On the first Sunday in June 1722, Edward Low’s pirate crew struck New England. In that single day the pirates captured three vessels, one after another, as they were sailing near Block Island, just off Newport, Rhode Island. Low’s crew of about 40 pirates tore apart the vessels, stripped them of sails and rigging, and hacked at one of the captured captains, James Cahoon, until he was covered with blood and wounds.

But the capture of a Nantucket whaling sloop that day would prove to be the deadliest, marked by the sickening brutality that defined the pirate captain Edward Low. And some of the shocking details from the attack emerge from a surprising source in Portland. Tucked away in the archives of the Maine Historical Society is a fragile, leather-bound diary kept in the early 1700s by the Rev. William Homes, a minister from the village of Chilmark on Martha’s Vineyard. The Homes diary is a bit of a mystery – after all, how did the journal of a minister from Martha’s Vineyard end up in Portland? But the diary also provides an incredibly rare look back at reaction to the vicious pirate attacks that threatened coastal New England 300 years ago.

Most of the vessels captured by Low’s crew that first weekend in June were completely destroyed. One of the sloops was torn apart and left stranded at sea about 10 miles from Block Island. The pirates robbed one of the wealthier passengers who had been aboard that sloop, the adjutant of a militia regiment from New York, taking a sword, a gun, buttons and a number of articles of fine clothing, including a red Persian silk scarf and a beaver hat with silver lace.

But it was Low’s capture of a whaling sloop that had the deadliest repercussions. The pirates took at least six men from the sloop as captives: two white men and four or five Wampanoag Indians, who typically made up a large portion of whaling crews during this period. Low and his men then sailed north. Only days later, however, the pirates hanged two of the Wampanoag men somewhere between Massachusetts and Nova Scotia. Word soon reached Homes on Martha’s Vineyard, who recorded the horrifying scene. A sea captain “sailing from the Eastward,” Homes wrote in his diary, “found the dead body of a man floating upon the water with his head cut off and his hands and feet bound, which act of cruelty is supposed to have been done by the pirates which greatly infest the coast.”

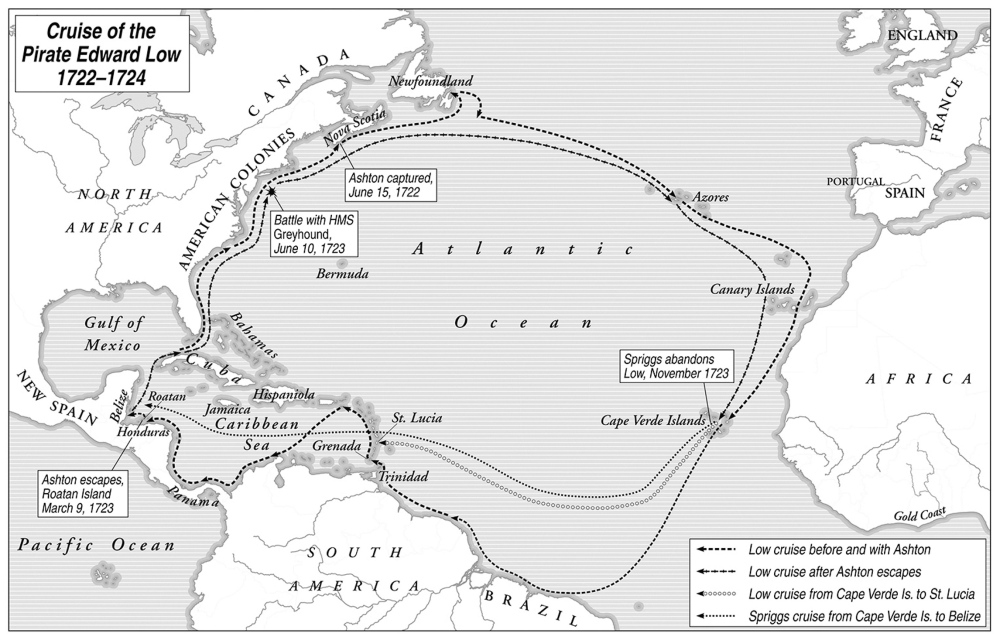

A year later, in June of 1723, Homes also described in his diary the pirate’s bloody encounter with a British warship, the Greyhound, which resulted in the capture of one of Low’s two sloops. That capture – and the execution of 26 convicted pirates a month later – was seen as a major victory in New England since Low was, by now, notorious. “A greater monster,” one Caribbean official wrote of Low, “never infested the seas.”

In his diary, Homes devoted considerable space to the engagement between the Greyhound and the pirates. Because the winds were so light that day, the battle had played out slowly over many hours, the three vessels maneuvering cautiously through the water. At some points the pirates and the Greyhound were as much as three-quarters of a mile apart from each other, but eventually the pirates came within firing range and attacked the warship. “They kept firing,” Homes wrote in his diary, but “without doing him any great damage.”

The Homes’ diary in the Maine Historical Society offers a fascinating window into reaction to pirate attacks in Colonial New England, yet I was puzzled in my research by a curious question – how did this diary end up in Portland? I found the answer in another rare old book, “A Genealogy of the Allen Family,” published in 1882 in Farmington. This book includes a brief sketch of William Homes and his children. Homes lived on Martha’s Vineyard until his death in 1746. His diary was held by his daughter Hannah, who never married and spent her later years living with her sister Jane and brother-in-law Sylvanus Allen. When Hannah Homes died at age 90, the Homes diary was taken by her nephew Zebulon Allen to Farmington around 1822. It was later deposited in the Maine Historical Society, where it remains today.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.