Elizabeth Atterbury’s exhibition is the Colby College Museum of Art’s seventh installment of its “currents” series. It’s an elegant show of Noguchi-esque sculptures and photos thoroughly steeped in the similar aesthetic of 1950s American photography and pre-war abstract formalism.

Handsome and nicely installed, it’s an easy show to see. Because the Portland-based Atterbury has a great eye for form, design and monochromatic composition, just looking at the show is the best way to appreciate it. I enjoyed it immensely the first three times I saw it because I wasn’t trying to parse or explain the work.

Atterbury’s work became less comfortable when I set out to see the work in the artist’s and museum’s stated terms.

Atterbury’s imagery tends towards geometrical abstraction along the lines of Isamu Noguchi, Constantin Brancusi (whose “Endless Column” is fundamental to the show’s imagery), Man Ray, Jean Arp and other comfortably recognizable mid-century modernists.

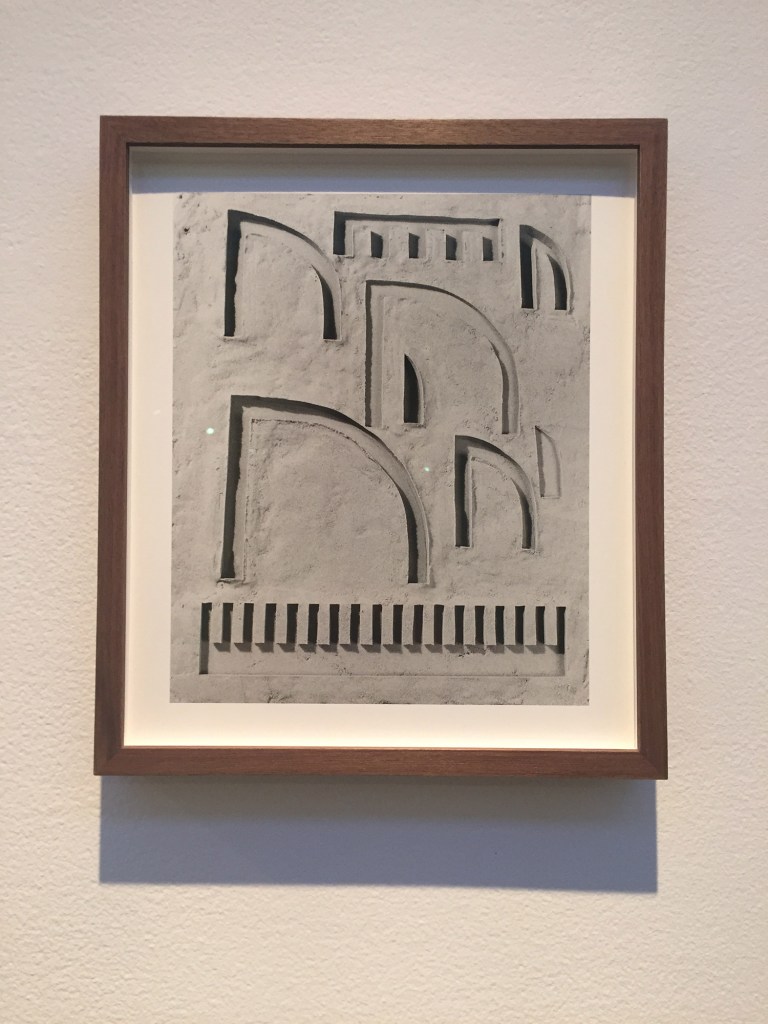

This imagery appears both in her sculptural objects and her photographs of temporary tableaux she stages in ephemeral materials like sand, clay and foam.

This style of modernist imagery is clean, rhythmic and generally looks like the organic geometry of microscope slides: straight-on views of textured systems (rather than objects in landscapes or architectural spaces).

Atterbury’s use of black and white photos and monochromatic objects reinforces the midcentury feel of their forms – superbly clear and anesthetically clean. (I picture them being handled by men in white lab coats, horn-rim glasses, clipboards and perfect posture.)

