The members of American Legion Post 56 in York feel that they were abused twice: once by the con man who ripped them off for $50,000 and once by the legal system they say let the con man off easy.

He ended up sentenced to five years, with all but six months suspended, and is being allowed to pay back the $50,000 in small monthly checks over almost three decades.

But if you think they’re frustrated, talk to the state’s district attorneys, who prosecute thieves, scammers, vandals and other offenders and help arrange for felons to serve reduced sentences in return for a guilty pleas and restitution to the victims.

But when they try to collect the money, the DA’s get just as exasperated as the Legion members, multiplied by hundreds of cases.

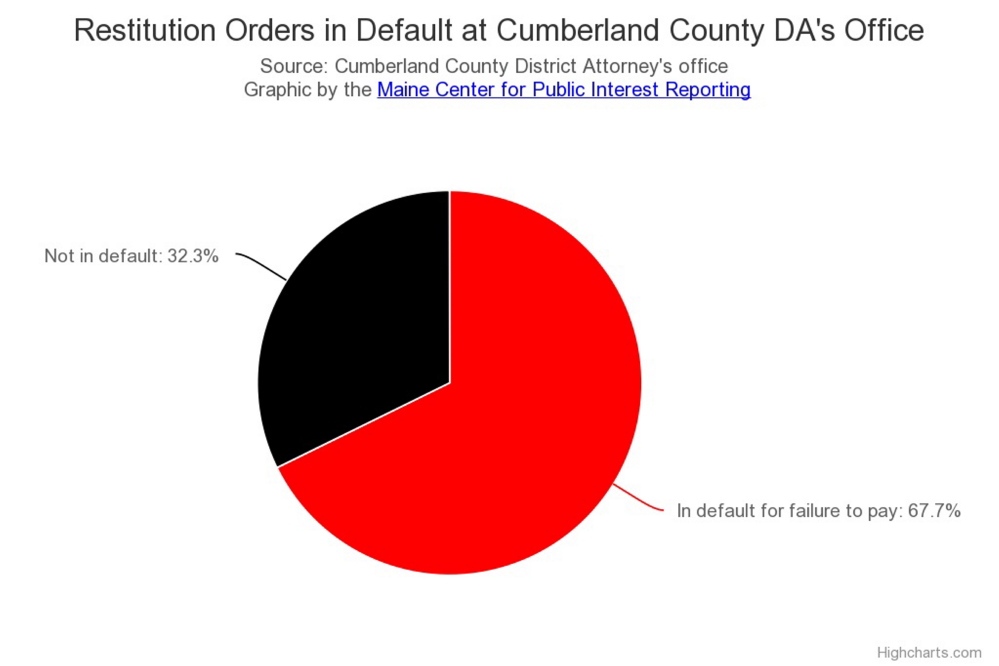

Stephanie Anderson is the district attorney in Maine’s most populous county, Cumberland. About 800 of the 1,181 restitution cases she’s handling are in default.

Speaking about defendants, she said: “They’ll agree to it, and they’ll say, ‘Yeah, I can pay that back.’ Then they get reduced jail time, they get out of jail and don’t pay it back.”

Kathryn Slattery, district attorney for York County, said collecting restitution is “a cumbersome process” involving a lot of paperwork and court actions. “If we don’t have the money right on the table, we have to chase people,” she said.

For victims, “what’s taken from them quickly is paid back over a long period of time,” she said.

District Attorney Carletta Bassano, who covers Washington and Hancock counties, calls the failure of the restitution law a “fundamental reality.”

The reasons are varied, including what prosecutors, judges and defense attorneys call “judgment-proof” defendants who lack jobs or assets to pay restitution they agree to.

“Many of them are indigent, many are hopeful they will become employed or that they will have the resources from one source or another to be able to pay,” said Charles LaVerdiere, chief judge for Maine’s District Courts. “But the reality is, for an extremely large percentage of people, they just don’t have the ability to repay the restitution as promised.”

Then there are those who could pay restitution but don’t, said Geoffrey Rushlau, district attorney for Sagadahoc, Waldo, Lincoln and Knox counties. “Some people just think of it as another bill: They’ll get to it when they get to it.”

Anderson cited a broader reason: “Enforcement is totally lacking.”

