The headline show at Caldbeck Gallery features paintings by Bayard Hollins. They are bright, lively and squishy. It’s a whole lot of bold. But, in fact, it’s too much.

I can handle busy: I like Pollock and de Kooning, for example, and my favorite stops at the Louvre include the giant Salon machines such Théodore Géricault’s 1819 “Raft of the Medusa” and Eugène Delacroix’s 1827 “Death of Sardanapalus.”

But complexity needs both a system and a reason. With Pollock and de Kooning, the works are far too complex to be able to memorize, so the viewer is compelled to linger for a non-portable experience that happens in real time. You don’t remember the pieces per se – but your experience of them.

Hollins’ work is not similarly ambitious. Brightly colored and highly energized landscapes do not purport such a conceptual edge (a point underscored by the small but conceptually hefty landscapes hung in numbers in Caldbeck’s second floor galleries). Hollins seems to be leaning on the standard stuff of painting: composition, color, light, rhythm, descriptive efficiency and brushy bravado. But he’s caught between worlds like he’s trying to paint a Maine landscape with an abstract vocabulary. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, but Hollins’ anything-goes approach loses touch with coherence, which he then tries to reel in with passages of legibility that are overly simplified. For some viewers, the zigzagging lines of trees might feel familiar enough to ground the work, but for me it pushes into an uncomfortable simplicity. The bright colors come to feel unmediated and right-out-of-the-tube (even if they aren’t).

The obvious comparison when it comes to the heavily stylized approach is Eric Hopkins, whose works can be seen right around the corner at Dowling Walsh. But Hopkins traffics in efficiency: He wants his paintings to be quick and fun – not complex and profound. What Hopkins is doing is much closer to wit – while it’s a lightning bit of design, it’s supposed to feel effortless and entertaining.

Hollins’ “View from Horsehead Island” is a 6-foot landscape canvas. The sky is jumping like a van Gogh, except that van Gogh’s skies are coherent. Picture, for example, the Museum of Modern Art’s 1889 “Starry Night.” Van Gogh’s night sky has a system. It swirls around the stars from the cypress on the left, uphill over the town toward the beckoning moon in the upper right. Hollins’ summer sky might be building thunderboomers in a late June afternoon, but it’s hard to tell because the pink, blue, yellow and white squishy strokes seem to be exploding all over the place. And the insistent rhythms of the trees across the water don’t quite mesh with the branches of the trees in the foreground. We want to fold all these staccato marks into the same surface, but they are so dissonant that the rhythms fight each other instead condensing into coherence.

Hollins’ 3-foot square “The Weight of a Storm” comes closer to succeeding and seems to better reveal the artist’s project. We are grounded by a band featuring three low islands and the sliver of a sunset sky behind them – all in the bottom tenth of the square. The angry sky, given context by the Lilliputian islands, powerfully dominates the scene. The clouds zip and dart and clank about. The sky leaks pink and yellow from its purple, gray and blue passages. The squishy strokes start to build enough clout to convince us the yellow is ripening lightning just about to strike… but the zigzag strokes of the overly stylized trees (again, think Hopkins) empty the potential flash of its strike.

Most frustrating to me was a long, horizontal scene with a complexly cloudy sunset sky that is just calm enough to be exciting and beautiful. But the overly simplified tree zigzag of an island punctuating the painting in the bottom right scratched out the dreaminess of the scene. Without that predictably recipe-like passage, we could bask in the pulsing, brushy riffs of the scene – and Hollins is enough of a painter to make me long for that.

UPSTAIRS AT CALDBECK is a three person show featuring the work of Dozier Bell, Alan Bray and Kristin Malin that could hardly be more impressive.

Malin’s work includes about 20 5-by-7-inch aluminum panels painted with a repeated view from her Georgetown studio. The repetition is only of the subject, reminding us that the best paintings each succeed on internal logic. And Malin’s little paintings all work: Each bristles with the focused intelligence of an individual moment of clarity.

