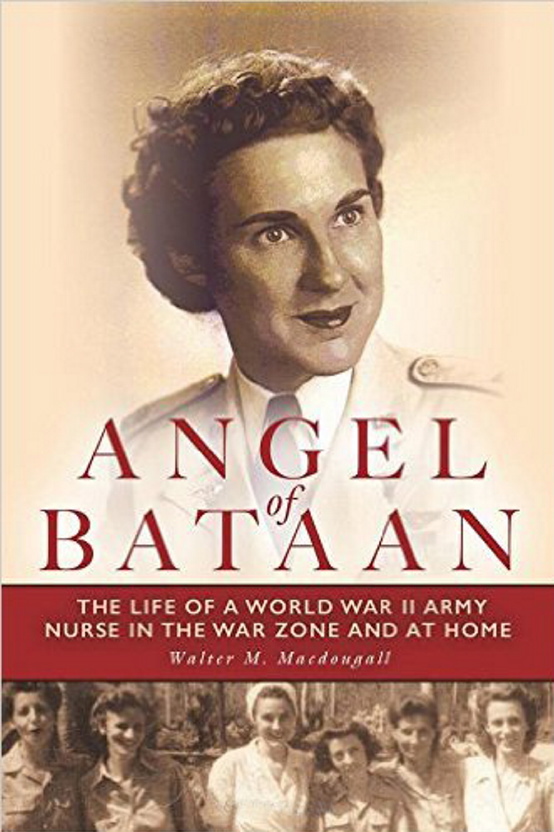

There was a time when practically everyone knew the name of Lt. Alice Zwicker of Brownville, Maine. She was one of the 77 Army nurses known as the Angels of Bataan, who were imprisoned by the Japanese after the fall of Manila, Bataan and Corregidor at the outset of World War II.

Upon her return home, Alice, though in poor physical condition, became a spokeswoman for the Army, re-enlisted in flight school, became a captain and even found herself pictured on sheet music with Gen. Douglas MacArthur. She was the only Maine woman to be a prisoner of war during either world war.

Walter M. Macdougall’s biography of Zwicker follows her life from birth in Maine in 1916 to her death in Brooklyn, New York, in 1976. It is a calm, thoughtful work that moves the reader from start to finish, while informing about life, times and inner self. Readers who enjoyed Macdougall’s “The Old Somerset Railroad: A Lifeline for Northern Mainers” (2000) will find the same qualities in “Angel of Bataan.”

A resident of Milo, Macdougall lays the foundation for Zwicker’s story with her family and the village of Brownville in the 1920s and ’30s, observing, “Quiet people with strong moral principles give a small town its solidity; characters who may have good values underneath, but are somewhat questionable on the surface, give a village its color.”

Zwicker’s parents moved to Maine from Nova Scotia, where they started a family of seven children. They were hard-working, close-knit and church-going, and they encouraged the children to get an education rather than take up mill work. Though Piscataquis County provided a good place to raise their family, their German name attracted slurs of “Hun” and “Nazis” from some quarters.

The reader learns much about education by following Alice through nursing school at Bangor’s Eastern Maine General Hospital, where she graduated in 1937 after interning in Boston hospitals. By 1940, she was head surgical nurse at Eastern Maine General, but dreams of travel, the Army and “the plum of romantic assignments in the subtropical paradise of Manila in the Philippines” drew her.

On Oct. 12, 1941, Zwicker arrived at Fort William McKinley, just south of Manila, and the defining adventure of her life began. Evacuation of nonessentials was already underway but the beaches and the nightlife lived up to the Army brochures. Zwicker sampled the last bit of American colonialism and took to her medical duties seriously.

This is a picture handled well by Macdougall, and so is the Japanese air attack, followed by land invasion and the retreat from Manila to the Bataan Peninsula to the island fortress of Corregidor, as seen through the eyes of Alice as a nurse. The women were given noncombatant papers, and their chief nurse did everything to keep them together as a group. Rather than being marched off to death camps, they were placed in Santo Tomas camp for civil internees.

The chapter on prison and liberation are well worth reading, because they contradict what many of us heard and thought we knew just after the war. The Japanese guarded the camp, but “had no intention of feeding the captives.” What had been the American Emergency Committee provided loans of money, and the internees were largely free to run the camp. They were required to work, and the nurses kept together as an Army medical unit. In 1945, all came to a harrowing but successful conclusion.

It was Zwicker’s return to civilian life that was, perhaps, most difficult. She was not bitter, and even as the war raged and she re-upped and urged others to do so, she denied rumors of rape and torture at her prison camp, a truth confirmed by fellow nurses. She married a fellow prisoner of war who quickly divorced Zwicker when they discovered she had tuberculosis.

After a long struggle back to health, she found new faith, overcame depression, continued her formal education, married happily and went on to live year-round in a cottage at Bonny Eagle Lake in Standish. Through her colorful life she contributed, endured and found value like few of us can match.

William David Barry of Portland is a historian who has authored/co-authored seven books, including “Maine: The Wilder Side of New England” and “Deering: A Social and Architectural History.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.