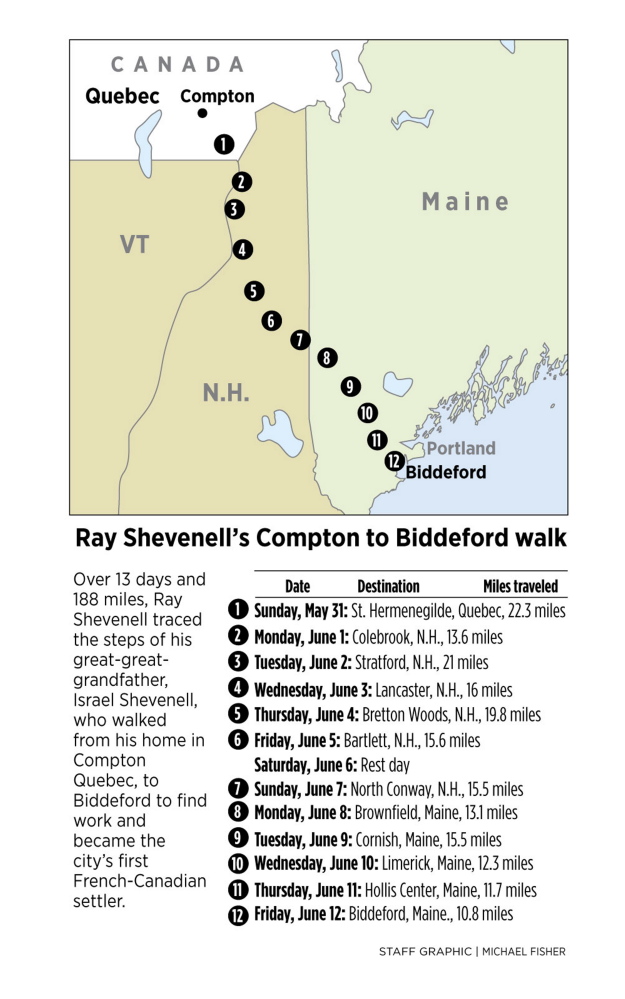

BIDDEFORD — Ray Shevenell set out from Hollis Center on Friday morning on the last leg of his 188-mile trek from Compton, Quebec.

“This is the very first day my feet don’t hurt,” the 74-year-old said when he was about a mile-and-a-half from his destination, Shevenell Park in Biddeford, named for the great-great-grandfather who took the same journey 170 years earlier.

Israel Shevenell, recognized as the city’s first French-Canadian settler, was 19 years old in the spring of 1845 when he left on foot for Biddeford to find work as a bricklayer at the mills being built.

That fall, he walked back to Canada to retrieve his family, who returned with him.

It’s a story that’s stuck with Ray Shevenell since his father told it to him when he was a young boy. When Shevenell turned 50, he got the idea to retrace his ancestor’s steps.

Two years ago, he started training by walking around his neighborhood in Cape Elizabeth and at the South Portland Community Center. He and his daughter, Tonya Shevenell, used old maps to figure out what route their forebear would have taken.

The two left Compton on May 31, she in a car and he on foot, covering 22 miles the first day, almost reaching the U.S. border. He got his first blister nine miles in and has pushed through the pain ever since, taping his feet every morning and changing shoes, depending on where it hurt. For a stretch, he walked with a sneaker on one foot and a sandal on the other.

“It’s an amazing art and science to me how he’s figured out how to make these steps happen,” said his daughter, who filmed the trek for a documentary she’s making about the journey and their family history.

Fueled by lemon-lime Gatorade, bananas, Clif bars and trail mix, Shevenell has walked through downpours, crossed paths with bears, endured temperatures ranging from 38 to 85 degrees and found himself in a 3-foot gap between a tractor-trailer and a rock wall.

That was the only close call. Dressed in neon gear and glued to the left side of the road – what he calls the cardinal rule – Shevenell stayed on high alert at all times, never zoning out or getting bored.

“I’m an in-the-moment person,” he said.

Perhaps the most poignant stretch was the seven miles on a dirt road in New Hampshire that, judging by the old maps, was likely the same one his great-great-grandfather walked.

“I felt really close to him,” he said.

But much of what Shevenell encountered on his journey became emotional. Just seeing the drivers carefully passing him could bring him to tears, he said. He waved to and thanked every driver that passed.

“For protecting me along the way,” he said.

Shevenell has come close enough to death to understand the value of life. At 67, he and his wife were driving to the movies when he started having strange pains. They detoured to the emergency room, where he had back-to-back open heart surgeries that night for an enlarged aorta.

An avid runner, he likely made it through the ordeal because of how fit he was, his daughter said. But, when he came out of it, doctors told him that running – his biggest passion – would no longer be part of his life.

“He never complained and just started walking,” his daughter said.

GOING ALONE AT THE END

At a pace of about 25 minutes per mile, Shevenell walked an average of 16 miles a day for 12 days with one rest day in the middle.

He planned the shortest walk – 10.8 miles – for the last day to give him leeway to catch up, but he didn’t need it.

Shevenell, who returns to work at Unum on Monday, took his time Friday, making his way from Hollis Center to Shevenell Park, stopping to talk to two women having a yard sale in Dayton.

He walked most of the last mile with Richard Horton. The husband of his wife’s cousin, Horton was one of the “trek angels” who met up with Shevenell at various points along the way.

But the final few hundred feet, he insisted on going alone, as his great-great-grandfather did.

Friends and family members waited at Shevenell Park, a wide alleyway off Main Street with tables and chairs and a poster with a picture of Israel Shevenell.

Three minutes before his planned 2 p.m. arrival, Ray Shevenell turned a corner and came into view.

They clapped as he reached the park and stretched out his arms.

Asked if he was tired, he just kept smiling.

“I’m exhilarated,” he said. “I feel I could do this again.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.