ROCKLAND — Andrew Wyeth called him Maine’s best photographer. Life magazine published his photos. But until this year, the photography of Kosti Ruohomaa has been largely underappreciated in his home state.

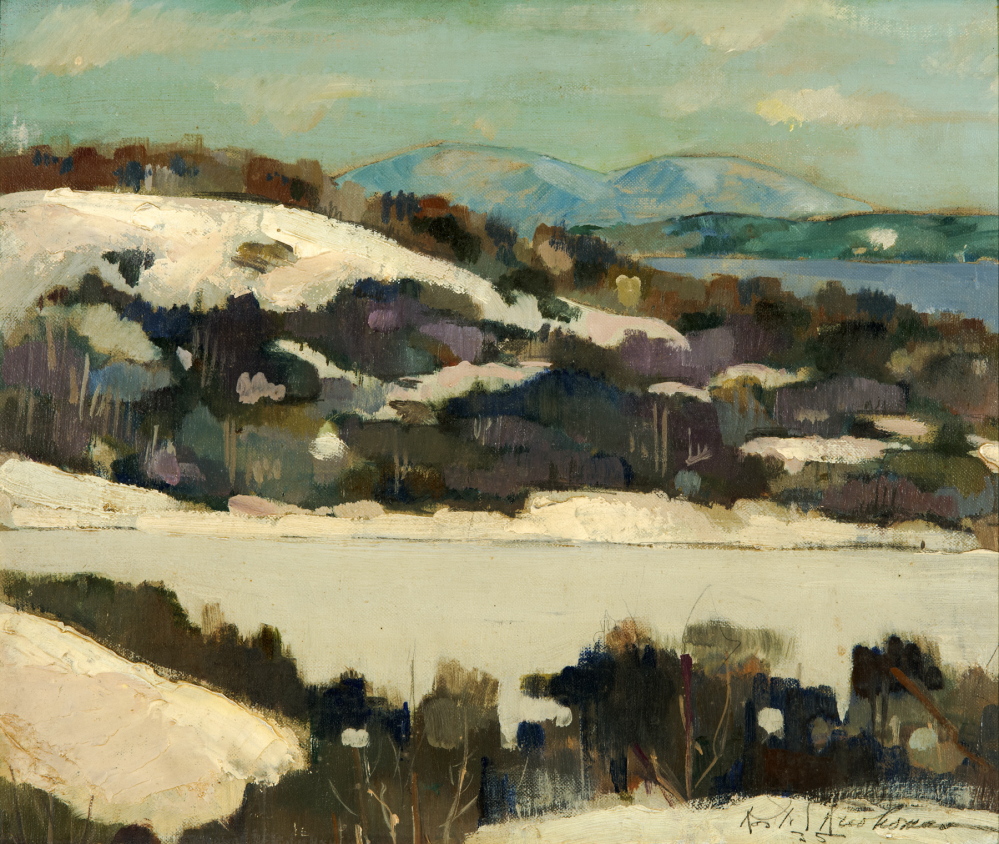

As part of the ongoing Maine Photo Project, the Maine State Museum in Augusta is showing his work in a newly opened yearlong exhibition, and the Farnsworth Art Museum in Rockland pairs his photos with paintings by Wyeth, who was a close friend. Wyeth, a famously private painter, felt so comfortable with Ruohamaa (row-home-a) that he invited him along on painting excursions. The result of one of their collaborations showed up in Life in 1953, under the headline “Artist Paints a Ghostly House.” Ruohomaa photographed Wyeth as he painted an abandoned Waldoboro farmhouse, and the magazine reproduced some of Wyeth’s paintings from the afternoon.

After Ruohomaa’s death in 1961 at age 47, he began to fade from the state’s collective memory. The Maine Photo Project puts him back in front of us.

Maine State Museum curator Deanna Bonner-Ganter knew of Ruohomaa through a past association with Maine Media Workshops in Rockport. Bonner-Ganter found it shocking that few others knew much about him.

“He’s a legendary photographer of Maine,” she said, “and that’s saying something, because we have wonderful photographers in Maine.”

