BRUNSWICK — The night used to be dark and mysterious, but we’ve tamed it with artificial light, an open-all-night culture and the 24/7 news cycle. If we look out our window at 3 in the morning, chances are we’ll see a TV flickering in a neighbor’s house, a light in the kitchen next door or someone arriving home from the late shift.

This summer, Bowdoin College Museum of Art examines the allure of the dark and the importance of the night in modern art with “Night Vision: Nocturnes in American Art, 1860-1960.” Bowdoin borrowed art from museums across the country, and presents 90 of them in a range of media to show how our perception of the night has changed from the days before electricity to the dawn of the space age. The exhibition demonstrates how the electrification of the American landscape altered our perception of the night and how artists respond to it.

“American artists have digested the night for several generations, and the variety of responses to the night is fascinating to see,” Bowdoin curator Joachim Homann said. “Night changed when electricity arrived, and our perception of night changed along with it. Artists find the night an inspiration and a challenge.”

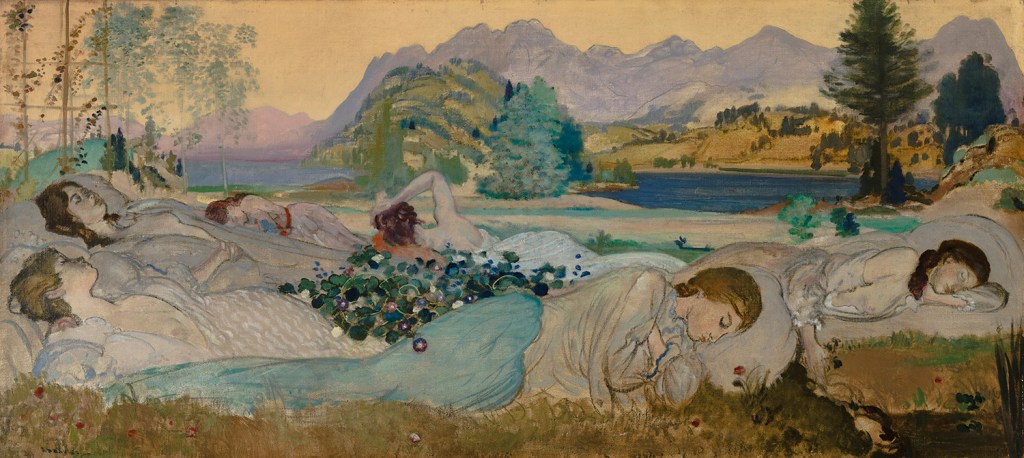

There’s infinite mystery in the night. Artists use the night for reflection and observation. They can hide in the darkness, playing voyeur as they observe from the outside looking in. Some turn inward in search of personal truths.

Bowdoin considers “Night Vision” a noteworthy exhibition because no major museum has examined the topic as comprehensively as Homann and his colleagues are doing this summer, museum co-director Frank H. Goodyear III said. Various artists have received exhibitions about their nighttime work, and there have been small examinations of the subject over time. This one goes deep, he said. Already, in advance of the opening, the show is garnering attention, including from The New York Times and the Wall Street Journal, which highlighted it as a summer must-see.

“It’s an ambitious project and very broad in scope,” Goodyear said. “Almost every major American artist during this 100-year period worked at night and was engaged in the artistic possibilities of working at night.”

Bowdoin borrowed paintings and other art from more than 30 museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, the Phillips Collection, private collectors and other lenders. It opens Saturday and runs into the fall.

The idea stemmed, in part, from the reaction of visitors to two paintings in the Bowdoin collection: Andrew Wyeth’s iconic painting “Night Hauling” from 1944, depicting a lobsterman pulling a trap into a dory in the dark, phosphorescence sparkling in the water and glowing within the trap like a lamp; and Winslow Homer’s “The Fountain at Night.”

