It’s hard to predict where David McCullough’s intellectual curiosity and penchant for revealing the humanity of historical figures will lead him next.

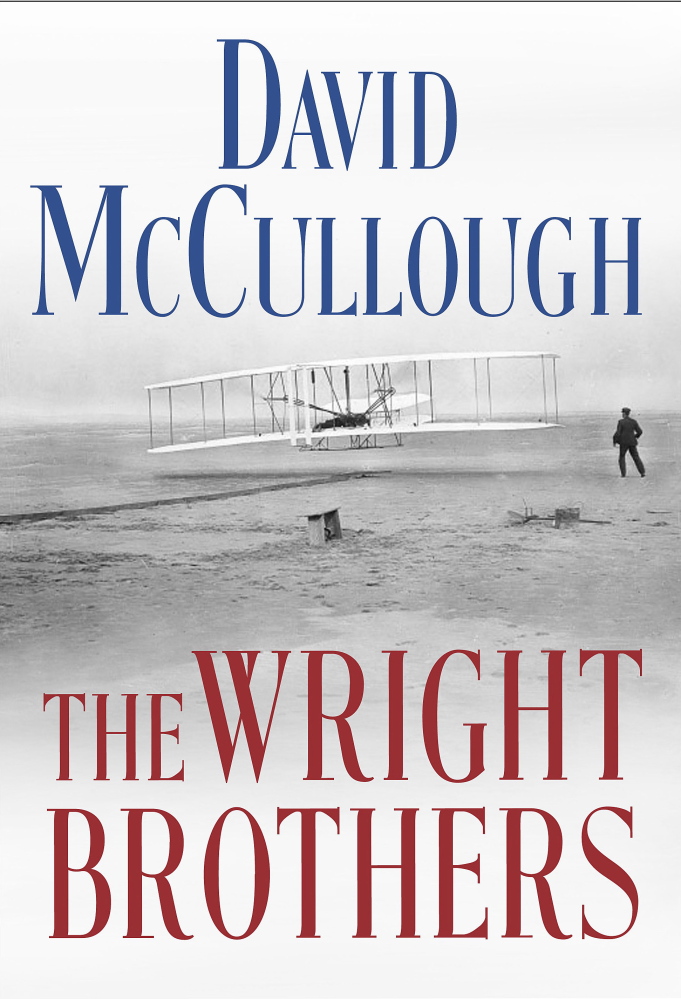

Stories of influential Americans who spent part of their lives in France led to his 2011 book, “The Greater Journey.” While researching that book, a letter written by author Edith Wharton about seeing an “aeroplane” over Paris led McCullough to aviation pioneers Orville and Wilbur Wright and his latest book, “The Wright Brothers.”

McCullough, who spends part of each year at his home in Camden, says research for his book on the Wrights gave him “about eight ideas” for future books, including one that could lead him to delve deeply into the often overlooked state of Ohio.

When the Wrights lived there, “Dayton had more patents per capita than any other (American) city. It was like the Silicon Valley of its time,” said McCullough, 82. “(Thomas) Edison was from Ohio. Neil Armstrong, the first man to walk on the moon, was from Ohio. So many presidents. Don’t underestimate Ohio.”

And don’t underestimate McCullough, probably the best-known historian of his time and still yearning to uncover inspiring stories.

McCullough will be speaking about “The Wright Brothers” at two events this week, both within a short drive of his Camden home. Tuesday he’ll give a lecture at the Camden Opera House, organized by the General Henry Knox Museum in Thomaston. On Saturday he’ll do a book signing at Left Bank Books in Belfast. “The Wright Brothers” came out in May.

McCullough grew up in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and started looking for chances to explore the human side of history at an early age. He remembers as a boy yelling “Johnstown flood” when gravy spilled over his mashed potatoes. As he grew older, he wanted to know more about the flood, which killed more than 2,200 people in western Pennsylvania in 1889. His first historical work, “The Johnstown Flood” was published in 1968.

McCullough majored in English literature at Yale University. He has won two Pulitzer Prizes, for “Truman” and “John Adams.” Other books by McCullough include “1776,” “Mornings on Horseback,” “The Path Between the Seas” and “The Great Bridge.”

He has spent much of his adult life in New England and has a home on Martha’s Vineyard, off Massachusetts. He and his wife, Rosalee, bought a home in Camden more than a decade ago to be near family. Their daughter, author Dorie McCullough Lawson, lives in Rockport with her husband, artist T. Allen Lawson, and their children.

McCullough said that in writing about the Wright brothers, he wanted to go beyond “the five or 10 minutes they talk about in school” and find out more about “what they were like as human beings.” The book of course includes a detailed account of Dec. 17, 1903, when the Wright Flyer became “the first mechanically powered, heavier-than-air machine to achieve controlled, sustained flight with a pilot aboard.” But it goes well beyond that.

Drawing from many personal letters, as well as newspaper accounts, McCullough reveals details that help explain why the Wrights were able to do what they did, not just how they did it. He thinks two of the major reasons were their education and their upbringing.

Though neither of them graduated from high school or went to college, Orville and Wilbur grew up in a house filled with books and basically had a home-based liberal arts education that ranged from Roman literature to natural history and the latest scientific theories.

“They read all the time, from Virgil to Mark Twain to history and natural history. Today, people who have ambitions for a career in science are side-stepping the liberal arts. But they had only a liberal arts education and went on to solve one of the most seemingly impossible technical challenges of all time,” McCullough said.

McCullough said Wilbur was “definitely a genius,” and Orville was innovative mechanically but basically followed his older brother’s lead.

The Wrights were the sons of a strong-minded minister who preached self-reliance and not succumbing to failure. The brothers financed all their own experiments and equipment with money made from their Dayton bicycle shop.

Before they began their experimental flying, some of the other people who had tried to fly had been killed. The Wrights tested gliders and powered machines hundreds of times, with no safety equipment and always knowing they could be killed. Orville was nearly killed during one demonstration flight. An Army officer flying with him died in the crash.

“I think how they handled failure was so important,” McCullough said. “They never lapsed into self-pity. In my book ‘1776,’ (George) Washington makes terrible mistakes, but he learns from them and will not give up. The Wright brothers had that same spirit.”

In delving into the Wrights as people, McCullough writes much about their strong-willed sister, Katharine, who was a schoolteacher and who cared for the two bachelors most of their lives. When the brothers toured Europe to demonstrate and sell their plane, around 1908 and 1909, Katharine was with them and became a favorite subject of European newspaper men. Wilbur, who wore the same dark suit and had the same demeanor whether meeting mechanics or royalty, was “adored” by the French people for being “so American,” McCullough said.

Wilbur died of typhoid fever soon after he achieved fame, in 1912 at the age of 45. Orville died in 1948, at the age of 77.

McCullough, in his research, uncovered that Wilbur had suffered an injury when he was about 18 that changed the course of his life, and perhaps history. Wilbur was hit in the face with a hockey stick. The hockey stick was wielded by a young man who later killed his parents and several other people. Wilbur suffered great pain in his face and jaw for months and started to withdraw from society. Before the accident, he had dreamed of attending Yale and becoming a teacher. But while recuperating, he read and was a recluse at home for several years. He read from an incredibly wide range of books kept in the Wright home, McCullough said. And that reading helped spur a curiosity in birds and flight that would fuel his life’s work.

“Writing this book made me realize that how someone is raised, at home, is more important than we tend to understand,” said McCullough. “And we need to know more about it.”

Copy the Story Link

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.