In the early 1970s, Maine’s long-neglected Public Reserved Lands became a heated public issue. After extended public hearings by a Joint Select Committee of its members, a Republican Legislature took these lands from the hands of the Maine Forest Service and entrusted them to a new bureau within the Department of Conservation, to be managed under the principles of sustained multiple use for the benefit of all Maine people. Today, after a surprise move by the LePage administration, the controversy is back on the front pages.

Most of the timberland managed by today’s Bureau of Parks and Lands is Maine Public Reserved Land. Created in 1820 by the Maine Constitution, these are trust lands held in perpetuity by the state for the benefit of all Maine people. Trust purposes include resource conservation (including plants and wildlife), public recreation and the supply of materials for Maine’s economy. Any revenue also must be used for trust purposes. It will require the most careful deliberation to discern these abiding purposes on behalf of all Maine people.

The administration’s proposal – to use some revenue for loans to homeowners to promote the use of wood heat – is a goal some might share. Is this a proper trust purpose? If it is, where, then, lies the line that distinguishes trust purposes from impermissible uses of these funds? Might they be used to relieve local taxpayers of the burden of General Assistance? To fix the fiscal mess in public higher education? To fix the potholes from a fierce winter? This is just one of the many thorny questions before the Legislature today.

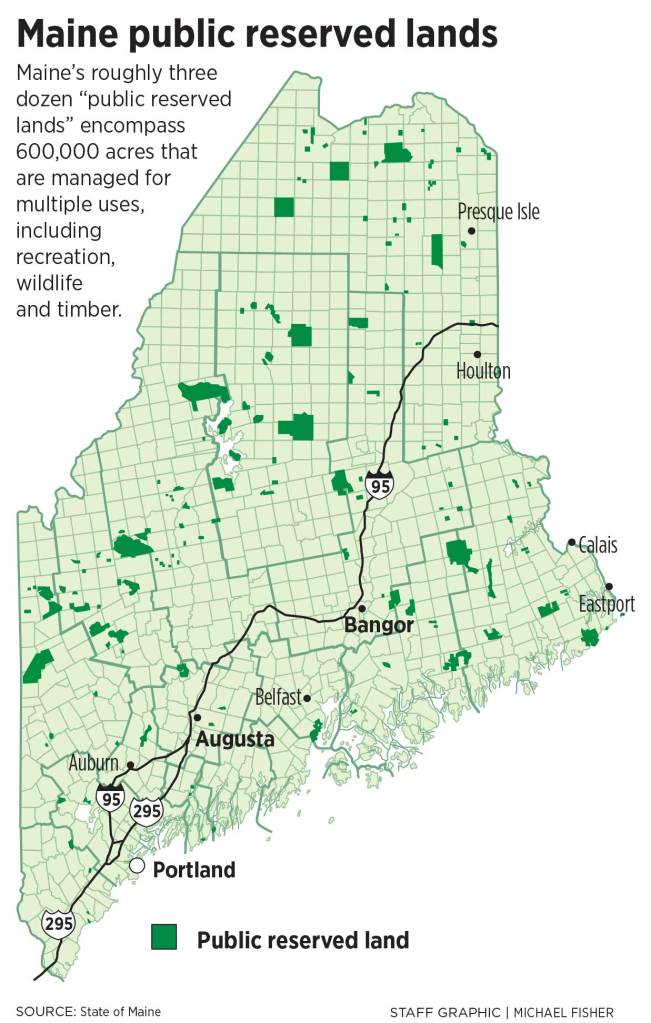

A first question is how much timber should now be cut on the Public Reserved Lands. The bureau manages 600,000 acres of land, of which some 400,000 are available for active forest management. Its enabling statute requires exemplary multiple-use and not revenue-maximizing management. Its goal is to manage a forest distinctively more mature and varied in condition than would an industrial landowner or private investor who pays taxes and earns profits. This it has done from the very start, with widely praised results. Maine’s forests badly need some places that are managed to hold distinctively larger trees and more abundant, natural conditions.

