Portland Sea Dogs outfielder Blake Tekotte walked from the on-deck circle toward home plate. He looked toward the third-base coach for a sign and stepped into the batter’s box, getting one foot set, then both.

“Strike one!”

Huh?

Before seeing one pitch, Tekotte fell behind in the count 0-and-1 because the large digital timer – which counts down from 20 seconds between pitches – had dropped below the :05 mark without Tekotte being alert to the pitcher and ready to hit.

“The umpire didn’t give me a warning or anything,” he said. “Just called strike one. I’m trying to worry about hitting a fastball rather than looking at the clock.”

Tekotte was the first member of the Sea Dogs to be penalized under a new initiative at the highest levels of Minor League Baseball. In an effort to speed the pace of play, all 60 Double-A and Triple-A ballparks this season have been outfitted with three prominent digital clocks that count down the seconds between pitches, between innings and between pitching changes.

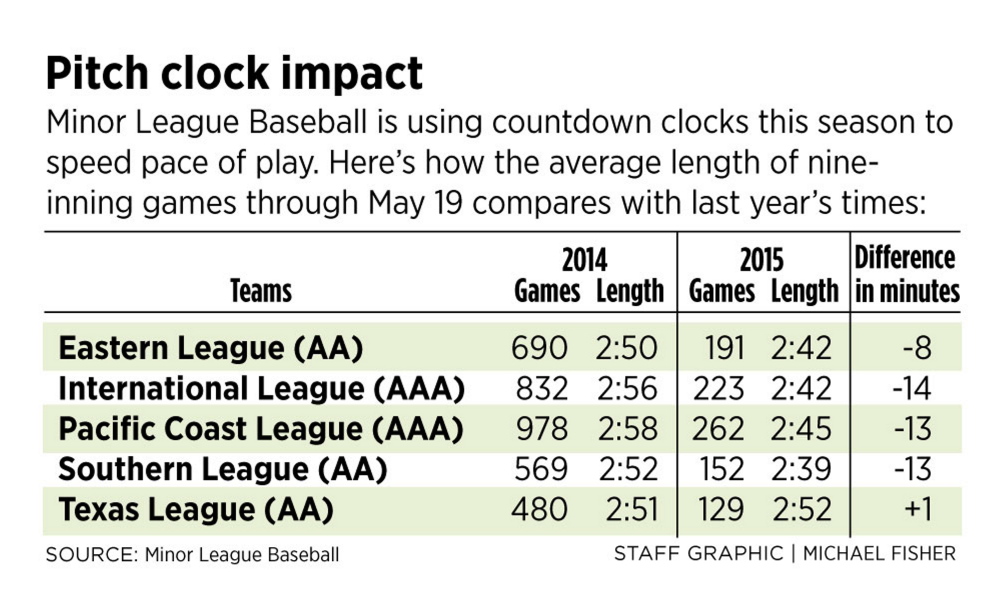

The clocks seem to be having an impact. Nine-inning games in the Double-A Eastern League – in which the Sea Dogs play – are on average eight minutes faster (2 hours, 42 minutes) than last year through Tuesday’s contests. Game times have been shaved further in the Triple-A International League (14 minutes) and Pacific Coast League (13 minutes).

After a grace period in April, batters and pitchers are now being penalized for dawdling. Pitchers must come to a set position before the 20-second clock reaches zero or they’ll be charged with a ball. Batters must be ready to hit with 5 seconds remaining or they’ll be charged with a strike.

They aren’t the only ones suddenly faced with deadlines. After the last out of an inning, the timers count down from 2:25. When the clock reaches 35 seconds, the catcher should be throwing down to second base to complete warm-ups. And the home team’s staff must complete all promotions and entertainment such that the next batter can be announced when the clock reaches 0:25. Promotions that run over their allotted time are not penalized, but umpires are encouraged to file reports on habitual offenders and the league can issue fines.

“We pride ourselves in being able to get our on-field promotions on and off in 90 seconds,” said Jim Heffley, the Sea Dogs vice president in charge of game operations. “Our focus is the game. We don’t want to disrupt that any more than we do.”

Relief pitchers are allotted 2:25 from the time they step on the warning track, so if they’re quick, they can take more than the traditional eight warm-up tosses.

