Rebecca Goodale was vacationing in western Maine and looking for creative ways to fill her week.

She noticed an ad for a papermaking workshop at a local farm. The tagline got her attention: “Bring a cardboard box.”

Goodale was impressed with the instructor’s ambition. “It was clear we were going to make a lot of stuff,” she said.

The instructor was Richard Lee, one of the most gregarious and energetic contemporary artists in Maine. Goodale came away with much more than a box of paper that day. She left the workshop with enthusiasm for the material and has since become one of Maine’s best-known makers of artist books.

As coordinator of the Kate Cheney Chappell ’83 Center for the Books Arts at the University of Southern Maine, Goodale was instrumental in arranging the latest exhibition in the school’s Glickman Library, “Richard Lee: Paper Trails.” It includes books, collages, travel journals and other items made by Lee, who died at age 75 in 2008.

“Paper Trails” is the first exhaustive look at Lee’s work since his death, his longtime companion Christine Macchi said. Macchi, who directs Maine FiberArts in Topsham, curated the show in coordination with Goodale and another longtime friend of Lee’s, Arlene Morris.

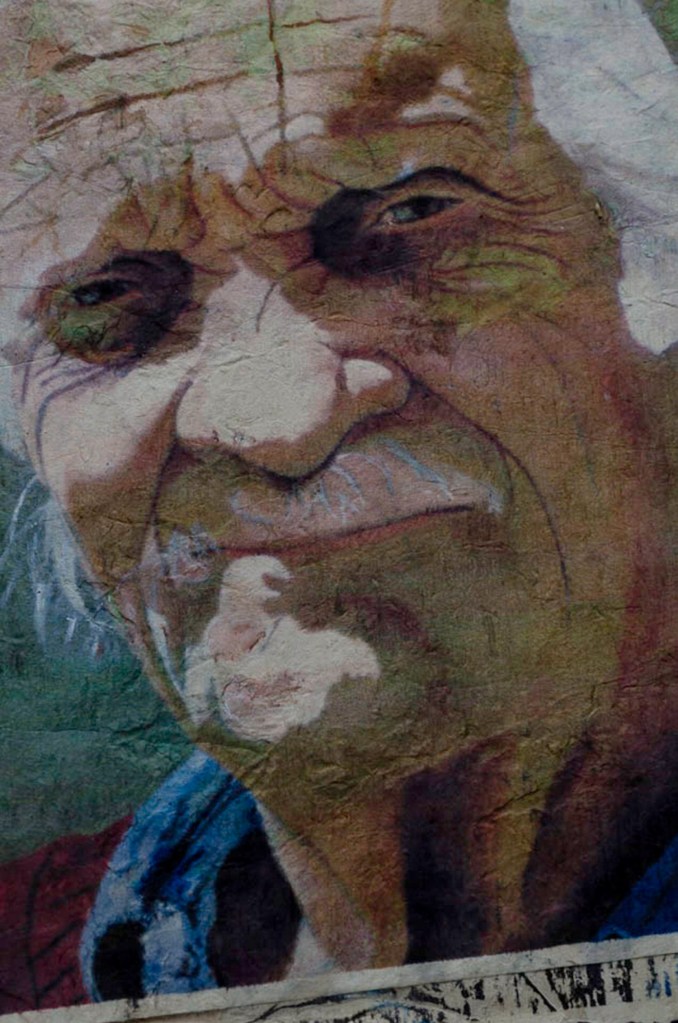

Lee was a tall, robust man with a puff of white hair and an ever-lasting smile. A philosophy major in college, he lived as young man in a New York loft and made his life as a non-representational painter.

He was a lifetime traveler and moved his young family to Greece when he took a teaching job overseas. He visited places like Cuba, Peru and Ecuador. In the final year of his life, he took an extended trip to Istanbul.

But it was Maine that lit his artistic flame. After moving to Maine in the 1980s, Lee became obsessed with paper. Part of his obsession stemmed from Maine’s pulp legacy, Macchi said. “I’m going to learn how to make paper, and then I’ll teach everybody else how to make paper,” she recalled him saying.

He lived up to his word. Over the next two decades, Lee traveled across Maine teaching school kids and adults like Goodale how to make paper. His workshops were known for being loud and fun. School kids loved Lee because he encouraged them to get messy. Adults liked him because they appreciated his raw enthusiasm – and because they came away with tangible results of their effort with sheets of handmade paper.

“Richard was an exceptional teacher,” Goodale said. “He had a big personality, and he was full of energy. He was ambitious and confident, and he had an amazing ability to reach people and inspire them.”

