Burton Hatlen was a poet, teacher, mentor to Stephen King and a self-described “public academic” who believed passionately in the power and imagery of language.

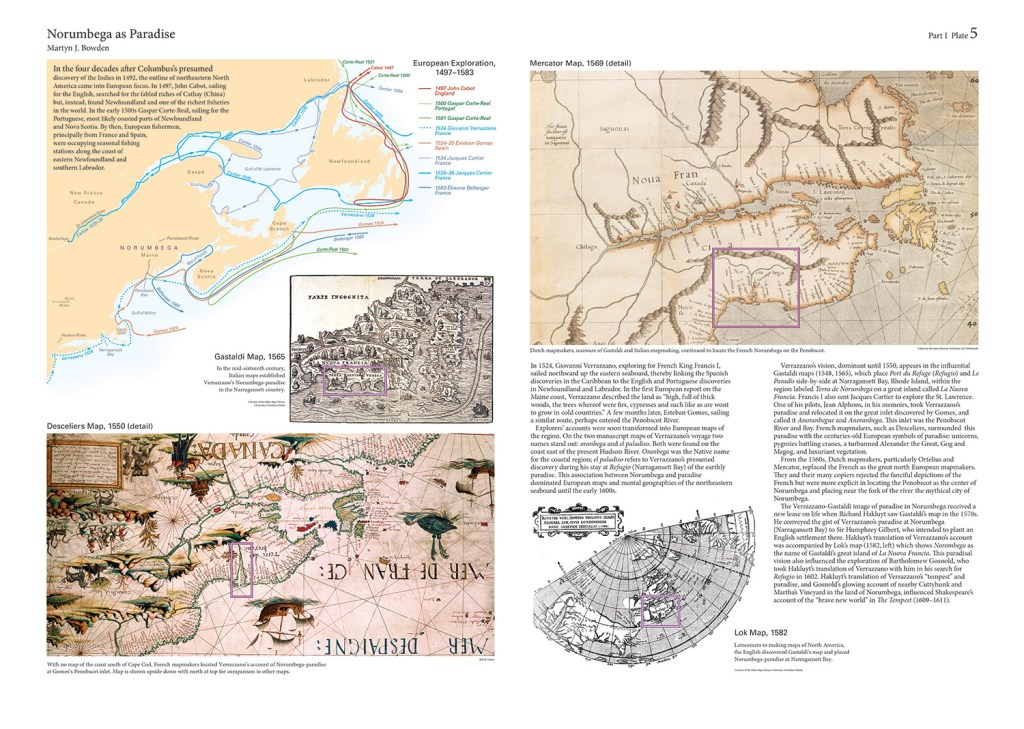

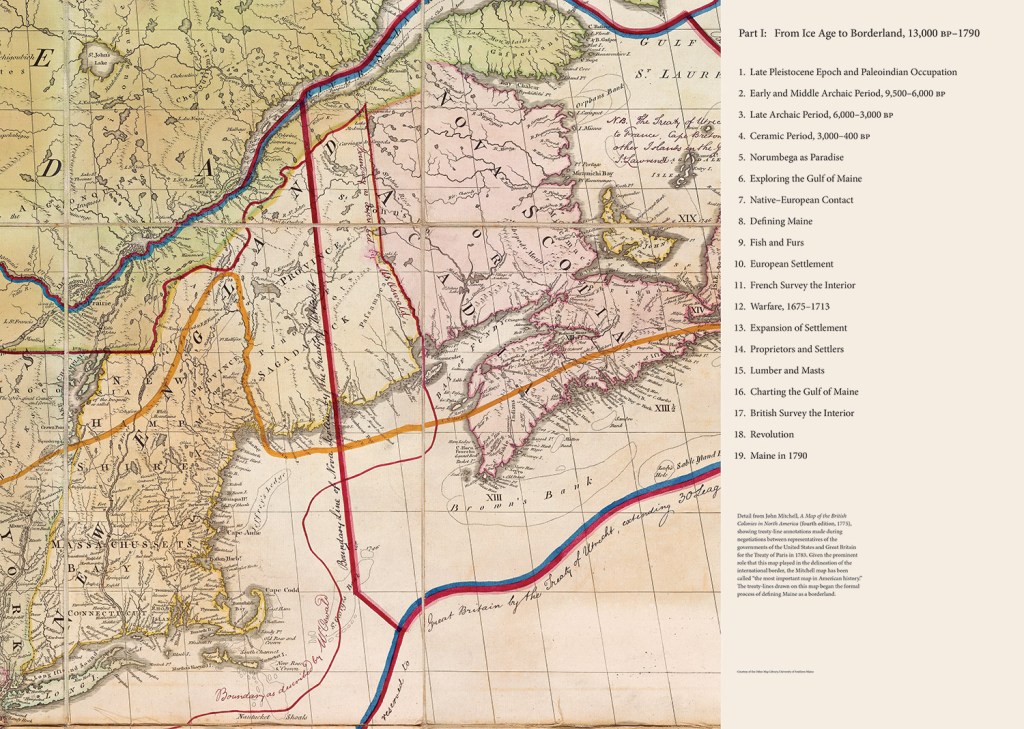

Where others might see the history of Maine from the last ice age to the 21st century as a collection of charts and statistics, Hatlen saw the possibility for a story, of Maine and its people, told with thoughtful words, detailed pictures and beautiful maps. In 1997, with no experience as a historian or cartographer, the English professor proposed to his University of Maine colleagues the idea of creating a comprehensive historical atlas of Maine, covering some 13,000 years of state history.

Hatlen died in 2008, at 71, after a long battle with prostate cancer. But two of his colleagues have spent more than a decade turning his idea into reality. The “Historical Atlas of Maine,” featuring more than 300 specially made maps and published by University of Maine Press, came out this month.

The book’s editors, UMaine professors Stephen J. Hornsby and Richard W. Judd, say the comprehensive work is the first attempt at such a Maine history atlas since the 1970s, and that it’s rare among state atlases for the depth and sophistication of its maps and information.

Hatlen “would have liked (the atlas) very much. It’s such a thorough way to look at the state,” said his wife, former UMaine English professor Virginia Nees-Hatlen. “He did think in terms of story, but he was also very interested in art, in politics, in economics. With the atlas, he saw the potential for an interdisciplinary project that would engage different faculty and be of service to the public.”

Hatlen was co-founder of the National Poetry Foundation and had taught at UMaine since 1967. When he died, King called him “a mentor and a father figure.”

The atlas “would not have happened if it wasn’t for him,” said Hornsby, a professor of geography and Canadian Studies at the university.

The 208-page book certainly would not have happened without Hornsby and Judd, who served as co-editors and worked on the book for more than a decade on top of their teaching and writing responsibilities. Hornsby and Judd pulled together the research and writings of more than 30 other people, and professional cartographer Michael Hermann of Pennsylvania was hired to create custom maps that illustrate the state’s story.

“It’s a really important resource, because it’s rare to find something so comprehensive, where you can consult one source that covers such a broad topic,” said Jamie Kingman Rice, director of library services for the Maine Historical Society in Portland. Since the publishing of a state atlas in 1976, “there really hasn’t been an effort to consolidate this kind of information into one publication.”

