Before Election Day, many Mainers received an ominous postcard in the mail that claimed to show whether their friends and neighbors had voted in past elections, and included a veiled threat that they too could be exposed if they didn’t do their civic duty and vote.

The threatening mailers angered some Mainers, but exactly who sent them remains a mystery. It also is a mystery – even to state elections officials – how the group apparently got hold of the state’s confidential voter database, access to which is limited by law.

“It certainly had a pungent odor to it,” said Maine Secretary of State Matt Dunlap, whose office received dozens of complaints about the letter, mostly from registered Republicans, who appear to be the primary recipients. “You can tell that whoever did this did not want people to know who they are, and for obvious reasons.”

The tactic used in the mailer, known as social pressuring, has been used in Maine and other states by political organizations trying to drive voters to the polls. However, the threatening language of the mailer, and the opaque nature of the group that sent it, reveal how data about Maine voters is collected, sold and used by all kinds of political organizations, and even by government agencies such as the immigration service.

The mailings also show how political strategists are continually finding new ways to exploit “keyholes” in campaign finance and communications laws in Maine and other states.

No group has accepted responsibility for the mailers circulated in Maine. But an important clue can be found across the continent in Alaska.

Voters in Alaska received a nearly identical letter – right down to the font type, the wording and the logo, which can easily be mistaken for an official state seal. The Alaska letter, however, left a single breadcrumb: a disclaimer from a super political action committee funded primarily by a retired chemical company executive in Oregon who is closely linked to industrialists Charles and David Koch, two of the most prolific funders of the modern conservative movement.

The trail in Alaska, however, ends much as it does in Maine – in the political catacombs of shell companies, nonprofits and limited liability corporations that are designed to hide identities, donors and motives.

The group named on the postcards circulated in Maine, the Maine State Voter Program, has no physical footprint here other than a post office box in Augusta and a website. An entity listed as a parent company, Be Counted Inc., is not registered with the state, according to corporate filings. It is registered as a nonprofit in Ohio, according to corporate filings, but it has no address or phone number. The Columbus, Ohio, attorney who registered the company did not respond to a request for comment.

The group behind the mailers apparently had access to Maine’s Central Voter Registration database containing detailed information about Maine’s voters, including when they voted. While it does include party affiliation, the data does not include how Mainers voted.

It’s a mystery how it got the non-public database. Neither the Maine State Voter Program nor Be Counted Inc. is among the nearly 70 political organizations or candidates that tried to purchase the data from the state since 2012, according to documents obtained through a Freedom of Access Act request by the Maine Sunday Telegram.

And despite voter complaints and criticism by public officials such as Maine’s secretary of state, neither Maine nor Alaska has launched an investigation into the group, or groups, that sent the letters. That’s because nothing about either communication appears to be illegal.

