BANGOR – Emma Howard checks the “turf map” on her smart tablet as she heads down Maple Street, part of a quiet neighborhood of older, well-maintained houses and small apartment buildings not far from downtown.

The tablet tells Howard, a 19-year-old paid canvasser for the Maine Democratic Party, a lot about the people behind the doors she will soon be knocking on. Not just where they live but also some personal information, their party registration, turnout for past elections and whether they can be counted on or persuaded to support Democrats in November.

What she learns will be shared back at the party’s nearby field office, where canvassers gather alongside volunteers working a traditional phone bank. Howard’s data will also be fed into a sophisticated database that will be used to shape candidates’ messages, identify political strongholds and weak spots and allow the party to target its efforts effectively.

In effect, Maple Street and other neighborhoods where canvassers go door to door are the places where the 2014 election could be won or lost.

Republicans have their own version of this effort, an initiative called “Freedom 14” that the Maine Republican Party unveiled in June. But Democrats were the first to marry new technologies and aggressive use of social media to traditional “ground game” campaigning. In Maine, the party also has access for the first time to detailed consumer and voting data assembled by the Democratic National Committee.

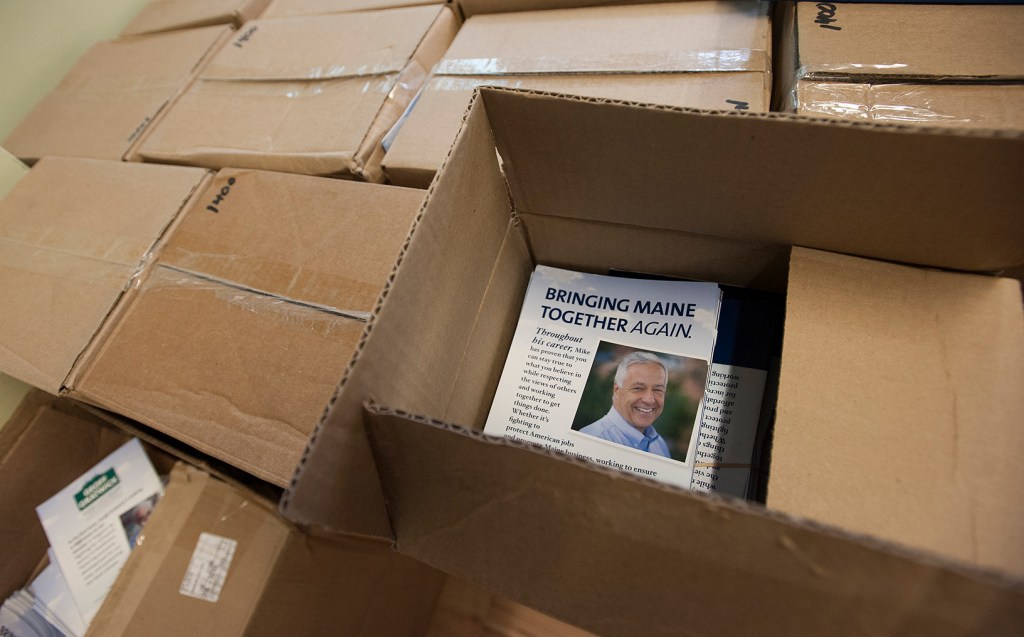

The Maine party is pouring money and people into its street-level operation in its quest to win the Blaine House for U.S. Rep. Mike Michaud, capture both chambers of the Legislature and re-establish Democrats’ former dominance in state politics.

“We’ve already got twice as many staff as we had on Election Day in 2010,” says Jonathan Hillier, the Maine Democratic Party’s field director. “We have about three times as many offices as we had in 2010. We’ve already done the same amount of work that we did in the whole of 2010. Just talking to the electorate, it’s clear that there’s energy. It feels more like a presidential year than an off-election year.”

The Maine operation and others like it around the country are smaller-scale replications of President Obama’s winning campaigns in 2008 and 2012. The basic task is to identify traditional Democratic constituencies, including single women and younger voters, and get them to turn out in a non-presidential election.

It’s a tall order. National polls show that the president is unpopular, although less so in Maine than elsewhere. History reveals that Republican voters tend to turn out in higher numbers during congressional elections, particularly when a Democrat occupies the White House. Polls by the Pew Research Center suggest that Democrats are facing an enthusiasm gap similar to the one that contributed to the 2010 Republican wave election.

These are the challenges that face the Democratic canvassers and their supervisors in the Bangor field office, a room festooned with campaign signs and strewn with boxes, cords and mismatched chairs. But the visual chaos is belied by the sophistication of an operation and a division of duties overseen by Hillier and his deputy field director, Maria Woodbury.

Before the canvassers hit Maple Street and other key streets, Hillier and Woodbury briefed them about that day’s national and state political events, so they can convey information and respond to questions or reactions from residents.

Woodbury then asked the canvassers what they’re hearing at the doors. The team may be a voice of persuasion in the field, but it’s also the eyes and ears of the party, gathering feedback from potential voters about which issues and messages are resonating, which are not and other percolating matters that could create problems for the candidates.

Hillier said the canvassers are trained to stress conversations over the hard sell. Listening more than talking, he said, has allowed the party to sort through its “platter of messaging.”

“We were able to eliminate the things that didn’t work and keep the things that did,” he said. “With our database it’s very easy to take a week or month worth of results and figure out what was working and what wasn’t.”

Party officials won’t discuss which issues are having an impact, fearing a Republican counteroffensive. However, the refined voter file and database also allows the canvassers to test issues and messages, while also locating specific individuals who might be receptive.