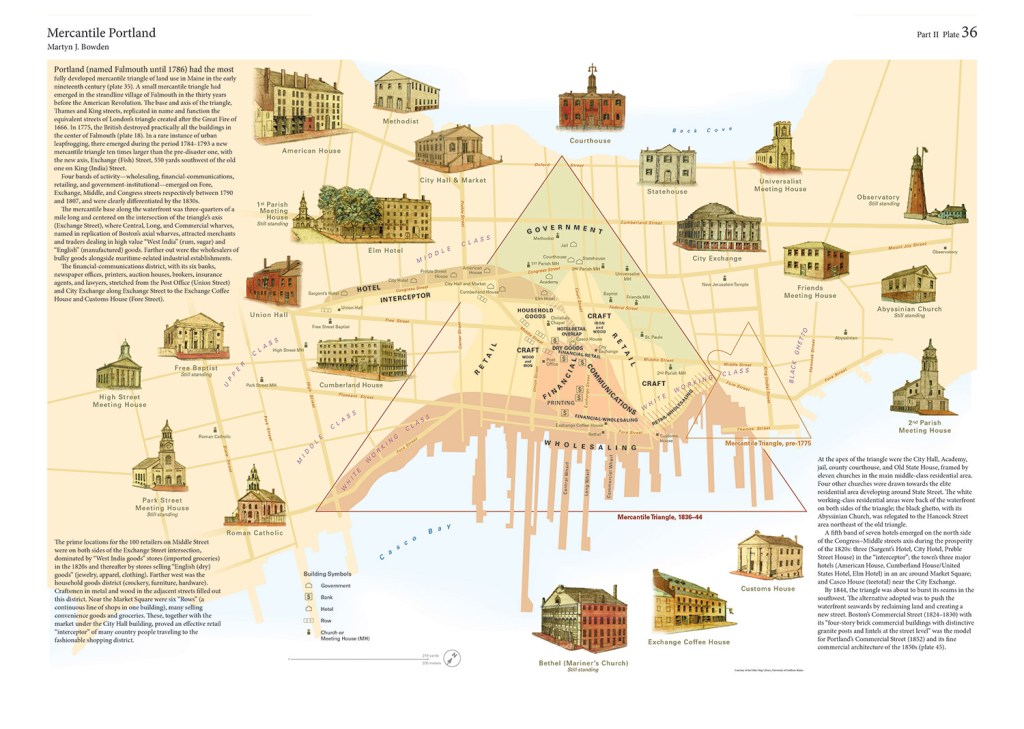

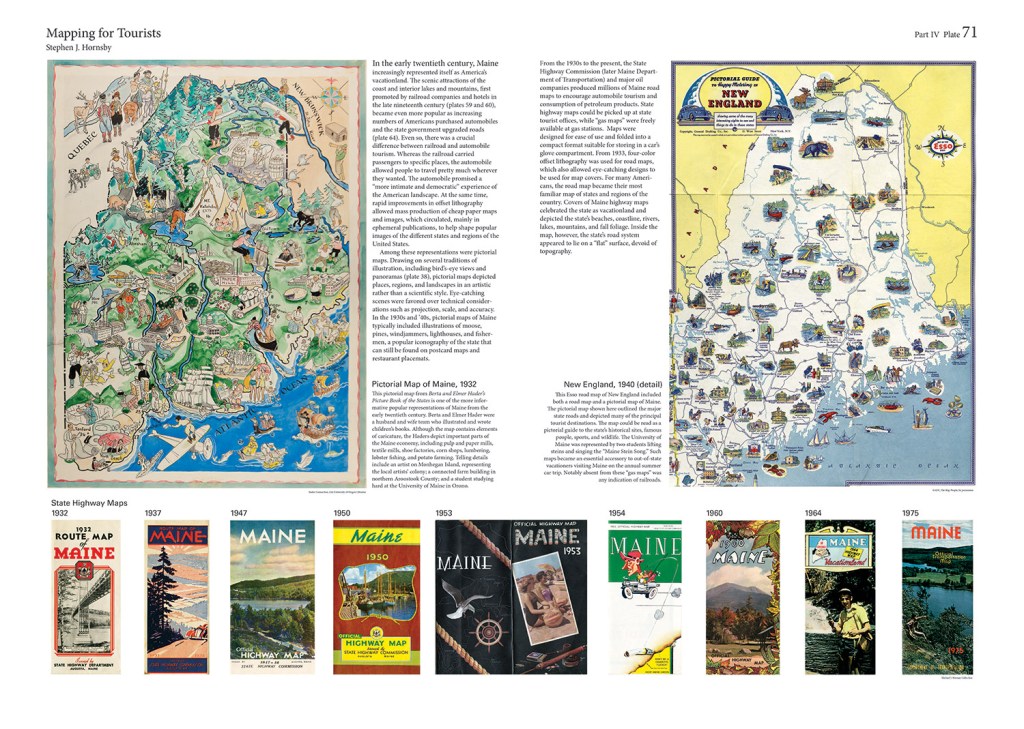

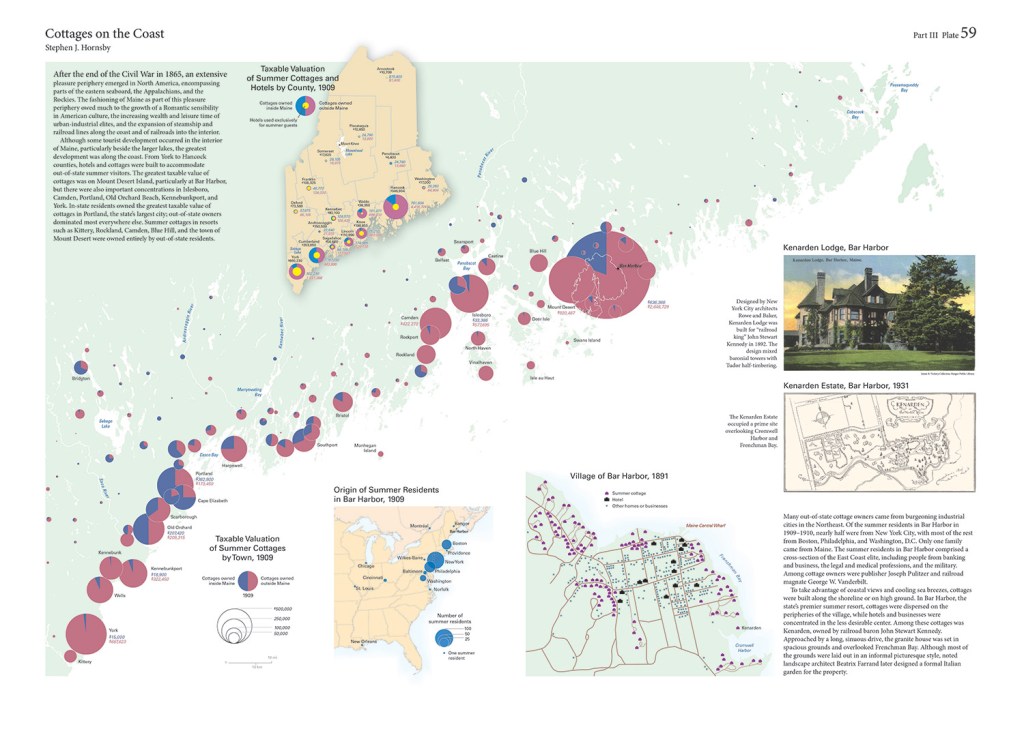

Hornsby said one of the main differences in this atlas, compared with older ones, is the volume of maps and how each has reams of specific information behind it. In past years, an atlas might feature the same basic map on different pages. On each page, something different would be superimposed, highlighting rivers or settlements or something else, Hornsby said.