Atterbury’s objects reveal her concerted senses of rhythm, process, precision and finish. And her craftsmanship is hardly the perfunctory stuff of typical conceptualism with its goal of spilling the banks of form into the realm of language.

Instead, Atterbury’s clear references are to Western abstract art.

And that is where things get weird and problematic.

Atterbury’s intentions, inspirations and aspirations as laid out by Colby curator Diana Tuite in the fascinating exhibition catalog tell the story of a relic included with the show (oddly and uncomfortably placed at the show’s exit). In short, Atterbury’s maternal great-great-grandfather decoded the long lost language of Chinese oracle bones used to predict the future. One of these bones is part of the show and Tuite’s essay explains how the exhibition’s main event – a giant black steel and plywood sculpture dominating the entrance to the show – was inspired by the stone well into which her antiquarian ancestor leapt to his death. The title of the work is simply “Well.”

And sometimes it’s best to leave well enough alone.

“Well” is essentially a giant flat sheet tilted up from the floor that has Arp-like curves cut into it with the cutouts folded back. It’s painted solid black in that midcentury style championed by Louise Nevelson.

You can justify “Well” with the story, but it’s a red herring from the design (form free of language) and art historical (photos as the enduring vehicle of art) content of “currents7.”

Tuite’s essay leaps into the symbolic realm of museological subtlety without addressing the fundamental question of “what’s it to us?”

It becomes apparent that Atterbury’s inspirations are thoughtful, cultural and subtle. But what role does an artist’s inspiration play for the viewer? Fuel, after all, is not the vehicle. What if, for example, the artist makes paintings to put bread on the table? Does that make commercialism its content or merely its historical context? “Why?” matters, but when it comes to public culture – like art – the “why” that matters is “Why should we spend our time with this work – and what’s in it for us?”

Tuite’s essay complicates this question. Or, rather, Atterbury’s stated inspirations muddle it. In the end, it seemed their conversation remained largely amongst intentions – the stuff that led to Atterbury’s making the work – but didn’t wrap its head around what Atterbury expects the audience to take away from seeing it.

This wouldn’t be such a problem if Tuite’s essay didn’t make the work harder to see. It raises a growing question for Maine art: How can we talk about contemporary painting and sculpture in Maine and to what extent does this discourse dovetail with, or diverge from, how we should talk about it?

It seems Tuite and Atterbury want to convey the artist’s mixed Asian heritage and her identity as a woman – deeply worthy themes. In this light, it makes sense to see Noguchi (whom I believe has caught up to David Smith as the leading inspiration for contemporary American sculpture) all through the show: He is the leading source for Atterbury’s aesthetic. And despite his success as an artist and designer, Noguchi was caught between the worlds of Japan and this nation, both in terms of his identity and his cultural proclivities.

