One hundred and fifty years ago, the Civil War ended, at least on the battlefield. But the end of combat in 1865 brought the beginning of the struggle to translate the Union victory into real freedom for the former slaves.

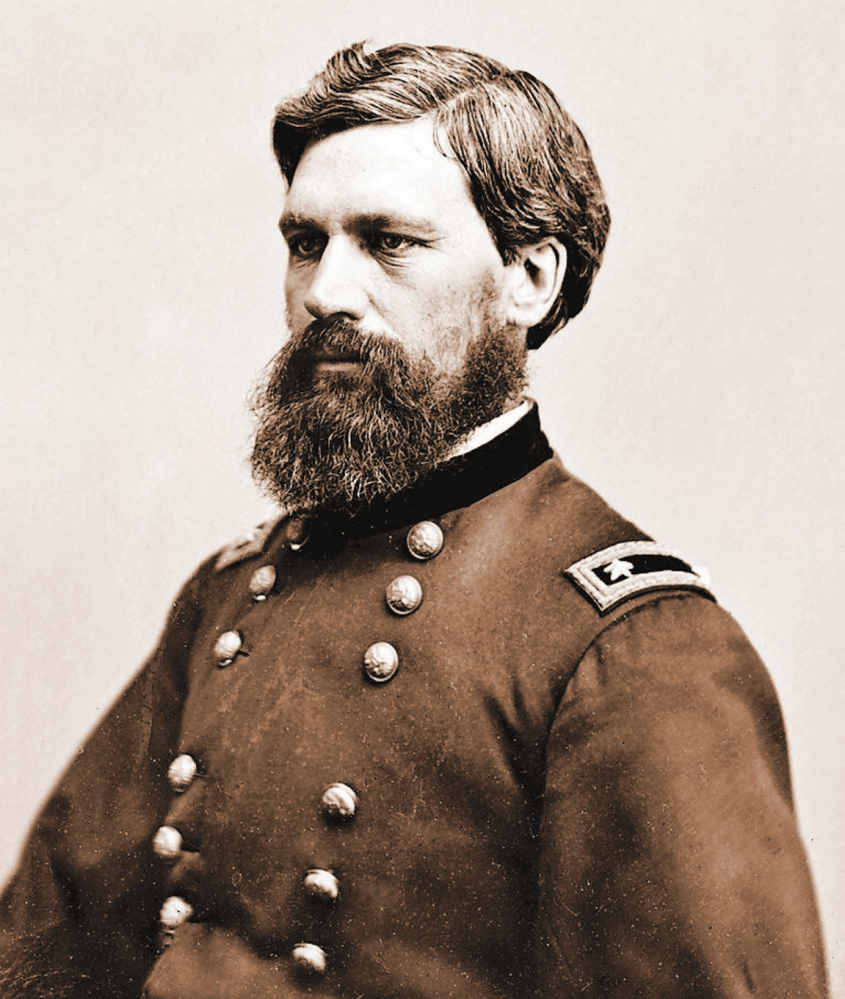

Just before his assassination, President Abraham Lincoln selected Oliver Otis Howard, a native of Leeds, Maine, and a graduate of Bowdoin College, to lead that effort.

Howard, a regular Army general who had graduated from West Point after his Bowdoin years, was named to head the War Department’s Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands, known as the Freedmen’s Bureau.

The Maine man was uniquely qualified for the responsibility. After an unfortunate start on the battlefield, Howard matured as a field commander. He became one of the top deputies of Gen. W.T. Sherman, the leader of the Union armies in the West. Though of vastly different temperaments, the two men grew close.

Early in the war, Howard lost his right arm in battle. Eligible to retire, Howard was offered the Republican nomination as candidate for governor of Maine. Though there was little doubt he would be elected, he chose instead to return to the battlefield.

The only military decoration at the time was the Medal of Honor, given to Howard and more than 1,500 others. But Howard also received a vote of thanks from the Congress, accorded to less than two dozen in the Army, for his action is selecting the advantageous ground for the Union forces on the Gettysburg battlefield.

