When U.S. soldiers came ashore in Europe and the Pacific during the Second World War, they carried M1 rifles and M1919 machine guns. Many of them were also packing ASEs – Armed Services Editions. Books might not shoot a shell, but they became vital components of the GI’s mental armor; stories abound of soldiers ditching all their gear except for the paperback stashed in a pocket or in a pack.

The series exposed countless GIs to the classics of world literature and helped forge a generation of readers.

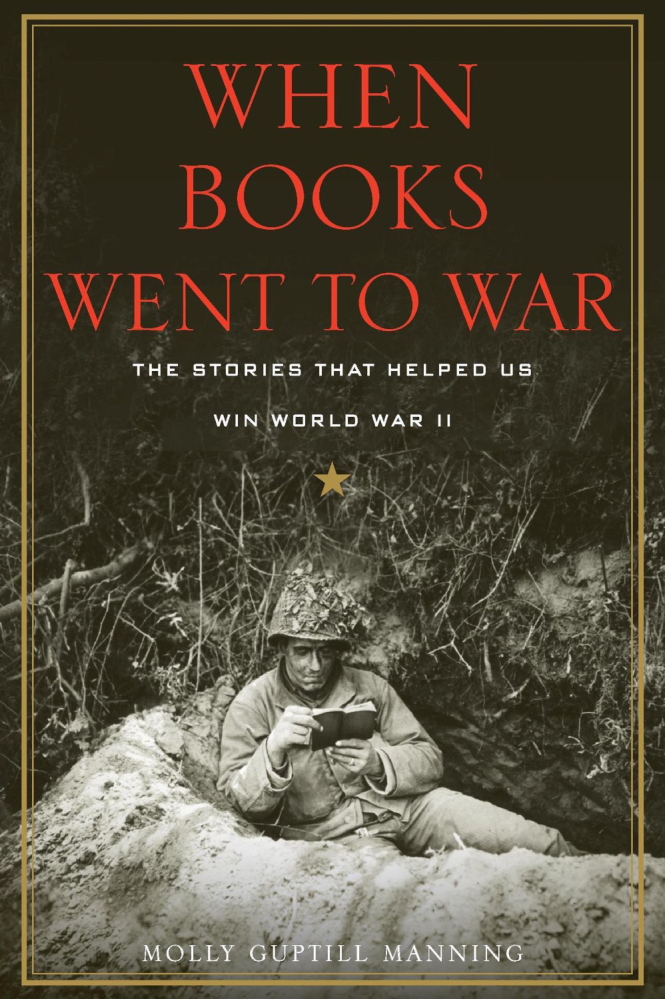

In “When Books Went to War,” author Molly Guptill Manning tells the fascinating story of how the military teamed up with New York publishers to bring books to the troops in the field. From the foxholes of France to the bug-infested jungles of Guadalcanal, ASE books were coveted items, even more than cigarettes.

Armed Services Editions, Guptill writes, “were the most dependable distraction available on all fronts. Whenever a soldier needed an escape, an antidote to anxiety, relief from boredom, a bit of laughter, inspiration, or hope, he cracked open a book and drank in the words that would transport him elsewhere.”

Manning is a terribly earnest stylist, and her fumbled attempts at melodrama don’t come off. Book drives and committees of librarians aren’t exactly scintillating, but her eye for zesty quotes – Manning makes excellent use of soldiers’ letters – is spot on. This material carries the book after a plodding start.

As Manning shows, there was a propagandistic side to the military’s efforts. In contrast to the Nazis, who burned books and banned Hemingway, America would promote freedom of thought and give its soldiers books of all kinds. The state of Army libraries was deplorable, however. The American Library Association swung into action, organizing a Victory Book Campaign, imploring Americans to donate books. The result was a case study in Be Careful What You Wish For – Americans gave away books by the millions, but a lot of them were useless castoffs such as “How to Knit” and “Theology in 1870.” It was time for plan B.

The Army Special Services Division had already mastered the distribution of periodicals, and this model was used to develop books in a smaller format – portability was a key factor. New York publishers, led by Malcolm Johnson of Doubleday, and Pocket Books’ Philip Van Doren Stern, formed the Council on Books in Wartime and fashioned “a new style of book suitable for mass production while operating under wartime restrictions.” (Paper rationing was just one obstacle the team faced.) The results were appealing – a softcover book, printed in double-column format designed to be easy on soldiers’ eyes under stressful conditions.

The first series that rolled off the presses in September 1943 included Graham Greene’s “The Ministry of Fear,” Herman Melville’s “Typee,” and James Thurber’s “My World and Welcome to It.” The series would be remarkably eclectic – high art and history mingled with pulp fiction potboilers and westerns. Katherine Anne Porter’s short stories struck a nerve, and Betty Smith’s “A Tree Grows in Brooklyn” was a favorite.

Soldiers clamored for two racy novels, “Forever Amber” and “Strange Fruit.” One soldier wrote in to tell the Council to pay no attention to scolds – “if the legion of decency approaches you, please leer at them in your most offensive manner and tell them to stuff it.”

Soldiers were an opinionated lot, but their enthusiasm and gratitude shine through these pages. After one Marine stationed in the Pacific, bored out of his mind, picked up “Typee,” he wrote rapturously, “Hot stuff. That guy wrote about three islands I’d been on!”

Still, there were bumps. Republicans tried to police the content of books, fearful certain titles would influence soldiers to vote for Roosevelt, standing for a fourth term.

All told, some 123 million ASEs were printed. Manning rather too neatly wraps things up in a bow. She mentions only in passing F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “The Great Gatsby,” whose canonical status, no sure thing in 1944, was arguably cemented by its inclusion.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.