AUGUSTA — The long-running battle over alewives in the St. Croix River will return to Augusta this month, two years after the fish gained access to the river’s upper watershed for the first time in decades.

And judging by the initial political maneuvering, the tension and skepticism over the homely alewife’s presence in the St. Croix have not abated.

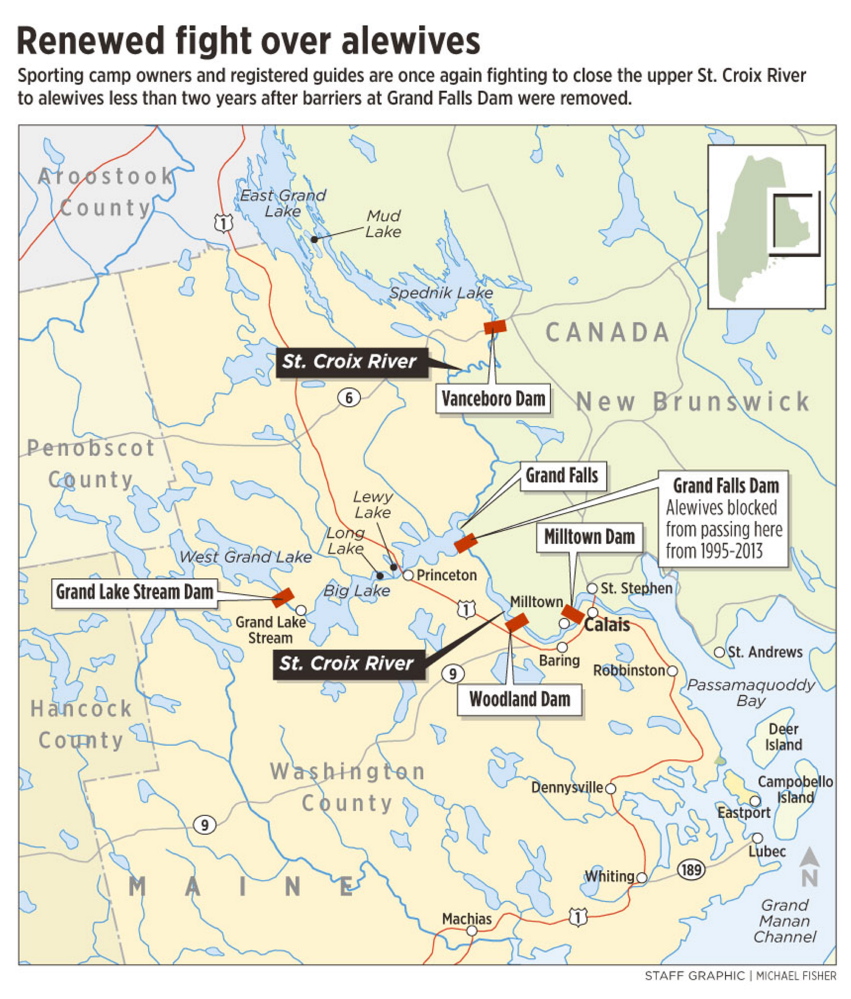

Fishing guides, sporting camp owners and some local officials in the Grand Lake Stream area of Washington County are once again backing legislation that would require the state to prevent alewives, which migrate up Maine rivers to spawn in large schools, from passing above Grand Falls Dam near Princeton. The bill, L.D. 800, will revive an issue that was fiercely debated for more than a decade before federal regulators, and eventually Maine lawmakers, ordered the removal of physical barriers blocking alewives’ upstream passage at Grand Falls in 2013.

For the bill’s backers, the prospect of massive schools of alewives and their offspring infiltrating the St. Croix watershed is a direct threat to the smallmouth bass fishing industry that supports a large portion of the region’s economy.

“We have built our lives around these bass,” said Louis Cataldo, a registered guide and Grand Lake Stream’s first selectman. “Regardless of whether they are native or not, they are a big part of the ecosystem up here in these lakes … and all of these sporting camps, all of these guides are surviving because of smallmouth bass. And not just the sporting camps but the stores and restaurants, too.”

CONTENTION AND MISTRUST

Opponents, meanwhile, are frustrated at the prospect of having to defend a recent hard-fought victory.

“We thought we had taken care of this,” said Paul Bisulca, a former chairman of the Maine Indian Tribal-State Commission who has worked with Maine’s two Passamaquoddy reservations, as well as with Passamaquoddies in neighboring New Brunswick on the alewife issue. “The science is still the same. The science is still compelling. Nothing has changed.”

Passamaquoddy tradition includes fishing for alewives in the St. Croix watershed.

This issue is so contentious – and the distrust so strong – that lawmakers couldn’t even agree on what to do with the bill.

