WASHINGTON — Elfriede Rinkel’s past as a Nazi concentration camp guard didn’t keep her from collecting nearly $120,000 in American Social Security benefits.

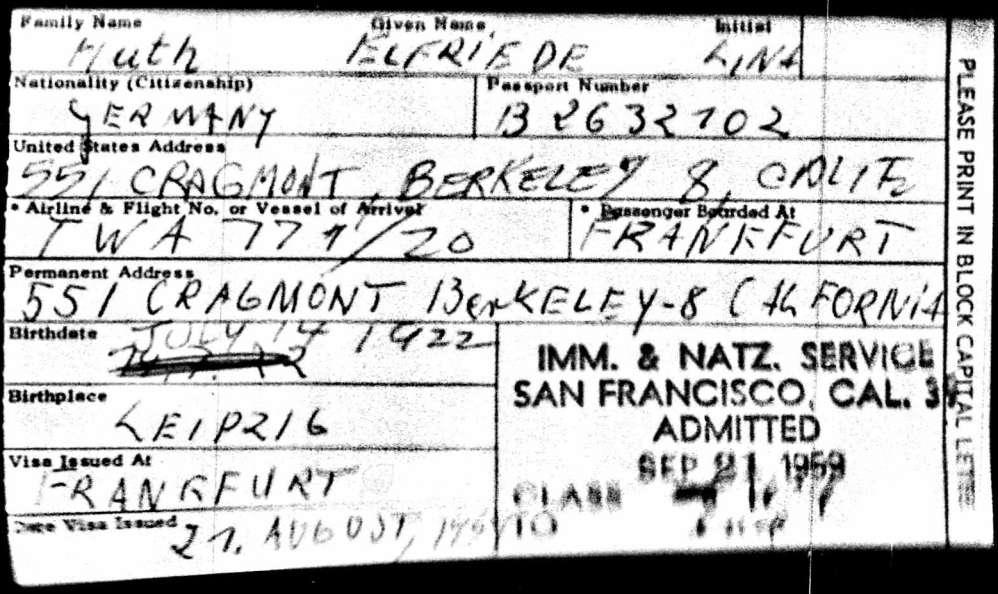

Rinkel admitted to being stationed at the Ravensbrueck camp during World War II, where she worked with an attack dog trained by the SS, according to U.S. Justice Department records. She immigrated to California and married a German-born Jew whose parents had been killed in the Holocaust.

She agreed to leave the United States in 2006 and remains the only woman the Justice Department’s Nazi-hunting unit ever initiated deportation proceedings against. Yet after Rinkel departed, the Social Security Administration kept paying her widow benefits, which began after her husband died, because there was no legal basis for stopping them until late last year.

Rinkel is among 133 suspected Nazi war criminals, SS guards, and others that may have participated in the Third Reich’s atrocities who received $20.2 million in Social Security benefits, according to a report to be released this week by the inspector general of the Social Security Administration.

The payments are far greater than previously estimated and occurred between February 1962 and January 2015, when a new law called the No Social Security for Nazis Act kicked in and ended retirement payments for four beneficiaries.

The report does not include the names of any Nazi suspects who received benefits. But the descriptions of several of the beneficiaries match legal records detailing Rinkel’s case and others.

The large amount of the benefits and their duration illustrate how unaware the American public was of the influx of Nazi persecutors into the United States, with estimates ranging as high as 10,000. Many lied about their Nazi pasts to get into the United States and even became American citizens. They got jobs and said little about what they did during the war.

Americans were shocked in the 1970s to learn their former enemies were living next door. Yet the United States was slow to react. It wasn’t until 1979 that a special Nazi-hunting unit, the Office of Special Investigations, was created within the Justice Department.

Rep. Carolyn Maloney, D-N.Y., asked that the Social Security Administration’s inspector general look into the scope of the payments after an Associated Press investigation was published in October 2014.

AP found that the Justice Department used a legal loophole to persuade Nazi suspects to leave the United States in exchange for Social Security benefits. If they agreed to go voluntarily, or simply fled the country before being deported, they could keep their benefits.

The Justice Department denied using Social Security payments as a way to expel former Nazis.

By March 1999, 28 suspected Nazi criminals had collected $1.5 million in Social Security payments after their removal from the United States, Social Security Administration records showed.

Since then, AP estimated the amount paid out had grown substantially. That estimate was based on the number of suspects who qualified and the three decades that have passed since the first former Nazis, Arthur Rudolph and John Avdzej, signed agreements that required them to leave the country but ensured their benefits would continue.

Maloney said the IG’s report showed that dozens of alleged and confirmed Nazis actively worked to conceal their true identities from the U.S. government and still received Social Security payments.

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.