Mark Berry grew up in Scarborough playing in the woods near his home. But as a kid who had the chance to summer at his grandparents’ house in Washington County, he felt the pull to Maine’s wild lands early in life.

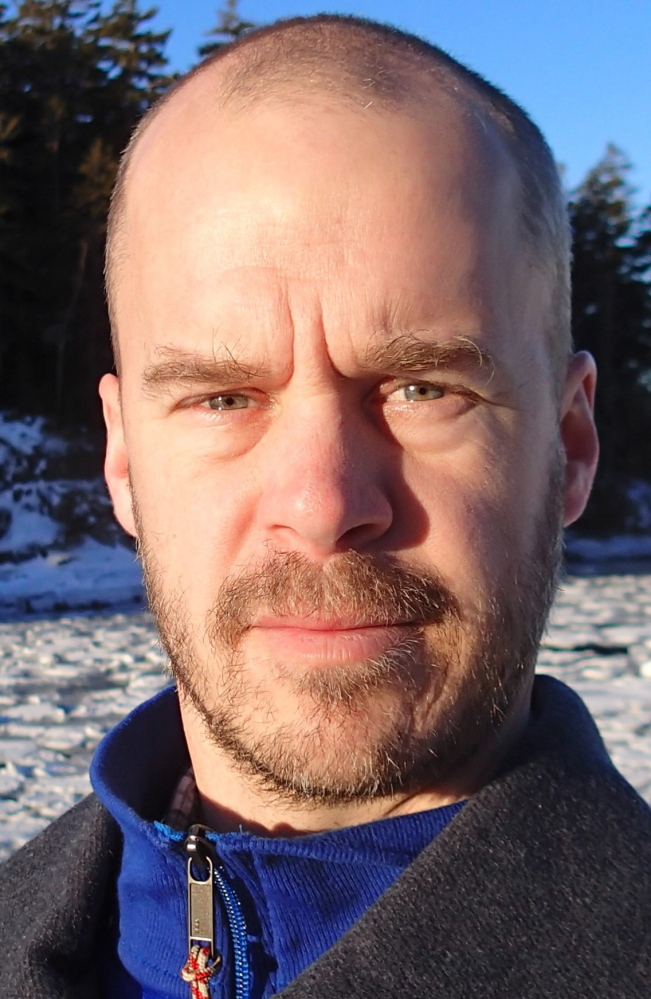

Now 42, Berry is the president and CEO of the Schoodic Institute, a nonprofit organization that works with rangers at Acadia National Park to inspire people to explore outside.

The Schoodic Institute, founded in 2003, has undergone a transformation in the past year – and Berry has had a hand in directing it on a new path.

For a guy who grew up in Maine before leaving to study and work in conservation elsewhere, having the chance to grow an outdoor organization here has meant more than the chance to come home. It’s been a dream job.

Lots of people know the Schoodic Peninsula, but what is the Schoodic Institute?

It was founded in partnership with Acadia National Park when the Navy left their base at Schoodic Point in 2003, and the idea was to create a research and learning center in partnership with the national park. It’s a new concept for the park service, but it’s starting to happen at other sites around the country. The infrastructure from the Navy base created an opportunity, but also significant challenges. The campus required substantial renovation. And they realized they needed to develop partnership and programs; those were not just going to happen. The work to renovate the campus got a big boost from some federal stimulus funding. Now we have a really attractive campus that in many ways is what you’d find at a small college.

So what does the institute’s evolution mean for Maine?

I think it means something for all Maine people, maybe mostly for those who might not identify themselves as outdoor people because we are working to help connect people to the natural world. Our tools for that are science, research and education, and also art. A focus for us is the citizen-science approach, to give opportunities for people to participate in science not only as a way to appreciate that science, but also to advance an understanding of outdoor issues.

What are some examples of what you’re talking about?

Examples are people having the opportunity to participate in projects like the hawk watch, observing the migration of raptors in the fall, which they do from the top of Cadillac Mountain, or the sea watch, observing the migrating seabirds from the tip of Schoodic Point. There are lots of opportunities to participate in projects that are educational opportunities and real research.

Is there a demographic you’re trying to reach?

We are very interested in life-long learning. We have some partnerships with the park that focus on Maine school children. Every fall we have up to 600 elementary and middle school kids come through programs. It draws largely from the local area, but also Aroostook County and western Maine. Some schools are traveling hours. Every year there are kids who have never seen the ocean. Even at that basic level, they get an exposure to natural resources they otherwise might not get.

What’s the institute’s future?

I am confident that you are going to see a lot of programs and new partnerships that will help us reach beyond the local area and have a leadership role in building the field of citizen science. The Citizen Science Association has its first conference in San Jose this month. We are helping to launch that organization. Our first priority is in building partnerships and supporting Acadia National Park. The park is a great place to try things that, because of the national park service, have a chance to explode and go quickly to the national level.

What’s an example of that?

We have a partnership with the University of Maine that developed through a program called Acadia Learning, where students collect dragonflies from watersheds because dragonflies accumulate toxins. They are a good way to measure mercury in water. Kids gather dragonflies by mucking around in ponds, and scientists at UMaine can use them to get the level of mercury. By doing this, students help produce a picture of the mercury contamination in the environment. The National Park Service picked it up and it’s now at 50 parks across the country.

You grew up in Maine, so how does it feel to help Maine outdoor organizations?

I grew up in Scarborough but also (visited) my dad’s parents in Washington County. I probably had a deeper connection to nature coming to the Downeast region. I left Maine after high school but always had an idea I would like to live and work in Maine. I got that chance with the Downeast Lakes Land Trust, which brought me back to Maine from Oregon. The move to the institute (last June) looked like an amazing opportunity. I think the two areas that seem the most important to me are in conservation and in connecting people to the natural world. The Schoodic Institute has an opportunity to contribute to both. And it is in one of the most spectacular places in Maine.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.