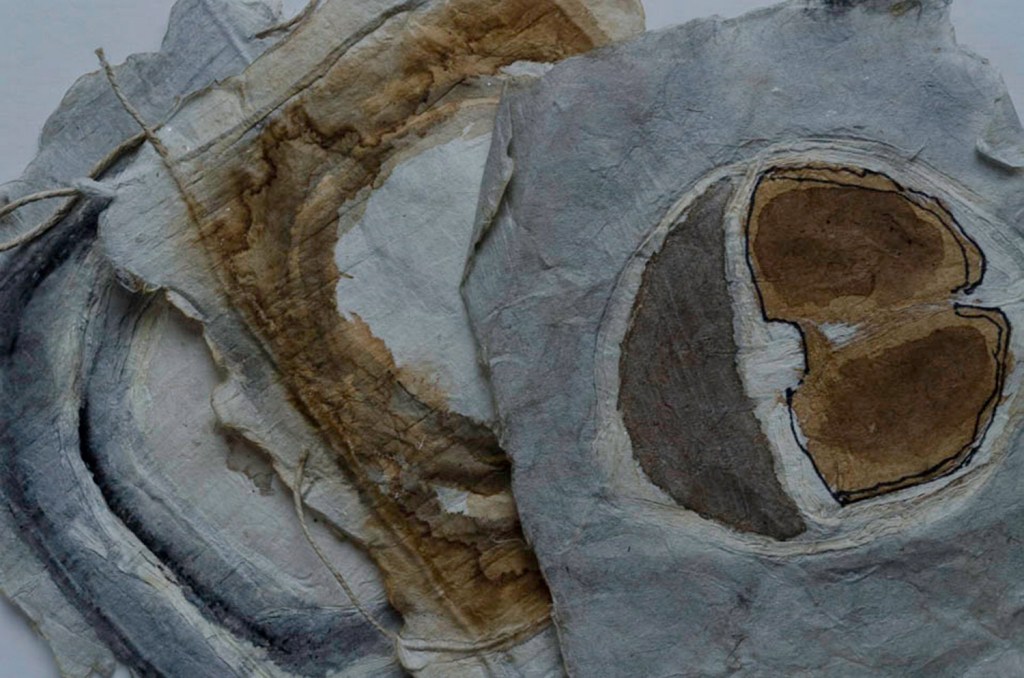

Lee took his first papermaking workshop with his daughter, Cathy, in Chiapas, Mexico. “They were using bark in interesting ways, and Richard wanted to learn the technique,” Macchi said.

Over time, he specialized in Japanese kozo fiber.