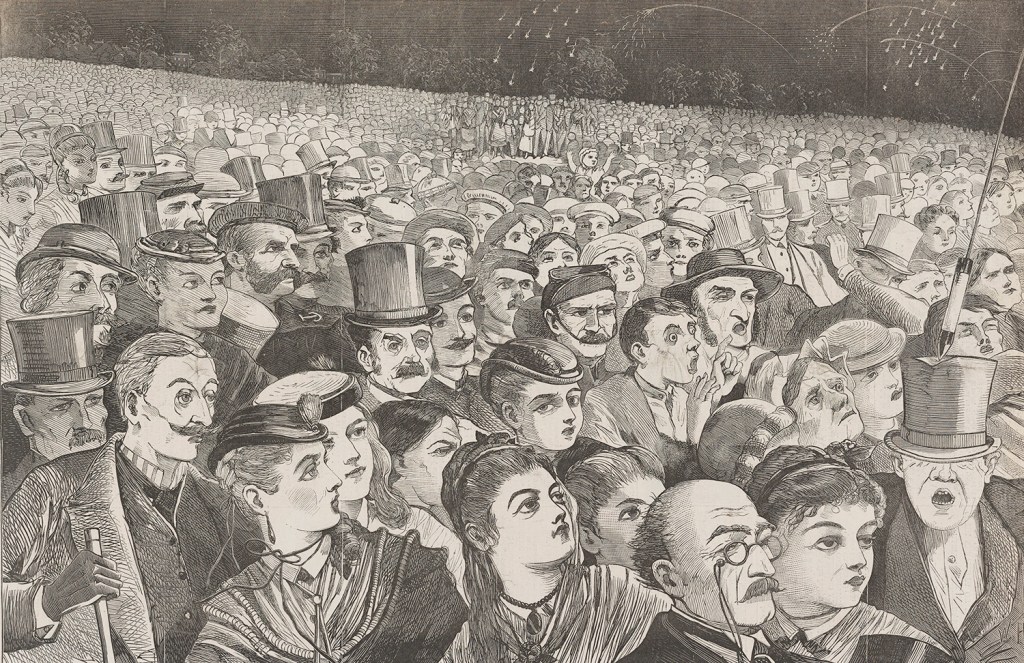

Homer portrays central feature of the Chicago World Fair from 1893, a large fountain and pond traversed by a Venetian gondola. At night, the area was brightly lit and was seen as a dramatic display of electric light.

Visitors love those paintings and express disappointment when they are not on view, Homann said.

The paintings by Homer and Wyeth almost are on opposite poles. Homer responds to a climate of optimism and technical progress, while Wyeth reflects on the mystery of a Maine night on the water and the darkened mood of World War II.

Homann noted that two of the most recognized paintings in the world relate to the night: “Nighthawks” by Edward Hopper and “Starry Night” by Vincent van Gogh. Bowdoin was unable to borrow “Nighthawks” for this show, and van Gogh wasn’t American. “Night Vision” takes a distinctly American view of the night.

Homann promised people will not miss “Nighthawks.” There are other Hoppers in the show, and many of the most famous and accomplished artists are represented, including Frederic Church, George Inness and Georgia O’Keeffe. Many of the big names in Maine are here too: Marsden Hartley, William and Marguerite Zorach, and Andrew Wyeth’s father, N.C. Wyeth.

“Night Vision” presents moonlight reflections on the water, urban street scenes and abstract reflections.

We see Albert Bierstadt’s “The Burning Ship,” from 1869, with a sailing vessel ablaze, the orange glow of fire reflecting on the water as men row toward the catastrophe. There are illustrations by Thomas Nast for Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven” and Homer campfire illustrations from the Civil War.

By the late 1800s, electricity spread across America. Artists responded by capturing the new night – streets illuminated by lamps, trains glowing as they move across the city and jazz musicians performing in nightclubs.

Modernism brought a different perspective. Charles Burchfield’s “The Night Wind,” from 1918, portrays what Homann calls “the unsettling effects” of darkness as clouds and snow overtake a fragile homestead. William Zorach’s “Mirage – Ships at Night” offers an abstracted view of vessels crossing the water, a crescent moon on the horizon.

O’Keeffe’s “New York, Night,” from 1929, signaled the artist’s shift from the natural landscape to urban scenes, mirroring her time in New York City. Like the rest of America, she was fascinated by skyscrapers, which represented American innovation and advancement. She made her painting from her hotel apartment, high above the streets.

These paintings not only presented artists with a different perspective on a familiar subject, but also new technical challenges. This exhibition illustrates how artists responded to the test of representing shadow, light and form. The show makes the case that nighttime painting also fueled experimentation and informed the rise of abstraction.

Photographers took advantage of the night, as well. For the cover of the catalog, Bowdoin reproduces Berenice Abbott’s iconic New York photo, “Midtown Manhattan,” from 1934, showing the skyline from above, lit up like a jewel box. It could be a companion to O’Keeffe’s “New York, Night.”

Ansel Adams’ moon photos, completed over many years, capture the mystery of the orb and its effect on the landscapes below, both visually and psychologically. “Moon and Half Dome,” from 1960, predated mankind’s lunar exploration, but one wonders if the pull of the moon and our desire to reach it wasn’t on the photographer’s mind. The moon hovers overhead like an egg, out of reach but close enough that we want to touch it.

Working on this show has prompted Homann to pay more attention to the night and the moon. He hopes it does the same for others.

“It’s really wonderful to go out and enjoy the moon and enjoy a dark moment,” he said. “Switching off the light is something we should all do more often.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.