LEGAL SALE OF INFORMATION

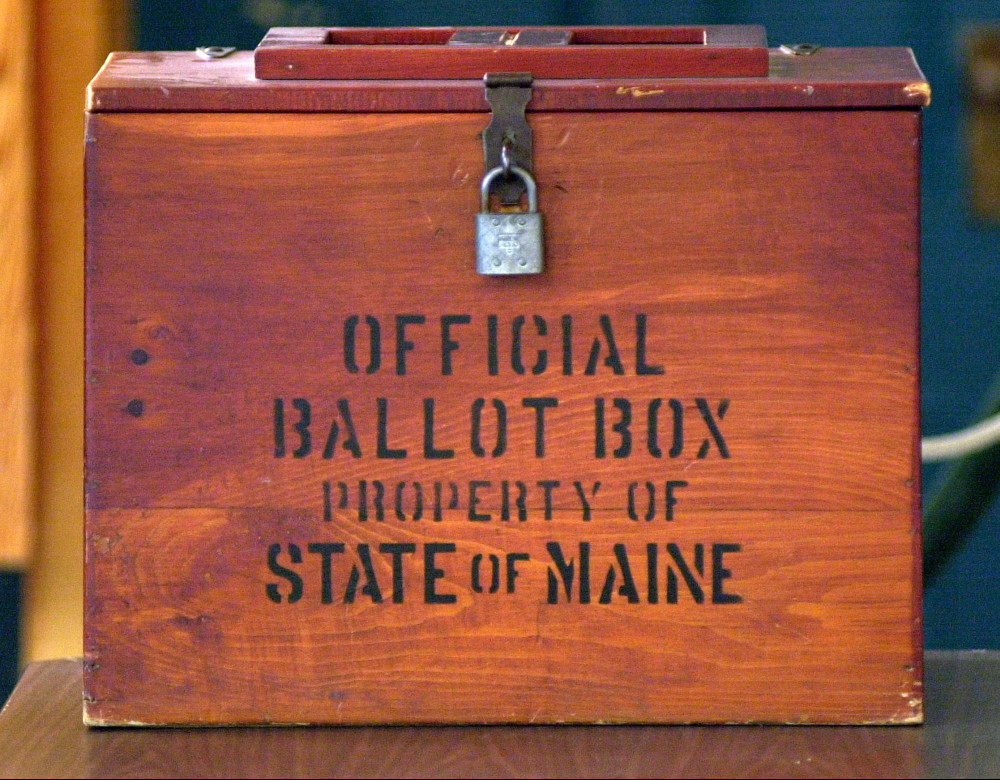

All states now collect and keep a Central Voter Registration database that contains updated information about new voters, changes of address, party affiliation and election participation – the same type of information apparently used by the group behind the mailer.

Maine’s database was created in 2006, a response to the 2002 passage of the Help America Vote Act, a sweeping law that created uniform standards and procedures in all 50 states. Among other things, the law mandated that states create a centralized voter registration database to track changes in the voting population.

Each state sets its own rules about who has access to the database. Some states make it available to the public. Maine decided to make it available only to political groups and government agencies. Dunlap said lawmakers exempted the database from the state’s open records law in part to protect Mainers’ voting data from being used by commercial entities.

Political organizations and candidates can purchase the Maine’s Central Voter Registration database for $2,200, while smaller data sets, such as for a specific electoral district, can be purchased for less. The cost is designed to cover maintenance of the database, which is routinely updated as new voters are registered and people move.

Prior to the creation of the central database, political organizations had to visit each of the state’s more than 500 municipalities and townships to compile statewide voter registration. In fact, the information about individual voters still resides in city and town halls and is available to the public. Your neighbors can look up your voter participation if they want. The limits on public access apply only to the aggregated database of Maine voters – the form in which it has the most value to political or commercial entities.

Government entities and law enforcement also can – and do – pull information from Maine’s central database.

In July, the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement office in South Portland requested the names, dates of birth and addresses for registered voters in Portland, South Portland, Lewiston, Bangor, Kittery and Biddeford who participated in the 2012 election. John Lenotte, the ICE agent who requested the data, declined to provide information about the investigation or to speak broadly about how voter information would be used.

Some entities that want the data – presumably for commercial purposes – are turned away. The Telegram’s records request reveals that the state has denied several requests from data mining organizations, which sort through data for information that can be sold to other businesses.

Nonetheless, the threatening campaign mailers from the Maine State Voter Program reveal the state’s limited ability to restrict resales of the database or keep track of who gets the data once it leaves the state’s control.

“There are no penalties for redistributing (central voter) data to another group for the purposes of a get-out-the-vote effort, but the data cannot be sold to commercial entities or used for commercial purposes,” Maine Assistant Attorney General Phyllis Gardiner said.

At the same time, state officials acknowledge that their ability to monitor the data sharing is limited.

“The groups that use our information sign an agreement and know the rules,” said Julie Flynn, deputy secretary of state with the Bureau of Corporations, Elections and Commissions. “But the reality is we have no way of ensuring that other groups who obtain the information use it the way the law intends.”

The state also has no way of identifying groups that get the information secondhand and use it legally, but in a way that Mainers find objectionable.

USE OF SOCIAL PRESSURE

John Fahrenbruch, a 50-year-old Sanford resident, was one of many Mainers who received the letter from the Maine State Voter Program.

“Your voting record is a public record,” the letter read. “After the November 4th election, your friends, your neighbors, and other people you know will be able to find out who voted and who did not vote. DO YOUR CIVIC DUTY – VOTE!”

The letter claimed that Fahrenbruch failed to vote in two elections since 2008. However, the registered Republican said he did vote those years, just not in Maine. He lived in Michigan until 2010.

“It definitely felt like an invasion of privacy,” he said. “I felt violated. I prefer to keep my personal information from anybody I can.”

Vera Northrup of Union was equally offended. In a letter to the Maine Sunday Telegram, she wrote that her husband would be “devastated” to know he’d been listed as a non-voter to his neighbors. He voted consistently until Alzheimer’s forced him to seek residential care at The Woodlands, she wrote.

“Most people in the medieval times were put into stockades when they were going to shame someone; today, the stockades are just in the form of letters sent out,” Marc Smith, a Navy veteran from Brunswick, wrote in a letter to the editor published in the Portland Press Herald.