It’s very frustrating, because the victim actually has a reasonable expectation that they’re going to get this money,” she said. The victim’s reaction is, “Oh jeeze, the judge ordered them to pay,” Anderson said, but it’s rare the victim will ever see that money.

A Maine Center for Public Interest Reporting investigation found that the state’s system for collecting and enforcing criminal restitution promises victims justice that it can’t deliver. Maine crime victims are waiting for millions of dollars – perhaps as much as $12 million – in payments ordered by the courts from the people who stole their money, broke into their car or burglarized their home.

The exact amount cannot be determined because the state has no centralized system for keeping track of what’s been collected, what’s past due and what’s being done to enforce the court-ordered restitution.

The system for enforcing restitution is not so much a system as it is an uncoordinated series of handoffs among district attorneys, county jailers and the Department of Corrections. All that is complicated by the lack of reliable data, limited judicial resources and weak enforcement tools for prosecutors.

“What you have are all systems that don’t talk to each other,” said Jody Breton, the department’s associate commissioner.

The lottery factor

A weak link in the restitution chain can occur when the plea agreement is struck for the amount of restitution and if the defendant gets probation or jail time.

“Be reasonable,” said Cumberland County DA Anderson, “and don’t get a restitution order for a reduced sentence if the restitution is only going to come if they win the lottery.”

Maine law says courts have to consider an offender’s ability to pay. But some district attorneys said too often the only justification for a restitution order is the court’s thin hope that the criminal might someday pay it back.

Legally, if a defendant in Maine says he has the ability to pay back restitution, the court must take him at his word, said Judge LaVerdiere, citing the criminal code and past judicial decisions. There is no financial screening process.

“It is correct to say that there are times when we know the defendant is not going to pay,” said Maeghan Maloney, district attorney for Kennebec and Somerset counties. “We all look at the defendant and we know that, unless something truly dramatic happens in that person’s life, that person is never going to be able to pay the amount that is owed.”

The courts order the restitution anyway because “it’s the amount that should be paid, that was stolen from victims” as proven through receipts and other documentation, she said.

Meanwhile, the only way for an offender to get out of restitution is to prove it would be an “excessive financial hardship” based on factors like the offender’s dependents and “potential future earnings capacity,” according to a 1997 Maine Supreme Judicial Court decision and statute.

But, counters criminal defense attorney Walter McKee, it often just comes down to whether or not the offender is “able-bodied.”

At the time of ordering restitution, courts can issue an income withholding order – but only if the offender is employed, not going to jail or not getting probation. Probation officers can also ask courts to issue such orders for offenders.

The district attorneys said getting restitution up front – before the defendant gets a deal – is the most reliable way of collecting it.

“Chances are, once we’ve honored our commitments (for a lesser sentence) under our agreement, we’re not going to get” the restitution, Cumberland DA Anderson said. “A small amount should be obtained up front.”

Anderson recalled the time a woman accused of stealing $75,000 from her employer came into her office crying.

“I said, ‘I’m going to indict you for a felony unless you get the money up front,'” Anderson said. “‘Go to a bank, go to a family member, whatever you need to do…’ She came up with the money. Where’d she get it? Relatives, I don’t know … When people have an incentive to get the money, it’s miraculous.”

Others, like York County DA Slattery, said the main issue is the weak enforcement.

“We have to acknowledge that the system is not very good at collecting restitution once it’s imposed, especially if they’re not on probation,” Slattery said

The 25-plus years for the Legion victims to get restitution is not unheard of. One case handled by Bassano’s office calls for monthly payments of $25 – for the next 400 years.

Who’s responsible?

Once the plea deal is approved by the court and the total amount of restitution is established, who is responsible for making sure the money is collected and paid to the victim?

It could be any of three governmental entities: the Department of Corrections, county jails or district attorneys, depending on the status of the felon.

It’s a system of uncoordinated moving parts and gaps in enforcement. Offenders can go from one entity to another, paying – or not paying – without any way for anyone else to know how much has been paid or if it ever gets paid off.

If the felon goes to state prison and/or gets probation, he – and his restitution agreement – are overseen by the Department of Corrections.

The department has a centralized data system that tracks those payments and, as required by state law, automatically takes 25 percent off whatever money a state inmate earns and receives, said associate commissioner Breton.

For those on probation, a probation officer has authority to set the payment schedule if the court hasn’t already done so.