In the great two-day victory parade in Washington, D.C., at war’s end, Sherman insisted that Howard ride beside him at the head of the Western forces. Holding the reins of his horse, Howard would be unable to salute the president as he passed.

What recommended Howard most for leadership of the Freedmen’s Bureau was not only his battlefield actions, but his reputation as the “Christian general.” Having undergone conversion early in his military career and after brief consideration of becoming a minister, Howard demonstrated unselfish compassion for others.

His view toward the freedmen, a group including women and children despite its name, was not merely that they should be emancipated from slavery, but that they should enjoy full equality with other Americans. They should gain access to education, be able to vote and become full participants in the political process.

At the time he took office in May 1865, Howard enjoyed the strong support of Secretary of War Edwin Stanton and of the Republican majority in Congress. The 1864 elections had brought to office Republican congressional majorities embracing policies aimed at punishing the South and elevating African Americans.

The “abandoned lands” were plantations from which southerners had been driven in the war. Though they were insufficient to provide every former slave family with the “40 acres and a mule” that some had thought was promised, Howard planned to help some former slaves get a start in farming.

If this was an optimistic view, Howard was even hopeful that the vanquished South would learn a lesson from the war and adopt a more favorable attitude toward the freedmen. People formerly forced to labor against their will and without compensation could become paid employees, free to leave the plantations if they chose.

With Lincoln’s death, Andrew Johnson, the Tennessee Democrat who had been his bipartisan running mate, became president. While he had opposed secession by his home state, because of his strong belief in the Union, he was a former slaveholder who sought no basic change in the social structure of the South.

Johnson remained loyal to the traditional Democratic policy. In his view, the South should not be punished and should be free within the Union to shape its own relationship with the freedmen.

Johnson’s views set him on a collision course with the so-called Radical Republicans who dominated Congress. Howard was caught in the middle, trying to do the job set for him by Congress but at odds with the president. As a military officer, he had no choice but to follow the increasingly restrictive policy of the commander in chief.

The president quickly moved to nullify Howard’s efforts to distribute abandoned lands, and allowed them to be returned to their southern owners. But when he vetoed legislation to expand funding for the Freedmen’s Bureau, Congress openly challenged the president by overriding his veto.

As Howard struggled to find ways to aid the freedmen, the battles between Johnson and the Radical Republicans escalated. Johnson wanted to get rid of Secretary Stanton, who was closely aligned with the Republicans. But Congress passed a law over Johnson’s veto intended to prevent him from removing cabinet members without the Senate’s consent.

Claiming the law was unconstitutional, Johnson removed Stanton. This action led to his impeachment by the House of Representatives. But, by a single vote, the Senate refused to remove him from the presidency. One of the courageous Republican votes for Johnson was cast by Maine Sen. William Pitt Fessenden, who believed that the president had acted within his authority.

As this conflict wore on, Howard increasingly had to give way to Johnson’s policies, despite the support of Fessenden and other Radicals. He saw funding for his Bureau gradually cut.

His experience had made Howard more of a realist. While he understood the South would not be punished and the new amendments were not likely to be enforced, he focused on education as his highest priority. If African Americans gained more education and had more trained leaders, they might fight effectively for their own rights.

The elementary school system in the South was weak, and, after Reconstruction, the states could close schools to African Americans. But institutions of higher education were privately financed, mainly by religious organizations, and could survive as the South returned to its old ways. Howard directed millions of dollars in bureau funds to them as well.

These institutes and universities grew across the South. The summit of the system was to be a new university in Washington, which would teach liberal arts, law, medicine and the full range of advanced studies. This university would be open to men and women of all races.

The university was chartered by Congress, and the new governing board decided that it should be named Howard University. So it happened that what was meant to be the leading academic institution for blacks in the United States was named for a white man from Maine.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.