The database incorporates information from the state of Maine’s Central Voter Registration database, which is not considered a public record but can be purchased by political organizations engaged in voter turnout activities.

The party is also tapping into Democratic National Committee data, which is being used in selected states, including Kansas and Arkansas, where critical November victories could be attained if voter turnout operations are effective.

“We don’t want to talk to people we can’t persuade and we don’t want to talk to people who are absolutely, definitely coming out to vote for a candidate,” Hillier said. “It allows us to concentrate on the sector of the electorate that’s going to have the most impact.”

For Hillier, generating high turnout is the sole purpose of the operation. Not only are the canvassers trying to activate natural constituencies, but they’re also integrating their data with face-to-face conversations to identify and register new Democratic voters.

The potential new voters are dubbed “persuasions” by members of the field team, which assign scores after each contact and upload the information to a database. The idea is to continually refine the message and interact with persuadable voters until the canvassers are confident they will vote Democrat.

That’s the task facing Howard on Maple Street, where she raps on Joe Fisher’s door. Fisher, 57, voted for Eliot Cutler in 2010, and his wife voted for Gov. Paul LePage.

Howard shows Fisher the latest poll commissioned by the Michaud campaign.

“It’s still a close race, but Congressman Michaud has the best chance to win,” Howard says. “The only thing Cutler can do at this point is help re-elect Gov. LePage.”

Howard asks whom Fisher would vote for if the election were held that day. He gives the desired answer – Michaud – and then, unprompted, begins to explain why.

“I’ve seen a lot of politicians come and go, but I’ve always liked Mike,” Fisher says. “He seems to be for the working man.”

Fisher’s answers about other Democratic candidates indicate Howard and the party have more work to do. He likes Democratic U.S. Senate candidate Shenna Bellows but believes Republican Susan Collins has served Maine well. He’s not completely sure he’ll vote for Democratic 2nd District candidate Emily Cain, but he associates Republican Bruce Poliquin with “negative politics.” He doesn’t know a lot about the legislative candidates.

That disappoints Howard, who says later that she wishes she’d done more to talk to Fisher about the other Democrats running for the State House.

Republicans are running their own version of the ground game to support the LePage re-election campaign. But party officials wouldn’t give details about the operation and funding, so it’s unclear to what extent their effort relies on paid canvassers, traditional phone banks or some combination of tactics.

However, the party has opened seven field offices and it has a significant well of money to draw from, thanks to the Republican Governors Association, which spent $1 million here in 2010, some of which paid for a grass-roots campaign widely credited with helping LePage win.

Democrats also won’t specify how much they’re spending on the ground game, but they have a major cash stockpile to support the operations. The party’s national committee has already dispersed more than $852,000 to Maine, considerably more than the $574,000 spent by the Republican national and state committees. Democrats have also racked up some valuable interest-group donations, including a $300,000 contribution from the United Steelworkers Union in February, a time when field operations were being set up. Ben Grant, state party chairman, said Democrats are attracting big donors because Maine’s gubernatorial race has attained a national profile.

“It’s a major pickup opportunity for Democrats,” Grant said.

Cutler, the independent candidate for the Blaine House, had hoped to beef up his ground operation after he finished less than 2 percentage points behind LePage in 2010. The campaign has acknowledged that the absence of a door-to-door operation may have prevented Cutler from winning.

The campaign suffered a setback this year when its field director, Brandon Maheu, abruptly departed in February. Cutler’s campaign has said that it’s still committed to a field operation; however, expenditure reports show that much of its money has gone to other activities, including fundraising and television ads that Cutler also needs to remain competitive.

The stakes are high in the ground game for all of the candidates.

It’s widely accepted that successful turnout operations can be worth 2 or more percentage points on Election Day. The University of New Hampshire Survey Center, in a poll for the Maine Sunday Telegram in mid-June, found Michaud with a narrow lead over LePage, 40 percent to 36 percent, within the poll’s margin of error. Cutler was in third place, with 15 percent of the vote.

Democrats hope their ground game will tip the scales in what is expected to be a low-turnout election. In fact, party leaders are counting on it.

“If it is close, we’ll be able to take (Michaud) over the finish line with this operation,” said Grant, the party chairman. “I believe that deep down, and that’s why we’re doing it.”

It’s a task laden with failures and long nights for canvassers like Howard, who will log hundreds of hours, if not more, walking sidewalks and knocking on doors.

Some people she encounters are receptive. Others are not. During her canvass on Maple Street, one woman told her she was too busy to talk about the election, another shouted through her screen door that nobody in her family would vote for Michaud.

Yet another woman, not a scheduled stop on Howard’s “turf map,” spent 10 minutes ranting about unscrupulous contractors who had run up the bill on her house renovation.

Each of the paid Democratic canvassers makes $10.10 an hour – a nod to the minimum wage increase proposal that national Democrats hope will activate core constituencies such as single women and younger voters. Some of the canvassers are holdovers from the 2012 Maine marriage equality campaign, which deployed a similar operation described simply as “one-on-one conversations.”

The process will continue from now until Election Day as the interactions are scored and entered into a prediction model. At some point, the party’s field team could have the best forecast of who will win on Election Day.

“We tend to trust our numbers more than polls because we talk to more people,” said Hillier, the field director. He said the team is reaching thousands of voters every day between the traditional phone banks and the canvass team.

It’s a long way between now and Election Day. Victory for Michaud and the Democrats is far from certain, as is the impact of the extensive field operation.

But Hillier is confident.

“We’ve got the candidate we wanted. We’ve got the opponent we wanted. We’ve got the resources we want,” Hillier said. “We’ve got the people, which is the most important thing, as far as I’m concerned.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.