QUINCY, Mass. — Many decades ago a Scottish immigrant living in the Houghs Neck section of Quincy, who often pedaled his bike to a job at the Fore River shipyard, wrote down stories about an experience he never really wanted to talk about – his years as a soldier in the First World War.

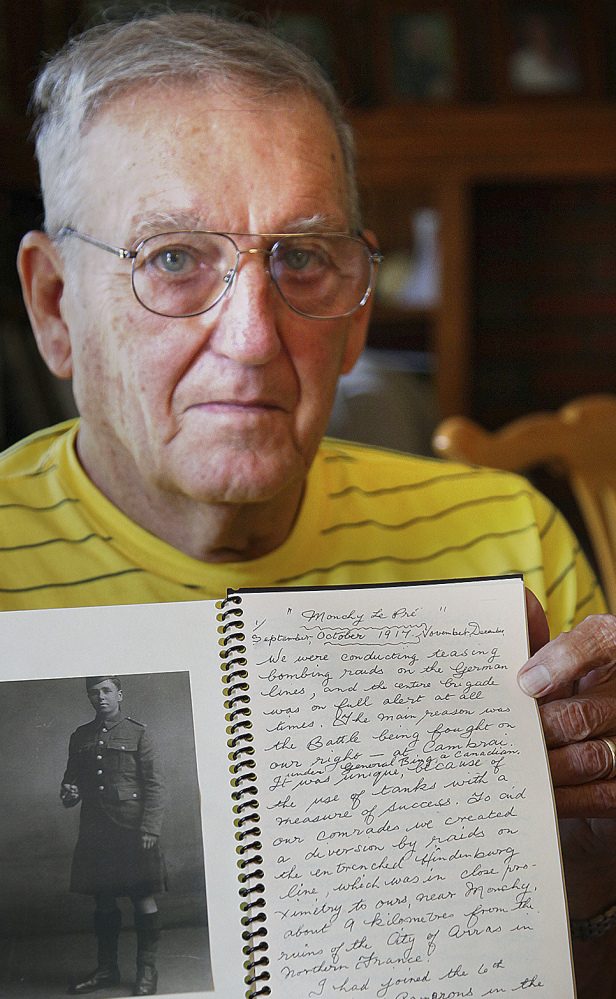

In neat cursive on simple lined paper and a small white notepad, Alexander Scott MacKinlay painted a vivid picture of the trenches scarring the French countryside:

“It, a stagnant deceptive quiet landscape, churned as if a number of fierce giants had handled enormous implements, and left a devastated terrain resembling the aftermath of recurring earthquakes.”

MacKinlay died in 1984, but his son, Alexander Scott MacKinlay Jr., only last year got his hands on his father’s memoir. The papers were left in the Quincy house that his sister inherited.

MacKinlay Jr. can only guess when his father would have written the 90 pages, but he sees them as vital and astounding, not just in their detail but also as a piece of family heritage. Half of the memoir is now bound into a booklet and preserved to teach his children and grandchildren about their ancestor and to let them see through his father’s eyes a war that started exactly 100 years ago.

“I have in my hands an account of one man’s experience in the war, who took time to write about it in graphic form so that the reader could almost live it,” said MacKinlay, Jr., a Rockland resident who was principal of Rockland High School for 35 years.

What makes the memoir’s existence all the more remarkable is that MacKinlay’s father was perennially tight-lipped about his time in the war.

This is what the elder MacKinlay would tell his son if the subject ever came up: “Scott, you don’t want to hear about what I went through. But understand this: There is no glory in war.”

Wounded twice, MacKinlay was also buried alive in a trench that caved in after German shelling and then saved by an anonymous soldier who braved enemy fire to unearth the young Scotsman in the Cameron Highlanders regiment.

“Believe it or not, they fought in kilts and were proud of it,” said MacKinlay Jr.

But pride in their tartans did nothing to ward off the winter in the trenches.

“The effects of the severe cold on the endurance of the men dressed in kilts, and inactive in the confines of the trenches, were cruel to behold,” the war veteran wrote some years later.

MacKinlay, Jr. said he was “blown away” by the fine writing and the storytelling abilities evidenced by his father’s memoir.

“Fires blazed in the dugouts,” wrote the elder MacKinlay, remembering the meals of hot tea with “bully beef stew,” and oatmeal porridge, served “without milk unless you scrounged a can of condensed.”

Bread rations were meager: a single slice with a little jam or cheese.

MacKinlay’s unvarnished account of the First World War doesn’t shy from the injustice and psychological trauma experienced on the front lines.

In one passage, he tells of the moments before being ordered “over the top” of the trenches and into an assault. Rum was doled out to the expectant soldiers, but then a drunken lieutenant turned surly and belligerent with his infantrymen.

“Poking a revolver at our faces, he demanded us ‘to get the hell out of the hole and fight.’ We glared at him in disgust … I was in no mood to take orders from a drunken officer (King’s Rule and Regulation) and stuck my rifle and bayonet under his chin,” he wrote.

Many years later, this war veteran from Scotland would help build Navy ships in Quincy bound for service in the Second World War.

“He made ships to fight Hitler and was very proud,” said MacKinlay Jr.

But the elder MacKinlay’s firsthand experience of combat nearly a century ago carries a tone of pacifism. Recuperating from a battle wound in an English hospital, he was tormented by fears of being sent back to the front.

Nearby was a hospital full of soldiers who had lost limbs, prompting this observation: “This added a deep feeling of compassion, especially if you chanced on a comrade, whom you were acquainted with at other times in robust health … reduced to a wan figure in a wheelchair, another potent indictment of the futility of armed conflict.”

More than 9 million soldiers and 6.8 million civilians died.

“My dad was always very bitter about the carnage and the killing of young men said MacKinlay, Jr. “He felt the men were cannon fodder to irresponsible senior officers who never saw combat.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.