A couple of years ago, a fellow film critic and I tried to answer a question: What was the definitive film of the 1990s?

There were different strains of zeitgeist floating around in the ’90s, and different films captured them. High on our list were Quentin Tarantino’s “Pulp Fiction” and Oliver Stone’s “Natural Born Killers,” two films from 1994 that epitomized the decade’s fascination with amoral violence. Also in the running were two indie comedies about youthful ennui, Richard Linklater’s “Slacker” (1991) and Kevin Smith’s “Clerks” (1994). Ultimately, we decided the winner was David Fincher’s “Fight Club” (1999), because it distilled an entire generation’s nagging sense of dissatisfaction into one angry, stylish, nihilistic comedy.

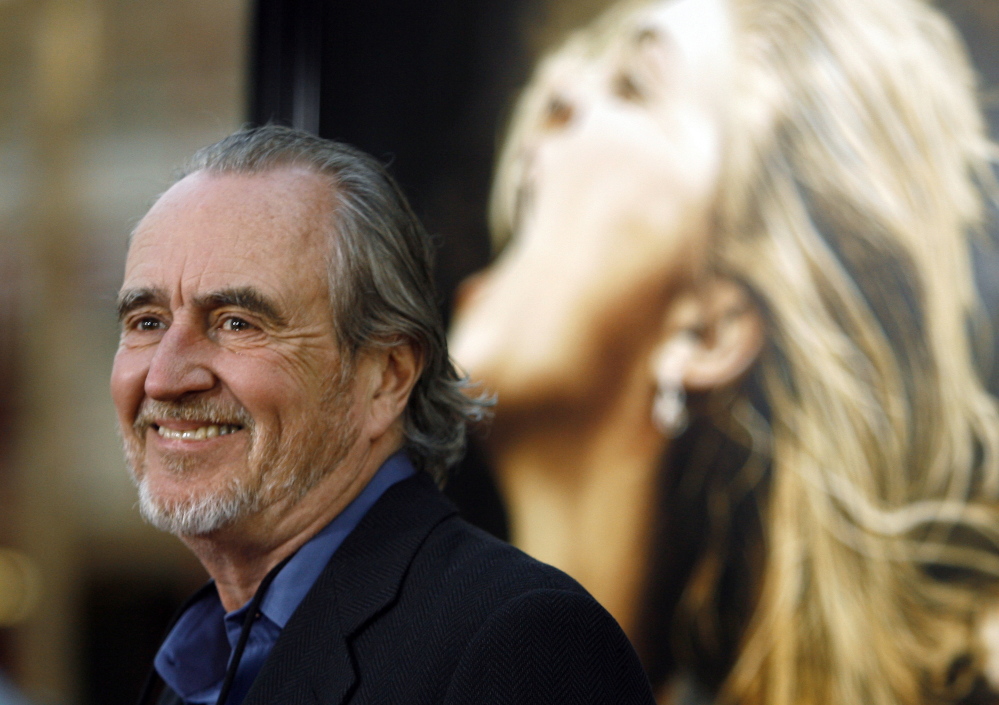

With the death of Wes Craven last week, though, I realized that we missed a major contender: his 1996 horror movie, “Scream.”

And not just for its only-in-the-’90s cast of Neve Campbell, David Arquette, Courtney Cox, Skeet Ulrich and Rose McGowan. “Scream,” a horror movie about horror movies, was the ultimate meta-movie for a meta-obsessed decade. Like David Foster Wallace’s self-annotated novel “Infinite Jest” – published the same year – Craven’s “Scream” came with built-in commentary. If the ’90s generation was defined by its suspicion of mainstream culture and its inability to find a way out of it – think Kurt Cobain – then “Scream” is surely one of the decade’s definitive movies. It neatly captured the feeling that modern life was a series of cultural Russian dolls, and any attempt to critique it only created another, larger doll on the outside.

Not that Craven or screenwriter Kevin Williamson would have necessarily put it that way. “Scream” was, at bottom, a slasher movie. It was part of a genre that had been over-mined and utterly exhausted throughout the 1980s thanks to the franchises “Friday the 13th” and “Halloween.” Each installment in those series became increasingly dull-witted and derivative, until the movies began to feel like parodies of themselves.

