KANSAS CITY, Mo. — The woman’s voice on the intercom was anguished.

“There’s a shooter in the building. Lockdown! Lockdown!”

Inside the library at Independence’s Pioneer Ridge Middle School, about 65 teachers and staff members – who knew this was all pretend but were warned it may be unnerving – assumed their positions under desks and crouched between rows of children’s books.

Someone switched off the lights as instructed. Maybe the gunman won’t see them hiding. The rest of the school stood empty.

It was part of training increasingly occurring in the nation’s schools, hospitals and other workplaces to drive home lessons on how not to become an armed intruder’s sitting duck.

“Lockdown! Lockdown! He’s getting close to the library.”

Independence Police Sgt. Chris Summers entered with a steely expression and brisk gait. He carried an Airsoft pistol filled with plastic pellets. The lights came on and he weaved around the shelves, firing.

An officer following him sounded an air horn representing each shot.

“You’re shot,” Summers said, tapping the gun barrel against the thighs of three teachers huddled behind a table. No point pulling the trigger on them, close as they were.

Eliminating that huddle took three seconds.

The killer played by Summers had dozens of others to finish off, quickly as he could, to show the teachers what’s likely if they do nothing but try to hide.

Not all “active-shooter” drills simulate someone firing and people supposedly dying. But lessons are more apt to stick, police and security consultants say, when the real thing can be replicated without anyone getting hurt.

The ultimate point is to present human targets with options beyond the traditional response of locking doors, switching off lights and hoping the gunman doesn’t spot them.

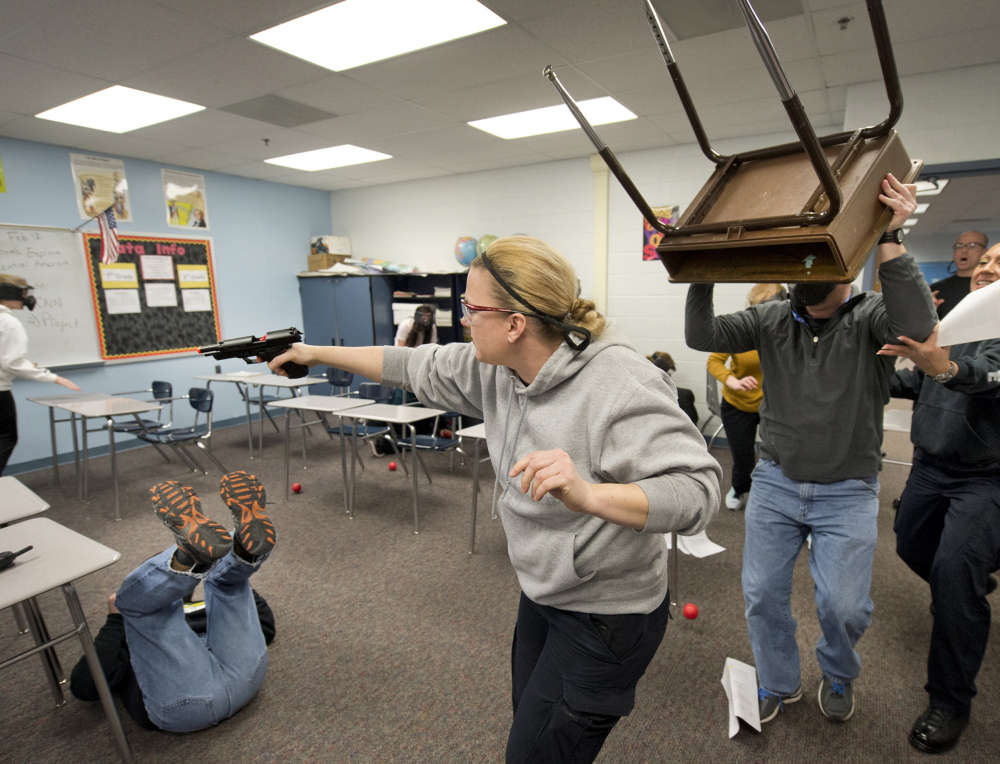

How about dashing to exits, tossing objects, even overcoming the gunman?

“Things are moving in that direction,” said Paul Fennewald, director of the Center for Education Safety, a partnership of law enforcement agencies and the Missouri School Boards Association.

‘YOU NEED OPTIONS’

The thought of encountering an armed intruder and, as a last resort, fighting back “isn’t in the mindset of the education culture,” Fennewald said.

“But you look at where we are as a society now, you’ve got to get your mind around it. … You need options. You can’t just lay down in a fetal position and die.”

Some critics shudder at the basic tenets behind a fast-growing protocol called Run, Hide, Fight, especially as it applies to schools.

They contend that in some situations the lessons could result in more deaths than might occur in a basic lockdown.