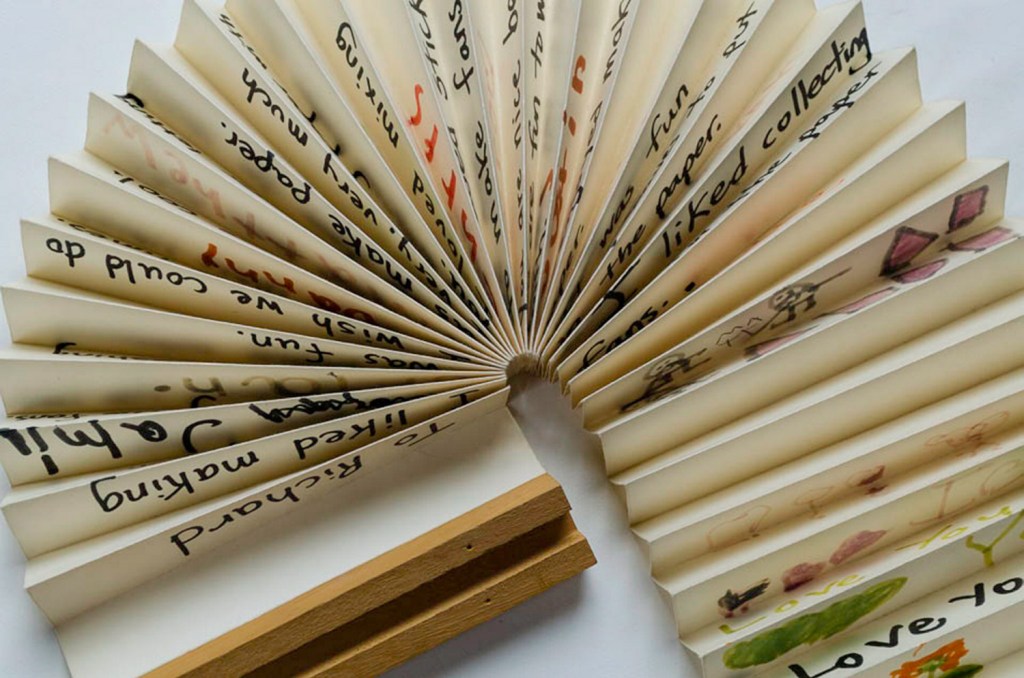

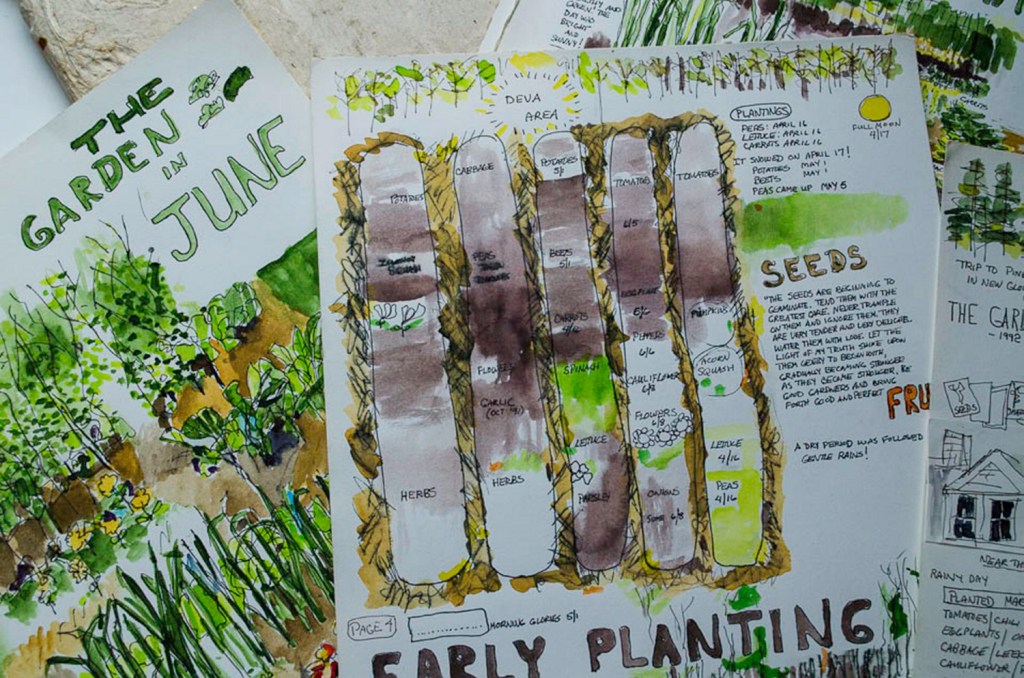

Because of the nature of the Glickman space, most of the work on view in “Paper Trails” is small and under glass. It includes journals of Lee’s travels, with his hand-written travelogues scratched on pages bound by string. His journals include watercolor paintings, drawings and embedded things he collected along the way, including mica, an old shirt pocket, scraps of newspaper, Mexican stucco, Grecian marble and a piece of toast from a bed and breakfast.

Goodale is certain the under-glass aspect of the show would distress Lee, who was a hands-on kind of guy. “He wanted people to hold everything and to touch the books,” Goodale said. “But we can’t do that with this unsupervised space.”

When Macchi gives a talk about Lee and his work on April 22, she will bring examples to pass around. She wants people to understand the tactile, functional nature of handmade paper, which was important to Lee.

“He always wanted people to handle the work. He would say, ‘Nothing is too precious. … Nothing is forever.’ ”

Lee expressed his life of adventure in his art. His journals recount his travels. His collages, which sometimes include stones, reflected his environment. Lee was curious about man’s relationship to the earth, Macchi said, and he explored his questions and observations in his work.

His art responded to his place – not what it looked like, but what it felt like to him, she said.

One of his former students, who became a friend and shared studio space with Lee in Richmond, said Lee related his paper to the inner skin of a tree. He viewed his work as an extension of nature, Diane Green Hebert said. He saw his art as a way of giving trees new life, she said.

Hebert, who lives in Rockland, met Lee in a papermaking class at his Richmond studio. He taught her to use paper in sculptural form. She became a mask maker because of Lee’s lessons, she said.

Her favorite memories of Lee are of sitting in the studio together. Each would be working on a project, and the conversation would drift from topic to topic. “He just gave you space and carried on doing his own work. He talked about how he was doing his work and talked about the experience of his work,” Hebert said. “He could be a bit of curmudgeon, too. He could moan and groan. But he was an exceptional human being.”

Goodale always appreciated Lee’s honest approach to his material. “He had a special relationship with the pulp,” Goodale said. “He didn’t ask his material to be something it wasn’t. He wasn’t the boss. He was the conduit.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.