“A Gateless Garden: Quotes by Maine Women Writers,” now on view at the University of New England’s Portland Art Gallery, is a strong and thoughtful exhibition.

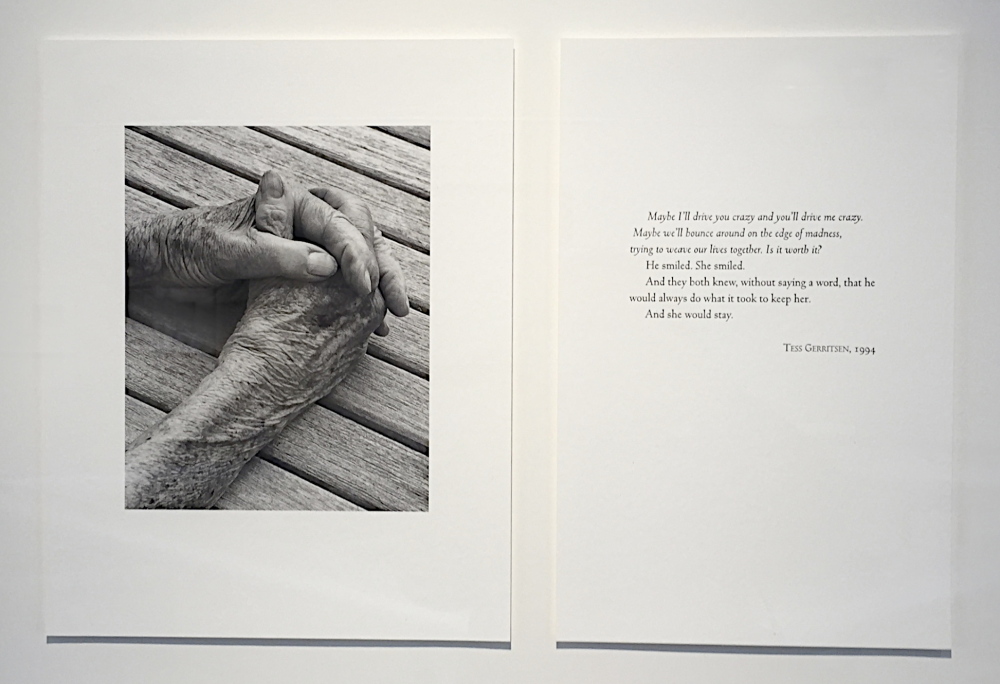

The show features 53 or 106 works – depending on how you choose to divide up the bifurcated objects. Floating in each frame is a photograph by Kerry Michaels and then a quotation by a Maine woman writer printed by letterpress on German etching paper.

I had my doubts when I heard about the show in advance. It sounded like someone was confusing the idea of creating a catalog with curating an exhibition. To a certain extent, that concern was reinforced when I got the gorgeous catalog featuring 100 paired photos and quotes. (About half of which were selected for the show.) It is beautifully printed in black and white with the photos to the left of the margins and the quotes in the featured spot on the right.

The photos are geared toward the local landscape: woods, flowers, coastal scenes, wizened barns and so on. Many include images of people, but they too are depicted as though captured by spontaneously observed snapshots rather than in posed portraits.

The accompanying quotes are succinct and interesting, never lingering longer than a paragraph. They range from sharp-edged pithy bits to quoted passages from ongoing observational third-person narratives.

The catalog was so enjoyable that I set out immediately for the exhibition. And I was well-rewarded.

UNE’s Art Gallery is an excellent venue, but I have never seen it look so good. From the first glance into the space to the closest examination of the framed works, “Gateless Garden” holds up to the closest scrutiny.

The black-framed black and white image of ferns on the forest floor greets and comfortably orients the viewer. It is a much larger image, and it is the only picture that is not paired up with a printed quote inside the frame.

The other objects are all so exquisitely presented that the presentation craft becomes a significant component of the show. This is particularly successful because it allows the letterpress quotes (masterfully printed by Scott Vile) to be seen as prints and not merely handsome blocks of text. The effect of this is subtle but powerful. The unexpectedly rich presence of the framed objects (it’s rare to toast the framer, but major kudos to Kevin Callahan) combines a here-and-now picture presence with a pulsing rhythmic sense of time provided by the literary quotes. Together, these create an almost musically eloquent dialogue between presence and thing – a sort of poetry of place.

One particularly strong pair features Michaels’ photo of a ramshackle shack with its stringy remnants of wizened cedar shingles. The shack’s rectangular shape echoes a dark square opening at its base (barely revealing an old tool-like sculptural form within). The geometrical plight of the scene is amplified by the triangle-topped old barn looming up behind the shack. Beside the photo is a 1923 quote from Kate Douglas Wiggin: “It is not always in gold days, but in gray ones, that the soul grows and the purpose of life unfolds.”

It’s a thoughtful image and we are led to bask in the idea that with its decrepitude, the barn became more photogenic – and more interesting.

Other pieces are friskier. Next to Maine’s version of Paris’ Pont-des-Arts, at which lovers place a lock on a fence and toss the key into the water (rather than the dreamy Seine and its bateaux-mouches, behind a chain link barrier we see lobster boats and a working waterfront), we read Cynthia Voigt’s caustically comic quip, “For a woman, marriage is a natural step after love, so she quite wisely hesitates at love.”

What bubbles up as a question is the stance of “Gateless Garden” toward men. After UNE’s substantial series of exhibitions geared toward women artists of Maine, it’s fair to challenge the drum-beaten theme of shows with “Maine Women” in the title. But whereas the Maine women artists exhibitions purveyed the first-person agency of women as creators, the literary stance of “Gateless Garden” combines with an almost journalistically external photographic perspective to place men in the “Other” space – the once-assumed perspective on women as depicted in Western culture.

One of the pieces that troubled me at first includes a photograph of a man sitting in a boat tied up at a dock on a summer lake. He’s a typical retired guy in Maine: sixty-something, futzing with a fishing rod and clad in a windbreaker, baseball cap and a plaid flannel shirt. We are invited to survey him with the idea – assured by a blurred pine bough repoussoir in the lower right – that he is not aware of our presence. Louise Dickinson Rich’s accompanying 1942 text is assertively workaday, presumably fostered by a practical wartime ethic: “The men weren’t romantic, or daring, or glamorous. But they were something much better. They were good neighbors.”

But what is a good neighbor? Is our fishing friend useful? Competent? Quiet? Considerate?

To a certain extent, the specifics hardly matter. Rich’s text is a shifter – what constitutes a “good neighbor” is left up to you in your own perspective.

“Gateless Garden” is ultimately about perspective both broadly in the sense of content and narrowly in the act of fitting photographs together with text. It may be a precarious balance, but it works.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.