In estimating sustainable harvest volumes, many questions are asked: What is the forest’s condition now, what is its desired future condition and how will it change under alternative methods of management and different levels of cutting? Complex computer models generate alternative strategies and plans. The result is termed an Annual Allowable Cut, or AAC, an amount estimated to be sustainable over time. The AAC is customarily applied as a 10-year, or decadal, total, recognizing that with the ups and downs in wood markets, some years will fall short of the average and others will exceed it.

Harvests were low in the mid-2000s when lumber markets were devastated by the 2005-09 housing crash. A market rebound has enabled the bureau to bring its harvest into the range of its previously planned AAC and, briefly, to exceed it. Compared with the then-applicable AAC of 115,000 cords, the cumulative shortfall in 2005-12 was equal to a full year of allowable cut. Charges today of the bureau’s “overcutting,” based on a single year’s harvesting, are simply misinformed.

The oncoming spruce budworm outbreak has been noted as a reason to increase the cut now. But much of the fir, the most vulnerable species, is small in size and highly scattered. Uncertainty remains as to when the outbreak will arrive, how widespread it will be and how it will affect our forests. It would be reasonable to decide that fir in high-risk areas and stands will be harvested promptly when feasible and the volumes not charged against the current AAC.

A second question is how any surplus public lands revenue might best be used. Under its existing legislative mandate, the bureau has used its revenue stream wisely and well. There has been little public discussion about how surplus revenue might best be applied because any surpluses have been meager at best. Planning, management, road construction and other necessary activities have consumed most of the revenue over the years. Today, there is a surplus in the bureau’s accounts as the result of sound management practices.

Revenue from trust assets must be used for trust purposes and not for whatever use beguiles at the moment. Is the current proposal to promote wood heat a proper trust purpose or not? If there are unmet needs for outdoor recreation in Maine, might this be a more suitable application of surplus funds? Or may such expenditures be made only on the Public Reserved Lands themselves? Or might they apply to public investment in outdoor civic spaces in our downtowns, such as walking trails, canoe put-ins and scenic river overlooks and gathering spaces and so contribute to Maine’s quality of place?

Some might be concerned, in addition, that making these revenues available for non-trust purposes will create incentives for cutting too much wood on our lands; or in ways not fully consistent with the bureau’s long-standing, multiple-use mandate. Others might worry about creating a fiscal “use it or lose it” mentality within the department that results in unnecessary and even unwise expenditures – the very opposite condition from the stinginess with which the Public Reserved Lands were unmanaged prior to the 1970s. So, again, this question has no ready answer.

The Maine Legislature must take care, then, to answer some very large and thorny questions before changing longstanding policy. Among others, these include:

• Do we have too much or even enough public land in Maine?

• Should we be cutting more timber on the state’s Public Reserved Lands?

• How might any revenue surpluses from these sales best be applied?

• Should forest condition goals on the Public Reserved Lands be made more specific?

• Would these lands be better managed if the Bureau were merged into the Maine Forest Service, as proposed?

None of these questions has an easy answer or needs be resolved within the next month. Everyone needs now to take a deep breath and give thoughtful deliberation to these important and complex matters underlying long-term public policy and land management decision-making. After more than a generation since their original formulation, they deserve the most careful, considered and open public dialogue.

The best vehicle for this would be a new Joint Select Committee of the Legislature to study the issues and report back to the next session of the Legislature. This device has a long history of wise use in Maine – from those to consider “The Northeastern Boundary of the State” in 1828, to “The Conditions of Affairs in the Late Insurrectionary States” in 1872, to The Irregularities and Changes in Election Returns” in 1880, to “Maine’s Workforce and Economic Future” in 2012.

Each of these important committees was charged thoughtfully and thoroughly to study the issue and to return to the Legislature with careful findings and recommendations. Surely, for a public trust established at the time of Maine’s creation as a state, nothing less is warranted now.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.