TOKYO — A new generation of Japanese architects is achieving success by reinterpreting the past.

Unlike their predecessors, who modernized Japan with Western-style edifices, they talk of fluidly defining space with screens, innovatively blending with nature, taking advantage of earthy materials and incorporating natural light, all trademarks of Japanese design.

And their sensibility that speaks to a human-oriented yet innovative everyday life is proving a hit abroad, said Erez Golani Solomon, professor of architecture at Waseda University in Tokyo.

“Food and architecture,” said Solomon, stressing how the two are Japan’s most potent brands. “They are powerful – Japan’s strongest cultural identity.”

Kengo Kuma, one of the star architects, finds he is in demand not only in Japan and in the West, but also in places such as China.

Among the major China projects for Kuma are the recent Xinjin Zhi Museum, whose sloping angles and repeated tile motifs are characteristically Kuma, and the ongoing Yunnan Sales Center, a sprawling complex of shops, housing and a theater, where a wooden lattice decorates the main structure overlooking a pond.

He also designs private homes for affluent Chinese who admire Zen philosophy and want to incorporate that stark aesthetic into their daily lives, he said.

Japanese architecture offers warmth and kindness by being adept in the use of natural light and artisanal craftsmanship, such as bamboo and paper. It is “working together like music,” to create a comfortable and luxurious spot even in a cramped space, the basic principle of a Japanese tea house, Kuma said.

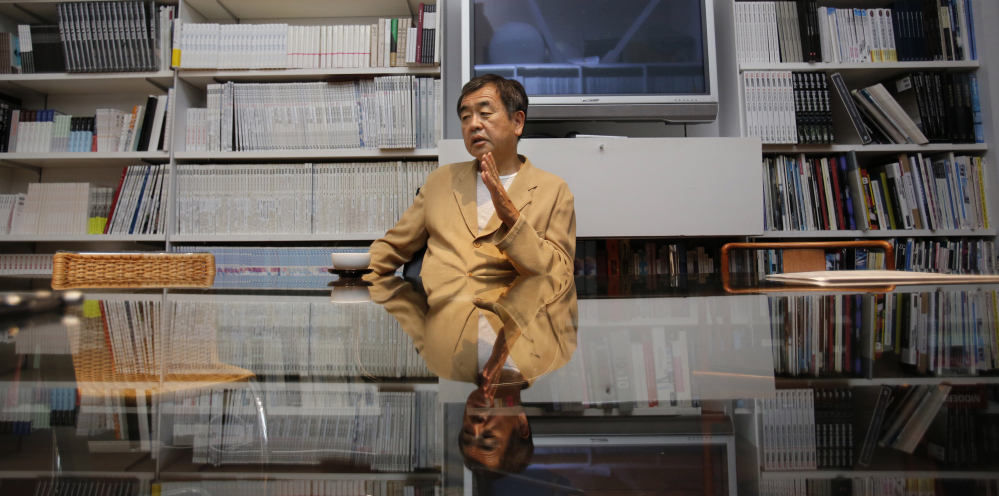

“It’s part of our genetic makeup,” Kuma told The Associated Press, sitting in his Tokyo studio among elegant chairs designed by himself and others by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and pointing with disgust at the vaulting skyscrapers visible from his window.

“People all over the world are sick and tired of modern monuments,” he said. “The desire for the human and the gentle is a backlash to the globalization that brought all these monster skyscrapers.”

Sou Fujimoto, another rising Japanese architect, is also working all over the world.

His beachside cultural center in Serbia is a giant spiral, while a bungalow in southern Japan is a cube of wooden blocks. His Serpentine Pavilion in London of metal lattice has been compared to a floating cloud. In Montpellier, France, construction begins next year for a housing complex he has designed with balconies sprouting precariously at all angles from a tower.

“This understanding of the connection between nature and the man-made is Japanese. The Japanese garden utilizes nature while also being finely crafted. You go back and forth between those two points,” Fujimoto said.

In a telling sign of their rising stature, four of the winners of the prestigious Pritzker Architecture Prize in the past six years have been Japanese: Kazuyo Sejima, Ryue Nishizawa, Toyo Ito and Shigeru Ban.

In the past, the winners were few and far between. Kenzo Tange, known for his statuesque, curvaceous Tokyo Olympic stadium, won the Chicago-based Pritzker in 1987; Fumihiko Maki, who infused an Eastern sensibility into his floating forms of glass, metal and concrete, won in 1993; and in 1996 the self-taught and idiosyncratic Tadao Ando was the third Japanese architect to win.

Sejima, who works with Nishizawa, is coveted for her trademark ethereally white designs, often using glass, such as the Musee Louvre-Lens in France, the Christian Dior building in Tokyo and the Zollverein School in Germany.

Ban, this year’s Pritzker winner, carved out his career by using recycled paper tubes as construction material, and his housing ideas have been widely praised for their use as temporary housing after disasters.

When people were crammed into a gym after the 2011 tsunami in northeastern Japan, his idea of hanging cloth as partitions on paper-tubing frames delivered privacy and a sense of mental peace.

Fuji Kindergarten in Tachikawa, outside Tokyo, by Takaharu and Yui Tezuka, also illustrates the characteristically Japanese idea of fusing the outside with the inside.

The walls of the doughnut-shaped building are glass, and they open as sliding doors into a courtyard. The spherical roof works as a playground for the children to run around and around.

The couple often uses the roof for living space, and they strongly believe that sitting side by side on a sloped surface, like a riverbank, as opposed to facing each other across a table, is good for human relations.

With Japanese architecture, a slight change of approach transforms a roof into something more, in the same way the artistry with which a chef cuts and presents raw fish transforms it into sashimi, Takaharu Tezuka said.

“Some European and American architects say it’s important to have intermediate space, between inside and outside. But our approach is different. Everything is intermediate,” he said.

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.