That criticism is apart from the questions surrounding how some workplaces get the lessons across to their employees. In other areas of the country that have initiated high-tension drills, injuries have resulted and employees have complained that the role-playing is too much.

The Independence drill employed the principles of one of the more common training programs, known as ALICE.

Summers shot 90 percent of those library occupants. All fake deaths and injuries happened in less time than the five to six minutes it would take for police to arrive in a real emergency.

After the demonstration, the teachers and office workers rose amid nervous laughter, though some soon were dabbing at tears with tissue. That was while they listened to a 911 call from a terrified Columbine High School librarian during the 1999 assault that left more than a dozen dead.

In the next exercise, Pioneer Ridge educators learned to run down empty hallways to nearby exits.

Next, they used desks and chairs to barricade their classrooms. They were told that in a real-life event it’s OK to crawl out windows.

Next, they threw plastic balls and learned to physically swarm a gunman, separating gun from intruder and pinning that person to the floor. Nobody should be holding the gun when police arrive, they were told, because officers will be targeting the gunman.

The group applauded at the end of two hours of instruction and exercises. One employee shouted, “Empowered!”

Eventually, such lessons will be made age-appropriate and passed on to pupils, school officials said.

Here and across the nation, the strategies for survival are pitched under different names: Escape, evade, engage. Get out, hide out, take out. Flee, fade, fight.

But the idea is the same: Provide options, and the safest one may not be crouching in the dark.

‘UNCHARTED TERRITORY’

In December, a national report on drills simulating school shootings called the rising practice “uncharted territory” and urged districts to proceed cautiously, especially when youngsters are involved.

“We really don’t know the effect of these drills. We need to know that,” said Stephen Brock, president of the National Association of School Psychologists, which co-sponsored the report with the National Association of School Resource Officers.

Brock cited the rarity of kids being killed by gunmen at schools – “the odds are similar to being struck by lightning three times” – and said some districts may be reacting to intense media attention to the threat.

So far, though, official grievances have been few:

In Colorado, a nursing home worker filed suit after she stepped unaware into an active-gunman drill. Police conducting it allegedly ordered her into an empty room as a “hostage.” Realizing the worker was startled, an officer tried to explain that it was just a drill.

In Farmington, Mo., four teachers complained to the county prosecutor that the drills made them uncomfortable. No legal action was taken and the teachers reportedly resolved their issues with the district.

In Iowa, more than 25 school workers filed for workers’ compensation for injuries that they claim occurred in drills that taught how to wrestle down gunmen as a last resort, said Jerry Loghry of EMC Insurance Companies in Des Moines.

“We have injuries related to running, to tackling, being tackled, running into door jambs, jumping off furniture,” said Loghry, whose company insures most Iowa schools and 1,500 districts nationwide.

ALICE stands for Alert, Lockdown, Inform, Counter or Evacuate. The program is based on concepts developed by police in Houston, Texas, after the Columbine killings. It’s now administered by a private company, the Ohio-based ALICE Training Institute.

“The last count I got, there are 1,700 police departments and 1,600 school districts on board,” said the institute’s founder, Greg Crane, a former Texas police officer.

ALICE instructors travel the country to host two-day seminars that train school officials, law enforcement, security consultants and private companies. The trainees become ALICE-certified and relay what they’ve learned to the places they work.

The C in ALICE – counter – raises concerns among some security experts: Should civilians be taking on a crazed intruder with a weapon? Without knowing an armed person’s intentions, should he be swarmed and tackled, risking lives?

TRAINING TAKES TIME

“Trying to teach all that in a two-hour, four-hour or even 16-hour program doesn’t do it,” said Michael Dorn, a former police officer who now directs Safe Havens International, a school safety organization.

Dorn said he received 80 hours of close-quarters combat training to join a police tactical squad, adding: “I found 80 hours to be inadequate to learn the skills needed when applied under stress.”

But it doesn’t take training to know how to throw a backpack, book or laptop at someone bent on murder, ALICE advocates say.

Heaving papers. Running in zigzags. Anything but freezing in fear might throw a gunman off script, said Alisa Pacer, emergency preparedness manager at Johnson County Community College, where ALICE training has been mandatory for all workers since 2012.

Instead of locking down all classrooms when an armed intruder comes on campus, JCCC’s protocol is to track the whereabouts of the intruder, through video cameras and text alerts, and keep classroom instructors updated. They’ll do what they deem necessary.

Barricade the door. Direct students to a safe exit. Swarm the killer if death is the only other possible outcome.

“I believe it’s all about options,” Pacer said. “Doing nothing gets people killed.”

That was the takeaway for Pioneer Ridge staffers who drilled in Independence.

Courtney Wall, a health care worker at the school, said the most disturbing exercise was the first one, when Summers showed how quickly a gunman could attack a library full of people trying to hide.

“The hardest part,” she said, “was being a sitting duck.”

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.