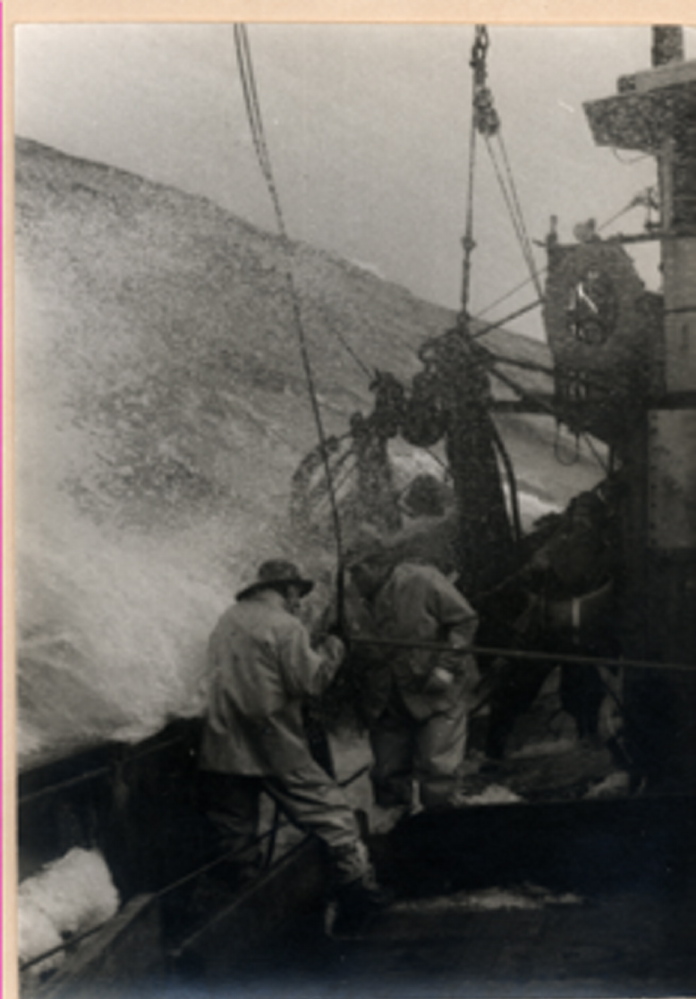

Ruohomaa photographs are distinguished by a ruggedness and independence that was associated with life in Maine in the 1940s and ’50s, when Ruohomaa did most of his work for magazine readers. He went into the woods with lumberjacks and on boats with fishermen. He went to Monhegan – in the winter. He photographed the town meeting in Washington in 1948, putting the tiny community before a national audience. He convinced his editors to let him do a photo essay that captured the mood of Maine in the winter and enlisted Brunswick poet Robert Tristram Coffin to write poems to accompany the pictures. For another story, he documented the son of Finnish immigrants.

Ruohomaa was born in Quincy, Massachusetts, in 1913 and moved to Maine in 1924. His parents bought 240 acres on Dodge Mountain in Rockland, where they enjoyed magnificent views of Penobscot Bay and blueberries. The family harvested blueberries, and wherever his work took him, Ruohomaa returned to Maine each August to help with the harvest.

He was a photojournalist who approached his work as an artist, Farnsworth curator Angela Waldron said. That partly explains the mutual respect between Wyeth and Ruohomaa, she added.

“They were both fascinated with the connection between people and their environment, and they both found in Maine a constant source of inspiration for their work,” Waldron said.

The two men met when Ruohomaa showed up unannounced and uninvited at Wyeth’s home one afternoon in 1950, two years after Wyeth painted “Christina’s World.”

“Andy opened the door, and there was Kosti,” Waldron said.

Instead of turning him away, Wyeth welcomed him. He knew the photographer’s work through Life, and was eager to get to know the man. They became friends and worked together often over the next decade. Wyeth appreciated Ruohomaa’s passion, which Wyeth attributed to his Finnish heritage. “Northern people, like the Finns, withdrawn though they may appear, are capable of extreme passion,” Wyeth wrote in the introduction to a 1977 book about the photographer. “Kosti Ruohomaa had the insight and intelligence to see through his lens the essential character of Maine and its people.”

The two exhibitions in Maine feature a range of his work. At the Farnsworth, Waldron paired Ruohomaa’s photos with paintings by Wyeth that share common themes: fishing, lumbering, the blueberry harvest and life at home.

At the Maine State Museum in Augusta, the Ruohomaa exhibition traces his evolution as an artist, beginning with his education in Rockland schools and continuing through his time in Boston at the School of Practical Art. His first job was as an advertising illustrator near Boston.

He bought his first camera in 1937, and in 1938 went to work for Disney Studios in California. The hiring was big news in Rockland, where the local newspaper reported the “distinct honor,” noting he was among hundreds who applied for the position.

He traveled cross-country by train, and it was during that trip he became familiar with his camera. He took photos along the way, shooting from the platform on the back of the train. In California, he learned to use the camera for greater good. Disney encouraged its artists to visualize light, mood and movement, Bonner-Gantner said.

He was a quick learner. Ruohomaa won a national photography contest in 1939, and soon his photos were published and distributed nationally. He returned east in 1943.

His career benefited from the ascent of picture magazines, Bonner-Gantner said. Photographic processes and new printing techniques changed the publishing business, and magazines like Look, National Geographic and others flourished. Ruohomaa was in the right place at the right time, and he had the right background to become a leading photojournalist, she said. He worked across North America and overseas, but he was known for his photographs in Maine and New England, Bonner-Gantner said.

“His motivation was always to capture what he perceived as a vanishing way of life,” Bonner-Gantner said. “He wanted to capture the people close to the land and close to the sea. He respected them, and Maine was a rich source for his work.”

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.