But, said DAs like Rushlau, when a probation officer sets a payment schedule with an offender, that schedule can create a headache for prosecutors. As it is based on the offender’s ability to pay, it can come at odds with deadlines set by courts – the amounts paid can be small and over a longer period of time.

“Some of those numbers are pretty modest,” said Rushlau of the state’s guidelines.

The minimum monthly payment is $25 or four to 10 percent of income under those guidelines. The average monthly restitution payment in Maine is $50, according to a DOC newsletter, but no state data exist for the average time it takes to pay off the full restitution.

While the DOC tracks all offenders while they’re in state prison or on probation, no one ever knows if others pay back what they owe.

“When we at the Department of Corrections get the inmate, we know how much we’ve collected,” Breton said. “But until all the systems talk to each other – all the DAs, county jails and all the courts – you don’t get a good unified picture of it. And that’s been part of the challenge.”

For those who get out of jail without probation, who finish probation or who get restitution without probation or jail time, restitution collection falls to the district attorney.

“The question is always, do you just give up?” said Norman Croteau, the district attorney for Androscoggin, Franklin and Oxford counties. “You can’t give up. There are victims out there that are owed restitution. You really have the obligation to keep going after it as long as you have to. It’s very frustrating, for everybody.”

If the offender has gone through jail and probation, years could have gone by since the sentencing, said Croteau.

“As a victim, you’re wondering, what happened? Am I ever going to get paid?” he said.

A 2011 change in Maine statute made prosecuting attorneys responsible for enforcing restitution from former inmates of state prison and probationers who failed to pay. When an inmate leaves state prison, the DOC must provide “written notice” of how much restitution is outstanding to the courts.

But, Breton explained, when it comes to county inmates, the lack of centralized data means “the district attorney doesn’t know whether or not they’ve paid, or how much has been collected.” County jails inconsistently follow the law requiring inmates to have 25 percent taken off their accounts for restitution, noted a 2009 annual report by the DOC’s victim focus group.

To make it easier for offenders who can’t make payments under the schedule previously set by courts or probation officers, Maine statute lets courts “reduce the amount of each installment or to allow additional time for payment or service.”

But, said Slattery, defendants “are not even under oath when answering questions from the judge about their ability to pay. There’s no investigation of those claims.”

District attorneys say they don’t track every restitution order, partly due to staff funding problems and the lack of an electronic system that flags who’s late on payments.

“There’s not a lot of daily contact, or any real way of supervising them while they have obligations,” said Aroostook County District Attorney Todd Collins.

In Aroostook County, one person handles restitution part-time using the “time-consuming process” of an electronic spreadsheet.

In Penobscot and Piscataquis counties, District Attorney R. Christopher Almy said, “The person here who’s assigned to collection has other duties, and it’s taxing.”

In some offices in Knox, Lincoln, Sagadahoc and Waldo County, administrators are assigned to do collections, while in others victim advocates “do it all themselves, which can be a lot of work,” said Rushlau.

Statewide, victim advocates are also assigned to help victims detail their losses for impact statements used in determining restitution.

York County has one person assigned to restitution. “That’s enormous, and she does a phenomenal job notifying people,” Slattery said. “If she missed somebody, it’s due to being overwhelmed.”

There is no staff solely focused on restitution in Washington and Hancock counties, said DA Bassano.

Bassano said it’s “essential” that her office track restitution cases and work with defendants to get them to pay, because that’s better than “clogging up the court system with every $25 delinquency.”

But working with offenders who leave probation without paying restitution puts DAs “in a very difficult position” legally, said Anderson.

Croteau said the “only enforcement tool” for prosecutors is to file motions to bring the defendant back into court.

At that point, said Rushlau, the district attorney’s “enforcement mechanisms are a whole lot less effective than probation officers, who have the more serious potential violation for nonpayment.” This can result in a revocation of probation when restitution is a condition of probation.

“We have the potential for contempt, which is not anywhere near as effective,” he said.

It’s a method that takes lots of time and “hand-holding,” said Collins.

“We say, ‘That’s great, now we’re going to schedule your next hearing date and make sure you make the next payment,'” said Collins, who hired an accountant 12 hours a month to do bookkeeping that includes restitution records.