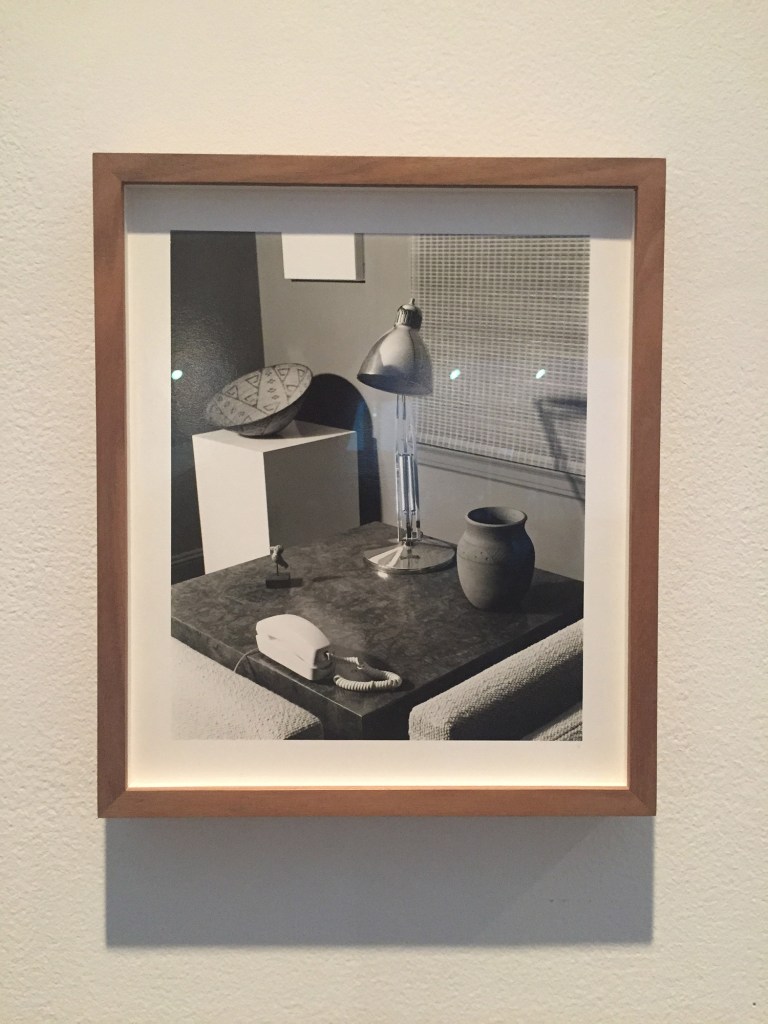

But Atterbury’s work doesn’t interrogate identity other than in the most oblique terms. A couple of photos of midcentury interiors, for example, won’t be enough to raise Noguchi, let alone explain him.

Atterbury is more direct with a fascinating wall installation that reads as sculpture from one side of a wall and as a set of shelves from the other – a savvy positive/negative gesture apt for the architectural language of the show. The shape is a Chinese character from the artist’s mother’s maiden name – not something many Mainers will recognize without the sea-anchor of explanation.

And if you do catch the form’s glyph reference, it leads you away from the satisfying thrust of the show that puts the forms into play as recognizable – not as words or symbols, but as abstract forms echoing the styles of important artists. Those works are not present, but the photos of things that look like them stir the soups of our sensibilities. (It’s that Proustian madeleine: Taste can defibrillate memory.)

What saved the found-then-lost exhibition for me was the catalog’s brilliant little essay by Daniel Fuller in which he avoids directly discussing Atterbury’s work in place of a short meditation about “tumbleweaves” – bits of hair extensions sported and then lost by tough girls on the streets of South Philly and then sighted as a style of detritus.

Fuller elicits the experience of your own fascinated gaze as you absentmindedly transfix on incidental patterns like window blinds or shapes in the sand and so on. He implies we all have found abstractions to which we are particular (one of mine is street light shadows on the bedroom ceiling). By helping us relate to Atterbury’s subjectivity, Fuller helps us empathize with her formalist content rather than be pushed away by the narrative of her unusual personal history.

Unlike the “twice-dead” oracle bone, Fuller’s story of the twice-dead hair is about cultural traces that cannot be deciphered. Instead, the body of traces becomes its own cultural form – not unlike the “language” of midcentury abstract art. Fuller’s insight about how style creeps into culture is profound and it is a far better path to understanding why Atterbury’s works are so powerful when shown together.

Atterbury brings us to the idea of art as artifact. For critics and the public, it’s fundamental: I don’t put stock in artists’ stated intentions because I want to use my own subjectivity instead of borrowing someone else’s. But artists generally can’t – and don’t want to – disconnect from their own work. For them, even though it’s shaped like Zeno’s Paradox (each step gets halfway closer thus never reaching), it’s an eternal postponement of the artifact that they would always want to somehow lead back to themselves.

It’s an elegant model of cultural memory, but it’s a paradox nonetheless.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.