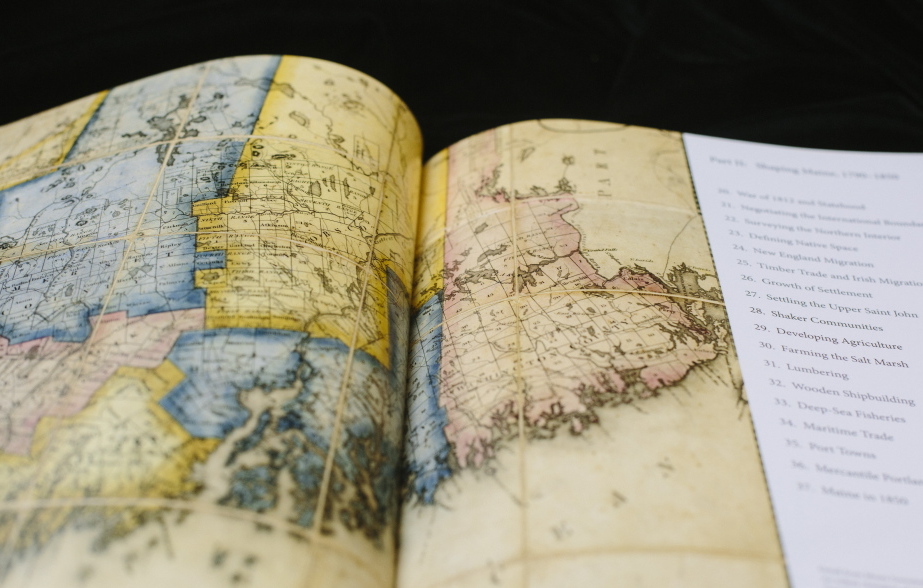

But the maps in “Historical Atlas of Maine,” priced at $65 now and $75 after Jan. 1, are each tailored to serve a different purpose. All are in color and often accompanied by color images of the period illustrated. The book can be ordered online from University of Maine Press or by phone at 207-866-0573.

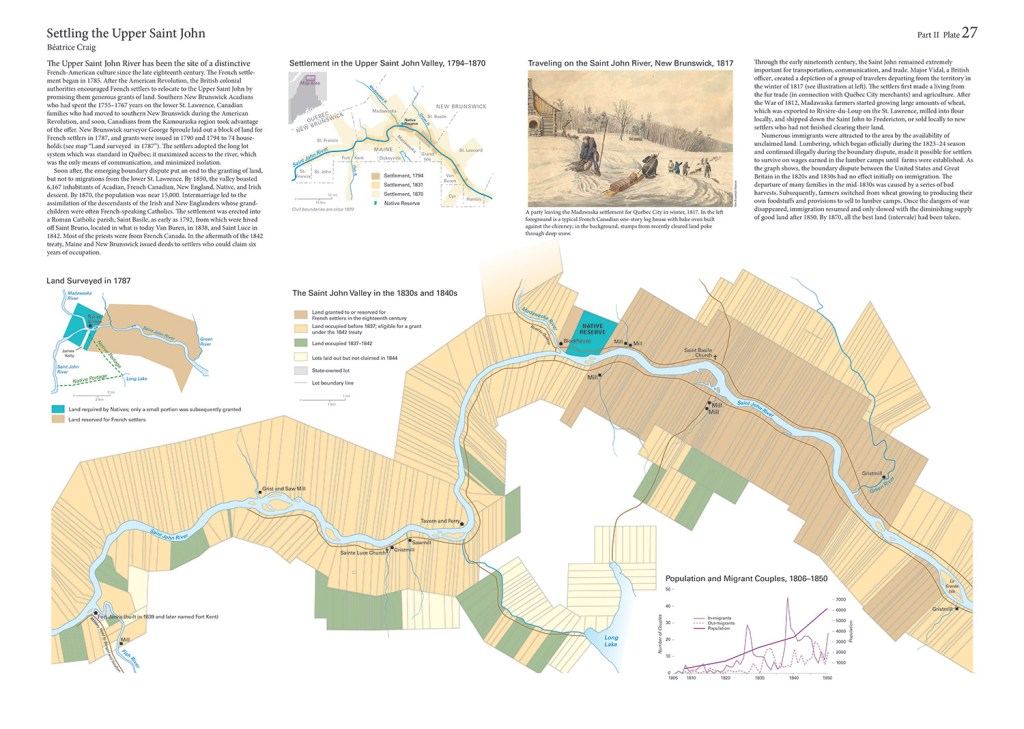

For example, a series of three maps details settlement of the St. John River Valley, on the Canadian border, from the late 1700s to the mid-1800s. The centerpiece of the section is a two-page map, with a 1-inch-to-1-mile scale, showing specific developments along the river from Fort Kent to past Madawaska in the 1830s and ’40s. The map shows grist mills, taverns, ferries, sawmills and churches that existed at the time, plus hundreds of individual plots of land. It labels which were occupied, which were granted to French settlers and which were state-owned.

Above the map is a reproduction of a work of art, in color, showing settlers leaving Madawaska for Quebec City in 1817.

“These are very detailed, lot by lot, based on actual surveys of the time,” Hornsby said. “What we’ve done is arranged the maps to fit the information, which is very different than previous atlases.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.