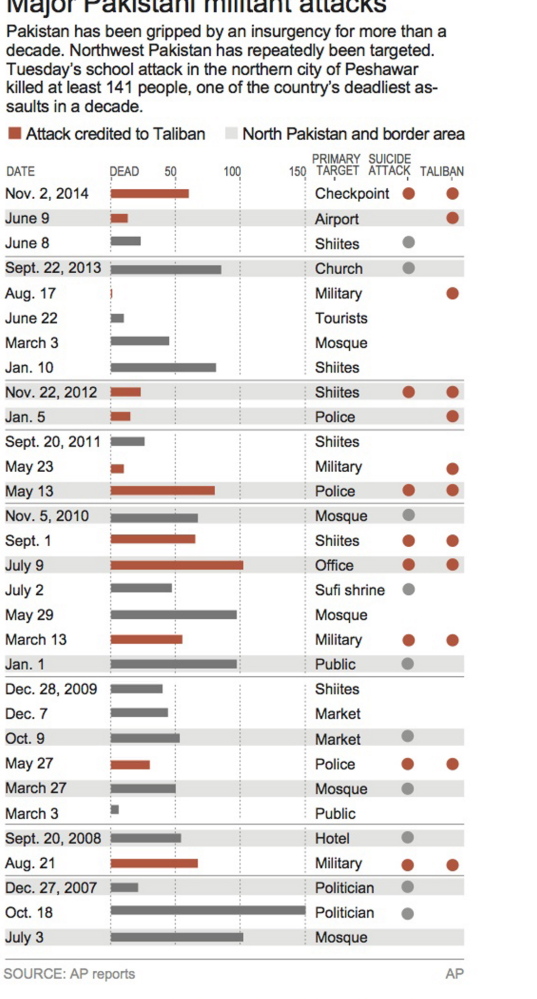

A horrific attack on a military-run high school in Peshawar, Pakistan, has killed at least 141 people, 132 of whom were children and teenagers. The slaughter, carried out by Taliban terrorists, is the single worst terror attack in the country’s history and one of the most brutal assaults on a school anywhere.

The Pakistani Taliban asserted responsibility for the massacre, calling it retaliation for the military’s campaign against the militants’ strongholds in the tribal areas along the border with Afghanistan. For the Pakistani Taliban, schools are vulnerable, “soft targets.” By some accounts, the group has struck at more than 1,000 schools in the country since 2009.

These include many schools for girls. In areas under their watch, the militants seek to discourage female education. The conspicuous defiance of one Pakistani schoolgirl, Nobel laureate Malala Yousafzai, nearly got her killed in 2012, when Taliban militants attempted to gun down the teenager and a few of her friends.

The Pakistani Taliban emerged around 2007 as a loose coalition of militant factions in Pakistan’s restive border areas. It is an indigenous movement that largely targets the machinery of the state and Pakistani citizens, and wants to impose shariah law on the country. Defeating the group, though, has proved bewilderingly difficult.

Here are some reasons why:

• Complex geopolitics: The Pakistani Taliban’s insurgency festers in a complex geopolitical landscape. The group’s top warlords swear fealty to Mohammad Omar, the totemic leader of the Afghan Taliban, an institution that is still linked to elements of the Pakistani military and state and whose leadership still finds sanctuary across the border in Pakistan.

The group draws its support in largely Pashtun areas neglected by both the Pakistani and the Afghan state. Religious seminaries, known as madrassas – many set up with funding from countries such as Saudi Arabia – helped incubate the brand of puritanical fanaticism that defines the Taliban movement.

But since the 2001 U.S.-backed war in Afghanistan, which ousted the Afghan Taliban, the militants have been forced into retreat and guerrilla war. Their designs on taking power look checked, but their insurgency is resilient. Terror attacks, suicide bombings and destabilizing strikes such as this school massacre have become the Taliban’s signature in both countries.

• Political waffling and appeasement: Pakistan’s politicians have in the past been reluctant to fully confront the Taliban menace. After coming to power in the summer of 2013, Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif and other key politicians spent months attempting to hatch a peace process with the Pakistani Taliban. There was even a cessation in U.S. drone strikes against the militants – attacks that had been quietly enabled by the Pakistani military and state, yet denounced by many politicians in public. But the proposed talks fell through, in part because of the continued violence and terror waged by the Pakistani Taliban.

• Conspiracy mongering and denial: It doesn’t help that some within Pakistan’s intelligentsia and elites still try to distract from the root problems and peddle delusional theories about the involvement of foreign actors. Even as the nation reacted in horror to the school massacre, the same conspiracy theories were trotted out. The attack, one Pakistani analyst said, was the product of the collusion of Afghan and Indian intelligence services. There is no evidence that India’s security apparatus has abetted the Pakistani Taliban, an organization that has no love for the Hindu-majority state. But the proliferation of these theories is now commonplace in Pakistan. And it’s a major impediment to confronting a history of tolerating and encouraging regional militancy, for which only the Pakistani state is to blame.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.