on the West Coast. He and his son Jonah, 11 at the time, fell in love with surfing. His son put the idea of building wooden surfboards in Cushman’s head. So he did some online research and began building.

He’s built about 15 boards and has 10 more in production, with each selling for more than $1,200. Both the boards he has on display are 7-foot-10-inch funboard-style boards, which fall into the medium-size range.

Like most wooden board makers, Cushman, 33, likes that his boards are environmentally friendly. He also likes that they are a little heavier, have more momentum, and so are faster. He notes that “big wave surfers” put extra lead weight on their foam boards, so particularly strong waves won’t rattle the board under their feet.

“There’s so much satisfaction in building them,” said LaVecchia, of Grain Surfboards. “It just makes the whole experience better.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.