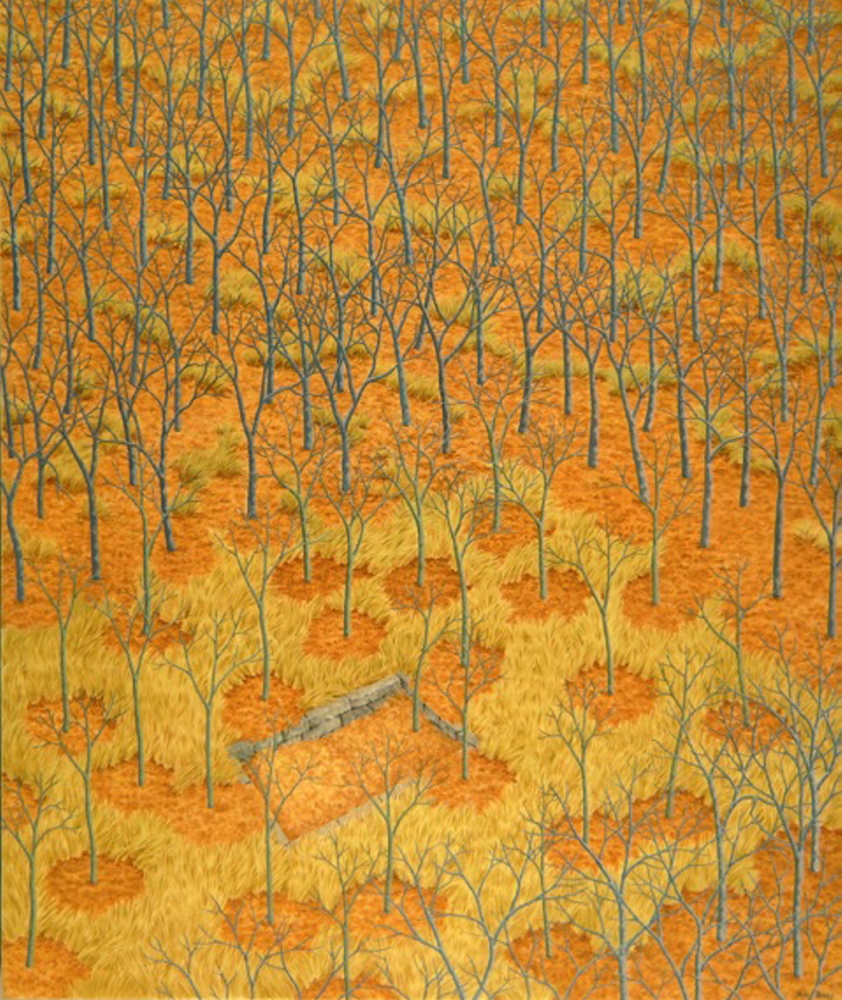

Bray is one of Maine’s most interesting painters. His works deserve a much longer look, but their quirkiness arrives in a hallucinatory flash that illuminates like night lightning (which allows us to scan our memory image even after the light is gone). Bray paints elements of cartoon legibility, but with a renaissance master’s dedication to detail (as if Giotto came to paint on the coast of Maine). “Ghosts,” for example, features a forest of rather identical deciduous trees just after they have dropped their leaves in matching, ochre piles that stem yellow grass that has appeared in what we come to see as a rectangular house lot, otherwise only marked by the stony foundation that still drops two feet into the erstwhile basement. The way his uncanny narratives lean away from the rational, Bray is like the Edward Gorey of Maine landscape painting: His works are both delirious and delicious.

Bray’s and Malin’s quirk and clarity are joined by Dozier Bell, whose tiny charcoal on Mylar landscapes can only be described as sublime. Whatever power you believe in can find its way to you through Bell’s images – however spiritual or secular you may be. We’ve all seen Bell’s night-dark landscapes in our dreams: a bog in a forest where the water’s reflection limits us at the edge of where we cannot pass, five crows silhouetted straight up in nocturnal clouds, or sunrise’s first glimpse through the weather-gnarled pines atop an inaccessible ridge still dark with night.

The works in Caldbeck’s three-person show remind us that landscape generally needs a sense of intimacy to draw us in. Even the Hudson River School relied largely on the psychological rather than physical scale of painting. And the sublime, as Bell reminds us, is a system – one that is beyond our comprehension, to be sure, but something we must be able to sense as a significant entity, even if it is beyond fathomable form.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.