After a bill that would have made it harder for parents to skip immunizations for schoolchildren failed in the Maine Legislature this spring, schools across the state are on the front lines dealing with vaccinations and will potentially be most affected by any disease outbreaks. The fall is when schools send notices to parents asking them to be up to date on their vaccines.

But Maine’s weak immunization laws make it impossible to do much, school and public health officials say, because parents have the legal right to opt out. That makes it a steep climb to try to improve school vaccination rates, which are among the worst in the country despite some improvement in 2014-15 compared with 2013-14.

Maine’s low vaccination rates put the state’s children at risk for outbreaks of preventable diseases such as measles, chickenpox and pertussis.

“We go as far as we are allowed to under the state law to encourage immunization,” said Ken Kunin, South Portland’s superintendent of schools. The district’s Small Elementary School had one of the highest first-grade opt-out rates in the state for the 2014-15 school year, with 20 percent of parents forgoing vaccines for their children. Small school also had one of the worst opt-out rates for the measles vaccine.

For the first time this spring, the Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention released school-by-school vaccination rates, giving parents the opportunity to see their school’s data.

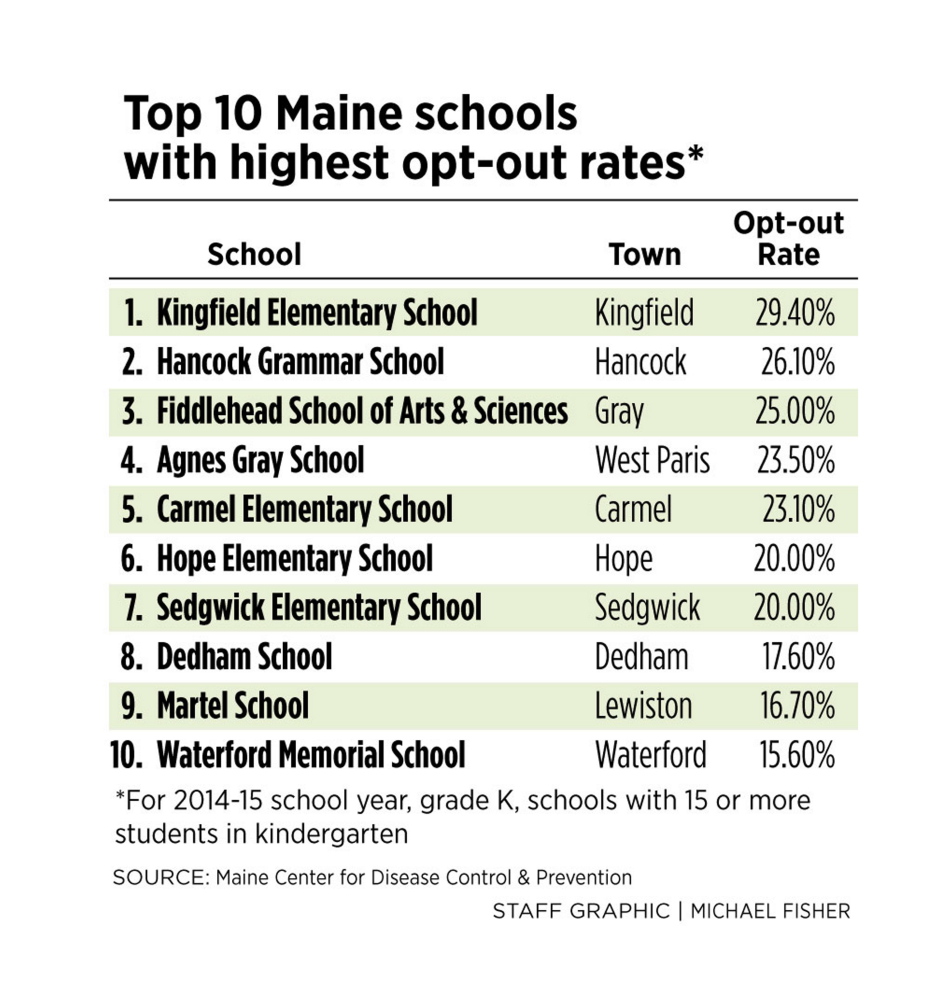

While Maine’s overall voluntary opt-out rate was 3.9 percent, there are pockets of vaccine resistance, with more than 60 schools having opt-out rates of 10 percent or higher for kindergarten or first grade. Some parents are fearful that vaccines cause autism or are unsafe, despite hundreds of studies proving vaccines are overwhelmingly safe and that there’s no link to autism, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Maine’s opt-out rate for 2014-15 was eighth-highest in the United States, and more than double the national average of 1.7 percent.

Kunin, who took the helm Aug. 1 as superintendent, said nurses will be having one-on-one conversations with parents and encouraging them to talk to their primary care doctors about vaccines.

But Kunin said South Portland’s approach to vaccinations won’t be much different from years past, because he says the law does not allow the district to be more aggressive.

“We have to abide by the law, but I’m 100 percent in favor of changing the law,” Kunin said.

A bill would have required a signature by a doctor or medical professional before parents could opt out of vaccinations for their children.

The current law allows parents to simply sign a form when opting out of vaccinations on philosophic or religious grounds. Maine is one of 18 states that permit parents to opt out on philosophic grounds. Some states are tightening their vaccine requirements, and California, after a Disneyland measles outbreak this year sickened hundreds, eliminated the philosophic exemption. Other states have passed laws requiring a physician’s signature to opt out, like Maine lawmakers tried to do.

Meanwhile, schools that want to try to improve vaccination rates don’t have many tools to do so, said Dr. Laura Blaisdell, a Yarmouth pediatrician and vaccine advocate.

“The schools’ hands are tied,” Blaisdell said. “Parents have legal rights. I can understand why school administrators would not want to touch this.”

The Maine Association of School Nurses supported the doctor’s signature bill, sponsored by Rep. Linda Sanborn, D-Gorham, who is a doctor. The Legislature overwhelmingly approved the measure, but Gov. Paul LePage vetoed the bill in June and the House fell a few votes short of overriding the veto. LePage’s veto message supported vaccines, but said the bill infringed on parent choice.

Pro-vaccine legislators say the unvaccinated endanger others, including immune-compromised children who can’t get vaccines, and infants too young to have all their vaccines.

Teresa Merrill, president of the Maine Association of School Nurses, a trade group, said school nurses traditionally send out the paperwork and obtain signed exemptions for everyone who doesn’t vaccinate. Anything beyond that would be asking the nurses to step into a role that should be reserved for pediatricians or others, she said.

“The law is very specific and obviously we have to follow the law,” said Merrill, who is also the school nurse at Great Falls Elementary in Gorham. “We don’t get involved in counseling a parent directly about vaccines. That’s up to their primary care physician.”

Janet Anderson, principal at Camden-Rockport Elementary School, which had one of the highest opt-out rates for kindergarten and first grade in 2014-15, said many parents have strong feelings about vaccines. The school’s role is to hand out the form and explain the consequences if there’s an outbreak. Unvaccinated children can be required to be kept home for 21 days during a preventable disease outbreak.

“We’re caught in the middle,” Anderson said. “We must respect parents’ personal decisions.”

Sanborn, the Gorham legislator, said she wishes that schools would do more public health education. But she said the most effective way to improve vaccination rates would be to change the law.

Sanborn said she’s not giving up on the bill, vowing that she or another lawmaker would bring it or a similar bill back in upcoming years.

“We are very committed to making this happen,” she said.

Copy the Story Link

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.