Rushlau said his office has “been struggling” to come up with software to track complicated restitution orders that can have multiple co-defendants, crimes and victims.

The vague restitution information the DOC sometimes receives from courts can also create a problem, said Breton. For example she said, court restitution orders can say an offender owes “up to” a certain amount.

“If the order comes to us right from the courthouse, and says clearly what they owe and who they owe it to, we can do that,” she said. “Sometimes it’s up to discretion, and you never know where the line is.”

Even when victims get restitution from inmates, the checks are tiny and can add insult to injury, said Croteau. “Generally speaking, with the amount of restitution owed for many folks, that’s not going to pay the full bill.”

Probation officers receive some training in restitution and determine payment schedules using a departmental form and state payment guidelines – without verifying what probationers claim on the form.

According to state law, the offender is compliant as long as he makes restitution payments satisfactory to the probation officer – who can only ask the prosecuting attorney to file a motion to revoke probation after 90 days of unexcused, missed payments.

“It can take many years in order for an offender to pay their obligation in full, and it takes dedicated probation officers to keep, track and address missed or non-payments,” according to a DOC newsletter.

Mary Farrar, who worked with crime victims for 21 years through positions at the Somerset County District Attorney’s Office, the DOC and Attorney’s General office, said that restitution was not “a priority all the time” for the understaffed probation department.

Probation officers “were not going to chase someone or haul them in if they’ve owed restitution in the past,” she said. “There’s not a lot of them, which is not their fault. They go by the level of violence, this one person may be more violent than the other, so that person is more monitored than another who owes restitution.”

Giving probation officers the discretion to work with offenders in setting payments is better for victims awaiting restitution, said Breton.

“We try not to revoke [probation] strictly based on one criteria, like you missed a payment,” said Breton. “We know that when you immediately revoke (probation), then they’re not going to be paying anything. They might be sitting in county jail.”

‘Throwing up their hands’

Sometimes offenders will be placed in custody or in jail if it can be proved they have an ability to pay but refuse to do so, said Judge LaVerdiere. Maine statute allows courts to confine people who default on their restitution for up to six months or one day for every $5 of unpaid restitution – whichever is shorter.

“Even then, that’s not going to actually cause money to grow in his pockets,” Maloney said.

Sending someone to jail is a “last-ditch consequence” that is “costly to the state,” said Rushlau.

“You can’t put somebody in jail for being poor,” said Anderson.

Victims can also ask prosecutors to file a motion to enforce restitution payment, but what happens next is ultimately up to prosecutors, and then judges.

Anderson said: “You file a motion, have a person brought in, and when they come in, I keep asking the judge to ask the defendant: ‘Do you smoke cigarettes? Do you have cable television? Do you have a smartphone? Did you get an income tax refund?'”

But, she said, “The question that ends up getting asked is: ‘How much money can you pay?’ You can have $12,000 owed, and say, ‘Well, I can pay $25 a month.’ And most of the time, the judge will go along with that.”

Judge LaVerdiere said it’s the role of the district attorney – not of a judge, who is a neutral party – to investigate an offender’s finances.

Anderson said in her view, the biggest challenges include “not enough judges” and a lack of court resources for financial screening.

For Croteau, the messy part is when exactly courts should determine an offender’s ability to pay restitution.

“If you screen someone as they’re going off to prison for two years, do they have an ability to pay then?” he said. “Probably no. What if they get out? A 25-year-old guy – doesn’t he have the potential to pay for another 30 years?”

On top of the financial cost of thefts and scams, said Croteau, victims can lose things of sentimental value, not to mention their peace of mind in their own home.

“The double whammy is that not only are they never going to be able to see that item again – it might have been pawned, or never recovered – they won’t even get financial restitution for that, for a long period of time,” he said.

Anderson said DAs feel disheartened, too. “I want to throw up my hands over it.”

Croteau adds, “It’s all about coming up with a process, I think, to determine the real ability to pay.”

“It’s difficult. It’s kind of a moving target,” Croteau said. “You hate to give up. You can say this person will never have the ability to pay. But that may not be true. Or, are you holding out false hope for victims?”

Part 3: Victims shovel against the tide

The Maine Center for Public Interest Reporting is a nonpartisan, nonprofit news service based in Augusta. Email: mainecenter@gmail.com. Web: pinetreewatchdog.org.

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.