Lou Ureneck picked the book from his uncle’s shelf at random. “It had a red cover,” he said. “I think that drew my attention.”

It was “The Smyrna Affair” by Marjorie Hoosepian Dobkin, an account of the 1922 destruction of the Turkish city Smyrna, the death of a half-million people and the events leading up to it. Tucked deep within the book was the story of Asa Jennings, an American man of religion and principle who saved another million from death with an unlikely rescue mission.

As Ureneck read the story of Jennings, he knew he had the foundation of a much larger book, a real-life adventure story that involved daring, cunning and heroics, and the devastation of the richest city of the Ottoman Empire. “I carried the idea around in my head for years,” Ureneck said. “I even consulted with a screenwriter. I asked, ‘Could we turn this into a movie?'”

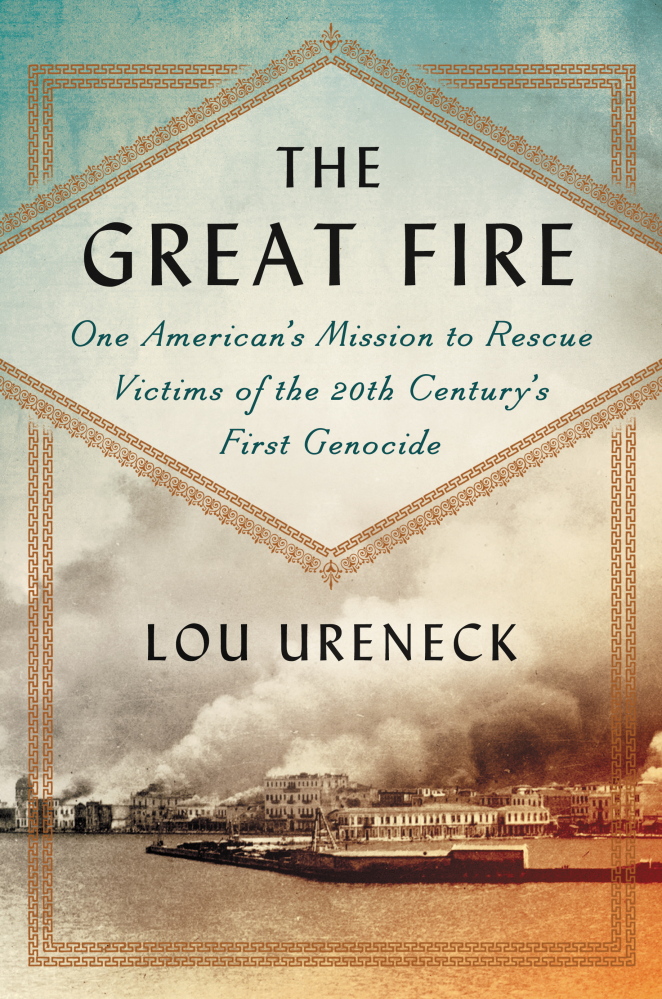

They probably could, but Ureneck decided to write a book instead. A journalist and former executive editor of the Portland Press Herald/Maine Sunday Telegram, Ureneck returned to his reporting and storytelling days with “The Great Fire: One American’s Mission to Rescue Victims of the 20th Century’s First Genocide.”

It is his third book. The first two were memoirs. “I have a third memoir that I want to write, centered on my mother. But I wanted to try something different, and re-engage my reporting and journalism skills. This book gave me the perfect opportunity to do that.”

Since leaving the Press Herald in 1996, Ureneck worked as deputy managing editor of the Philadelphia Inquirer. He teaches journalism at Boston University.

He’ll return to Portland mid-May to discuss his book at the Portland Public Library.

Q: Asa Jennings acted heroically. Describe how his character was defined by the actions that he took to lead this rescue effort.

A: Jennings was steeped in two traditions: religious faith and service. The social gospel of American Protestantism of the late-19th and early-20th centuries shaped his attitudes. His health was poor, and he deferred to the authority of others at Smyrna until that important day — Sept. 20 — when he decided to act on his own to initiate an evacuation of the refugees at Smyrna. My impression is that it was a case of powerful personal empathy confronting enormous suffering.

Q: imagine there was a reasonable amount of information available, and some photos. You also traveled quite a bit. Was it an adventure?

A: It was an astonishing adventure. I drew from about 20 libraries and archives in five countries. I traveled four times to Greece and Turkey and walked the streets and Quay of Izmir (the modern Smyrna) with old maps and photographs. I traveled to the high plateau of the Anatolian interior and ascended the mountain from which the Turkish nationalist offensive began and had a Turkish army officer guide me through a key battlefield. It turned out that most of the best information was in Washington because the U.S. had five destroyers at Smyrna, and each of the commanders wrote detailed reports. I spent many fruitful and satisfying hours at the National Archives. I also was able to get access to the personal papers of key characters in the story. This gave the research a personal turn.

Q: What is Turkey like?

A: It’s a beautiful landscape, the most beautiful landscape I ever experienced. The view of the Aegean from the peninsula south of Smyrna will bring tears to your eyes — the blues and yellows, the islands, the Mediterranean sky. I should also say Turkey is not Europe. It’s not the West. I felt it immediately. Many Turkish people helped me with my research, but they live in a country that does not tolerate dissent. Once a secular nation, Turkey more and more is bringing Islam into government and the public space. The Turkish people are not familiar, as far as I could see, with this period of their history except as it has been shaped by the official ideology.

Q: How familiar with this story were you before beginning your research? Has it consumed you for years?

A: I knew a little, not much really. I spent four years researching and writing the book. Often it was difficult for me to emerge from the time period and the story to do my other work, which is to teach. It was all-consuming.

Q: You make the point in the book, if I understand it correctly, that this slaughter marked the first use of the word “genocide.” It truly was an indicator of what was to come, and as such should be an event we are familiar with. And yet, the story of Smyrna is most forgotten. Why?

A: The religious cleansing that swept Turkey for 10 years began in 1912. The cause was the paranoia among the Ottoman elite about the future of the empire and nostalgia for its glorious past. Christians became scapegoats as the Ottoman Empire declined, and Christian peoples including Armenians, Greeks and Assyrians were slaughtered to create a “Turkey for the Turks.” It’s surprising that the story faded because American had such a big stake in Turkey at the time. America was especially sympathetic with the suffering of Armenians. One reason the story faded was because the U.S. State Department was eager to build a diplomatic and commercial relationship with the Republic of Turkey, and memory of the genocide stood in the way of that. It sought to downplay what had happened to open a new era in U.S.-Turkish relations.

Q: As I began reading, I picked up on the lessons that apply to our times today. What should we have learned from this, and what can we still learn?

A: Asa Jennings offers the lesson that one person can make a difference. He save hundreds of thousands of lives.

Q: What is your next project?

A: I’m now searching for it.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.