For nearly a month, the Senate and House were stalemated over whether the Legislature’s Marine Resources Committee or the Inland Fisheries and Wildlife Committee – or both – should review the legislation. Supporters wanted to send the bill to the Inland Fisheries and Wildlife Committee, which is often viewed as friendlier to sportsmen. But because alewives are sea-run fish, the Marine Resources Committee has heard the issue in the past.

The Senate finally agreed this week to send the legislation to Marine Resources. The hearing is expected to be held this month; however, the committee has yet to settle on a date for a bill that is expected to draw a large crowd.

Sometimes referred to more generally as river herring, alewives occupy an important ecological and economic niche in the state. They are eaten by many fish and bird species, including eagles, osprey and the relatively few Atlantic salmon that still return to Maine rivers. Lobstermen use river herring as bait, and a healthy alewife population is considered key to rebuilding the region’s cod and other groundfish stocks.

While East Coast alewife populations are down significantly, Maine still sees several sizable runs of alewives during the spring spawn. Nearly 2.4 million were counted at the Sebasticook River’s Benton Falls fish trap last year. Alewife returns on other Maine rivers included: 150,660 in the Union River in Ellsworth, 187,429 at the Penobscot River’s fish lift in Milford and 59,960 at the Androscoggin River dam in Brunswick.

DAM PASSAGES AND SPAWNING

The 27,036 alewives counted at the St. Croix’s Milltown Dam located below Grand Falls is a fraction of the estimated 2.6 million alewives that were spawning in the river during the mid-1980s, after fish passage was provided around dams that had blocked alewives for more than a century. Concerned about a dramatic collapse in the bass fishery in nearby Spednik Lake, sportsmen and local officials convinced state lawmakers to once again block alewives at the St. Croix’s Woodland and Grand Falls dams in 1995.

And that’s the way things remained until 2008, when lawmakers, in a compromise criticized by both sides, ordered the state to allow alewife passage around the Woodland dam following a heated legislative debate that drew hundreds to Augusta.

Four years later, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency ordered Maine to allow alewives to pass upstream of Grand Falls on grounds that the barriers violated the Clean Water Act and EPA regulations. In 2013, the Legislature passed L.D. 72, a bill to remove the barriers at Grand Falls.

As in past years, the two sides likely will argue over whether the fish historically inhabited the St. Croix’s upper watershed or whether Grand Falls served as a natural barrier to alewives, who migrate in large schools and do not have the leaping abilities of Atlantic salmon. Opponents of the bill to re-erect the fish barriers also will point out that alewives and bass co-exist in other Maine watersheds, most notably in Washington County’s Meddybemps Lake and in the Damariscotta area, which has both large alewife runs and a thriving bass fishery.

“There is nothing that has changed scientifically with respect to the reasons why the EPA and the state came to the conclusion a couple of years ago that passage of alewives on the St. Croix is both required by law and critical to the ecosystem,” said Sean Mahoney, an attorney with the Conservation Law Foundation, which sued Maine in 2012 to reopen the St. Croix to the fish.

INTRODUCING NEW EVIDENCE

The sponsor of the current bill, Republican Rep. Beth Turner of Burlington, could not be reached for comment Friday. But supporters plan to introduce what they say is new evidence that alewives did not historically occupy the upper river watershed and that, contrary to previous assertions, the 1980s collapse of the Spednik Lake bass populations was not due to a dam operator’s untimely lowering of lake levels.

Greg Dorr, a Bangor-based attorney who is a member of the Grand Lake Stream Guides Association, also argued Friday that re-introducing alewives into the St. Croix could affect the characteristics of a river that has the state’s highest water quality classification.

“Alewives may have ascended the river before, but not the entire basin, and that is what we are trying to impress upon people, that its impact will be felt in an area where it had not been before,” Dorr said.

In 2013, Gov. Paul LePage allowed the bill reopening the St. Croix to alewives to become law without his signature. Interested parties on both sides are now eager to find out where the administration will stand on the bill and whether state biologists will testify during the public hearing. As of Friday, DMR officials weren’t saying.

“We have no comment (on the bill) at this point,” DMR spokesman Jeff Nichols said. “We are going to let the conversation move through the Legislature.”

Both sides are gearing up for the legislative fight.

Cataldo, the guide and Grand Lake Stream selectman, said supporters are placing ads in newspapers to let people know about the upcoming hearing in order to organize a strong showing. Bisulca, who is working with the Passamaquoddy tribal members, said the whole affair “seems like a waste of resources and time” given the 2013 law, but that he expects representatives from Maine and Canada to testify before lawmakers.

“We have three Passamaquoddy communities that sit right there in the watershed,” Bisulca said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.