UNOBTRUSIVE, OR CHANGING GAME?

Improving the pace of play is high on the agenda of new Major League Baseball Commissioner Rob Manfred. The average length of big league games reached an all-time high of 3:02 in 2014 despite a decline in scoring. Replay challenges had a lot to do with that, but still, the average time had crept up from 2:33 in 1981 to 2:59 in 2013.

“I understand they want to speed the game up,” Tekotte said. “But they’re trying to change the game of baseball and it was fine the way it has been.”

The players union would have to agree to any changes at the major league level, which is why the clocks are being tested this season in the high minors, where players are not unionized. However, the same clocks have been installed at major league parks, with warning letters for violators instead of ball-strike penalties, a policy resulting in an average length below 2:54 for nine-inning games through Sunday.

“We are very pleased by the results of this year’s expanded pace of game program and grateful for the cooperation we have received from players,” said Mike Teevan, vice president of communications for MLB. “We believe the overall pace of game is crisper and more streamlined through the sensible and unobtrusive steps we have taken.”

SEA DOGS BUCKING THE TREND

On May 1, Eastern League umpires began penalizing batters and pitchers for violations. Through Tuesday’s games, nine batters have been issued strikes (including Tekotte and Sea Dogs first baseman Jantzen Witte on Friday night) and six pitchers have had balls added to the count.

“I’m not a big fan of things that take away from this game that’s been around for 150 years,” said Billy McMillon, in his second season as Portland’s manager. “I can’t believe that this is going to shave off a significant amount of time in games. What makes games quicker is pitchers throwing strikes and playing clean in the field.”

McMillon’s perception is correct. The Sea Dogs are taking nine minutes longer to complete games this season than in 2014, and – at 2:55 – rank slowest among the 12 Eastern League teams.

There are a few reasons for that. Portland enjoyed superior pitching and defense last season and won 64 percent of home games, thus eliminating a turn at bat in the bottom of the ninth inning. This year’s club is allowing unearned runs at more than twice last year’s rate (.74 per game versus .36) and winning only 35 percent of its home games. Total runs per game (scored by both teams) in Sea Dogs games are up to 9.58 from 8.24 a year ago.

SOME FANS LIKE THE SPEED-UP

The current Sea Dogs homestand is the second with umpires enforcing clock violations. Matt and Jennifer Shadrick, visiting Hadlock from Hingham, Massachusetts, earlier this month with sons Ben, 14, and Will, 11, said they like the idea. Matt said baseball has lost some of its luster because of the length of games.

“Four hours is a big chunk of time to spend at a sporting event,” Jennifer said. “I am all for the clock. Can they throw it down to Little League, too?”

Mike LaViolette, 50, of Scarborough, has been a season-ticket holder since the Sea Dogs’ first season in 1994. He said the timers act as deterrents, similar to a police car parked on the side of the road.

“That’s what it reminds me of,” he said from a seat behind the visiting dugout. “These guys see the clock and they stay in the box.”

Then again, he said his girlfriend finds the clock distracting, often watching it instead of the game.

Ryan Clark, chief of the three-man umpire crew that worked at Hadlock earlier this month, said he keeps a mental clock in his head and only glances at the digital clock when a player seems to be taking a lot of time.

“It does give us other things to think about,” he said. “It’s no longer ball-strike-safe-out. Plus, it’s new, so you think about it more.”

PLAYERS HOPE CLOCK GOES AWAY

Sea Dogs pitcher Madison Younginer experienced the clock earlier than most of his teammates while playing in the Arizona Fall League last year. Younginer, who has a copy of Thoreau’s “Walden” on his nightstand, is not thrilled with the introduction of a digital clock to a pastoral game.

“You look over and see a baseball scene. You see grass. You see fence. You see fielders. You see people,” he said. “And now you’ve got a clock there. You see a digital clock that stands out.”

He paused.

“It doesn’t belong.”

Tekotte said hitting is hard enough without having to worry about a clock.

“I mean, 70 percent of the time we’re failing anyway, and that’s being really good at this game,” he said. “And now we have to worry about a shock clock, or whatever you want to call it? It’s unneeded. Hopefully, it goes away.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.