Of course, that’s exactly what “Scream” was. Its central figure, Ghostface, was a comically familiar horror-movie trope. A serial killer with a tortured emotional backstory, Ghostface wore a creepy mask (an open-mouthed face clearly modeled on Munch’s 19th century painting “The Scream”) and he used his almost preternatural cunning to prey on attractive young people. From the get-go, the movie’s premise was beyond cliche.

But “Scream” knew it. What’s more, its characters knew it. The attractive young people in “Scream” were so familiar with horror movies that they discussed them constantly. They almost seemed to know they were in one. This was unusual. Until “Scream,” there was an unspoken rule that characters in horror movies did not watch horror movies. That made for a fairly unrealistic portrait of your average babysitter or high-schooler, but filmmakers generally didn’t want to break the fourth wall and jolt audiences out of the movie experience. Nevertheless, one of the very first lines in “Scream,” uttered by Ghostface to pretty young Casey (Drew Barrymore), is this: “What’s your favorite scary movie?”

What follows is an over-the-phone discussion of “Halloween” versus “A Nightmare on Elm Street” – a wry nod to Craven, who directed that one. (Casey says she liked the original, “but the rest sucked.”) These references, though, aren’t what makes “Scream” so unique. The movie goes even further, with a now-famous speech by Randy, a film geek played by Jamie Kennedy, which outlines the basic rules of slasher movies. Here’s his speech:

“There are certain rules that one must abide by in order to successfully survive a horror movie. For instance, number one: You can never have sex. Big no-no! Sex equals death. Number two: Never drink or do drugs. The sin factor! It’s an extension of number one. And number three: Never, ever, ever, under any circumstances, say, ‘I’ll be right back.’ ‘Cause you won’t be back.”

At the time, the average moviegoer was at least subconsciously aware that movies followed formulas, but the idea that movies followed actual rules, and ones that enforced ethical codes and moral values, wasn’t terribly widespread outside of film studies classes (or movie studios). “Scream” treated the horror genre as what the academics would call a text, something to be analyzed, criticized and, according to the fashionable literary theories of the time, decoded for hidden meanings. Roger Ebert put it this way in his review: “‘Scream’ is self-deconstructing; it’s like one of those cans that heats its own soup.”

Though Williamson’s self-reflexive script is what gave “Scream” its zeitgeisty vibe, Craven was the perfect director for the job. He was something of an academic himself, having majored in English and psychology at Wheaton College and then earning a master’s in philosophy and writing at Johns Hopkins University. He briefly served as an English professor and a humanities professor before going into movies (porn, at first, under pseudonyms). His breakout film, “Last House on the Left” (1972), was a brutal rape-revenge film inspired by an unusually highbrow source: Ingmar Bergman’s “The Virgin Spring” (1960), itself based on a medieval Swedish ballad.

Craven never got overtly artsy, though. “Scream” opened with a genuinely terrifying scene (it’s an indirect nod to “Psycho”) and was initially so gruesome that the MPAA slapped it with an NC-17 rating. A series of cuts, and the personal intervention of Dimension Films executive Bob Weinstein, convinced the MPAA to grant an R rating.

“Scream” went on to become a $173 million success and inevitably launched a franchise of three more films. It was also blamed for a handful of supposed copycat crimes, one of which involved two teens who planned to purchase Ghostface costumes and go on a murder spree. The fact that “Scream” spawned a Halloween costume says something about the movie’s popularity.

By the fourth film, the characters in “Scream” were discussing the rules of sequels, and the franchise had become centered around a fictional franchise-within-the-franchise called “Stab.” The critic Dana Stevens once compared Craven’s entire labyrinthine series to a Borges story.

Today, when people think of meta-movies, they tend to think of the screenwriter Charlie Kaufman (“Being John Malkovich,” “Adaptation,” “Synecdoche, New York”). Then again, meta-maneuvers in movies are so common that people barely notice anymore: The recent comedies “22 Jump Street” and the new “Vacation” both cracked jokes about their sequel-ness, but nobody went around comparing them to Borges. The whole concept of “meta” may just be another outdated fashion of the 1990s – like, say, irony.

At any rate, “Scream” got there first. It was the right movie at the right time. It was self-aware, and aware of being aware. And in the end, it became part of the very thing it critiqued.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.