The Baron of Country Music wrote songs about them. American seamen pelted a sinking enemy submarine with them in World War II. They supply starch for textile sizing, feed for livestock and material for manufacturing biodegradable plastics. But, with prime potato-mashing season upon us, we’re doing what we love to do most with Maine potatoes – cooking them up and chowing them down. Preferably – at least in my book – with lots of Maine butter.

While you’re mashing away, here are a few historical Maine potato gems to liven up your kitchen playlist and your spud story inventory. “Spud,” by the way, is the name of the tool used to uproot potatoes. By 1845 – according to the Oxford English Dictionary – the word had become slang for the potato itself.

Fort Fairfield’s own Dick Curless recorded a number of country hits in the 1960s, but it was two potato-themed songs, “Tater Raisin’ Man,” and “A Tombstone Every Mile” that anchored the Potato Pickers’ Special, a radio show that began broadcasting in 1959 as a way for farmers to let pickers know what time to hit the fields. Program originator Wayne Knight used the honky-tonk inflected “Tater Raisin’ Man” to cue up his 4:30 a.m. eye-opener show:

“I pick ’em up, pick ’em up, put ’em in the barrel / Put the big ol’ barrel on the tater truck / If you’re gonna make money when you’re raisin’ these spuds / Well you sure need a whole lotta luck.”

Once the potato trucks were loaded, they made the trip from Aroostook to Boston markets and other points south, often via Route 2A, which had a treacherous curve known as the Haynesville Woods. “If they buried all the truckers lost in them woods, there’d be a tombstone every mile,” Curless sang.

The potato barrel, by the way, was invented by the Potato Barrel King, also known as Wilbur Horatio Harding. Born in Appleton in 1861, Harding was trained as a cooper, making potato starch barrels in the days when Maine potatoes were more widely used for starch than food, as limited road and rail transport made it difficult to get fresh potatoes to urban markets before they rotted or froze.

When Harding moved to Houlton in the 1890s, he found starch barrels to be excellent containers for fresh potatoes, too (by then the spuds could be moved by rail), except for their size; they were too big for easy handling when fully loaded with potatoes.

Harding developed a smaller barrel that was light enough to be loaded onto a wagon when full, and sturdy enough to last several seasons. The Harding potato barrel was a hit in the booming potato industry, and the full barrel – weighing in at about 165 pounds – became the unit of measure for Maine potato buyers and sellers until just 25 years ago, 1989, when the state converted to a hundredweight measure.

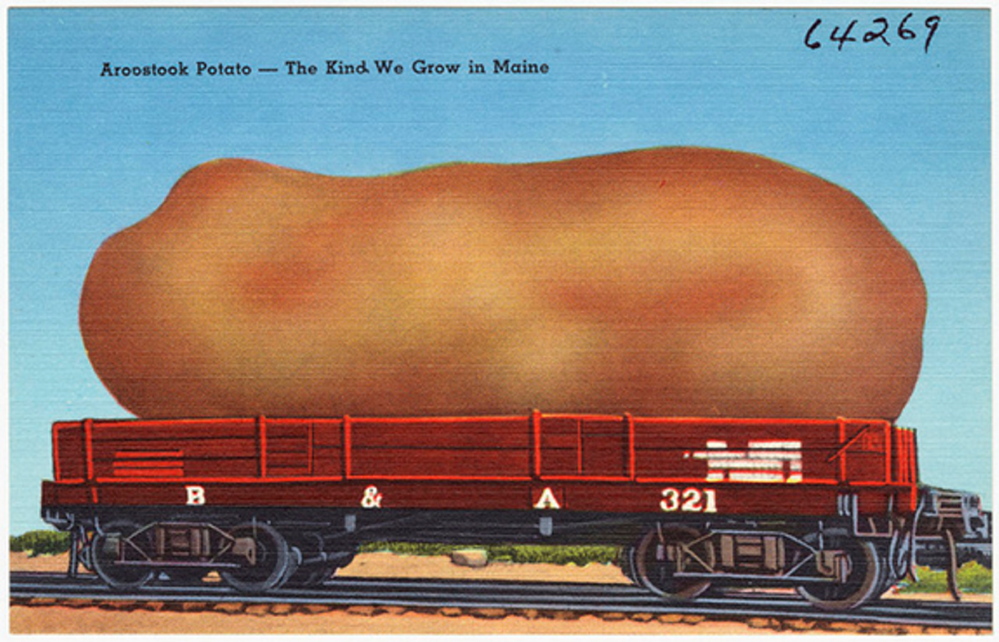

Beginning at the end of the 19th century, the Bangor and Aroostook Railroad was a major factor in getting barrels of fresh Maine potatoes onto dining tables in relatively distant markets such as Boston and New York. Though the trains could deliver quickly, the cars weren’t temperature-controlled in the early 1900s, so the railroad employed “potato caretakers” to monitor heating equipment and ensure that the spuds didn’t freeze.

Perhaps you remember the spud gun – a staple mail-order novelty item in old comic book ads that “shoots harmless potato pellets”? But did you know that during World War II, Maine potatoes were used as ammunition on the Maine-built destroyer USS O’Bannon?

According to James Horan’s history of the O’Bannon, “Action Tonight,” in 1943 the destroyer encountered an enemy submarine in the southwest Pacific. After an initial attack with guns and depth charges, the battle-weary O’Bannon crew, energized by impending victory, proceeded to pelt the crew of the damaged enemy sub with Maine potatoes grabbed from the spud locker. The only person who wasn’t happy about it, according to Horan, was Melvin “Pappy” Rowland, the commissary chief.

While Maine no longer dominates national potato production, spuds remain the state’s biggest vegetable crop. According to the Census of Agriculture, nearly 85 percent of all vegetables harvested in Maine in 2012 were potatoes. And they’re still iconic of Maine food – from chowder to Needhams. I don’t know about you, but I’ll drink to that – with a short, icy shot of Maine potato vodka.

Meg Ragland is a culinary historian who is working on her first book, “Boston: A Food Biography.”

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.