While Mainers and Alaskans both found the letters offensive, the tactic behind the mailers – social pressure – is scientifically tested and frequently used by political campaigns to get out the vote.

In fact, not only is the Maine letter identical to the Alaska letter, both were lifted, nearly word for word, from a sample letter used by two Yale University professors studying the effects of social pressure on voter participation. The study, and examples of the letter, were published in 2008 by the American Political Science Review.

The study found that the effect of social pressure on voter turnout “to be formidable” and “exposing a person’s voting record to his or her neighbors” is more useful than conventional partisan mailings.

The social pressure tactic was widespread during the Maine gubernatorial race. Groups such as America Votes, a Washington, D.C., group of labor unions and progressive organizations, used it to increase Democratic turnout. America Votes has not purchased Maine’s database directly, but it may have received some form of it from an organization like Catalist LLC, a national organization that builds sophisticated voter files by merging state voter registration data with other information, such as which voters put up campaign yard signs. Catalist then provides the enhanced database to progressive and labor organizations for get-out-the-vote efforts.

While other mailers raised eyebrows, the Maine State Voter Program and the identical Alaska mailer made headlines. Recipients claimed there were errors and called the letters an invasion of privacy.

Also, recipients in Maine had no idea who sent them or who paid for them. Dunlap said some residents who complained wrongly believed the state was behind the mailers. Commenters on conservative Web forums suspected Democratic perpetrators trying to intimidate Republican voters.

Jonathan Wayne, executive director of the Maine Commission on Governmental Ethics and Election Practices, which oversees state campaign finance laws, said the mailers could not be investigated because any campaign activity that encourages people to vote but does not refer to a specific candidate or ballot question is exempt from campaign finance disclosure laws.

A CLUE IN ALASKA?

While there was little disclosure information on the mailers in Maine, the Alaska version appears to provide a clue.

There, a small disclaimer showed that the letter was paid for by a super PAC called the Opportunity Alliance, a group primarily funded by Lake Oswego, Oregon, resident John Bryan, a retired executive from Georgia Gulf Corp., a subsidiary of the Koch-owned Georgia Pacific. Federal Election Commission records show that Bryan is a big donor to a number of conservative groups, including the Koch-backed group FreedomWorks.

Bryan could not be reached for comment. However, according to various interviews with Alaskan media, he claimed to have no knowledge of how Opportunity Alliance would spend his money. His primary goal, he said, was to advocate for charter schools.

In one interview with Alaskan Public Media, Bryan referred a reporter to a man named Stuart Jolly, the former Oklahoma director for Americans for Prosperity, another conservative group with a chapter in Maine.

On June 24, Americans for Prosperity in Maine purchased the state’s Central Voter Registration database to update the group’s voter file. However, Carol Weston, the director of the AFP-Maine chapter, said her group has no affiliation with the Maine State Voter Program or Be Counted Inc.

“I did do a get-out-the-vote program, but it had nothing to do with those kinds of letters,” Weston said. “My experience has been that there is a certain point in which you cross the line and you shouldn’t do that, partly because you’re not successful.”

There is no evidence that the same group was operating in both states. Because the Maine law doesn’t require groups to disclose political communications unless they directly support or oppose a candidate, there’s no record of a mailing directed to Maine by the Opportunity Alliance PAC.

Even the PAC’s expenditure reports lead to a dead end. The most recent filings with the Federal Election Commission do show two mail operations, one for $32,000 on Oct. 2, and another for $57,500 on Oct. 14. However, the target of the mailings is not recorded. Also, the consulting firm that produced the mailings, Jopaulsh LLC, is a mystery.

According to the FEC filing, the consulting firm is located in Philadelphia. But an agent for Pennsylvania’s Corporations Division for the Department of State said the company was not registered there.

Jopaulsh LLC is, however, registered in Delaware, with no address or phone number. According to corporate filings, the firm is registered by Corporation Service Co., a company that is hired to register a large number of corporations in Delaware.

The tone of the mailings and lack of information about who sent them should lead to changes, according to some Maine recipients.

Fahrenbruch, the Sanford man who received the mailer, said exposing voter participation this way should be illegal. He’s careful about his privacy.

“I don’t give anyone my Social Security number unless you’re giving me a paycheck,” he said. “I keep a piece of tape over my driver’s license number.”

It’s unlikely that social pressure mailings will ever be outlawed. Also, Dunlap said that most groups that use the Central Voter Registration database don’t abuse it.

However, he indicated that the controversy over the Maine State Voter Program mailer could lead to some changes.

“It’s like any election law,” he said. “If there’s a single keyhole-sized loophole, some political organization will find a way to drive a tractor-trailer truck through it.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.