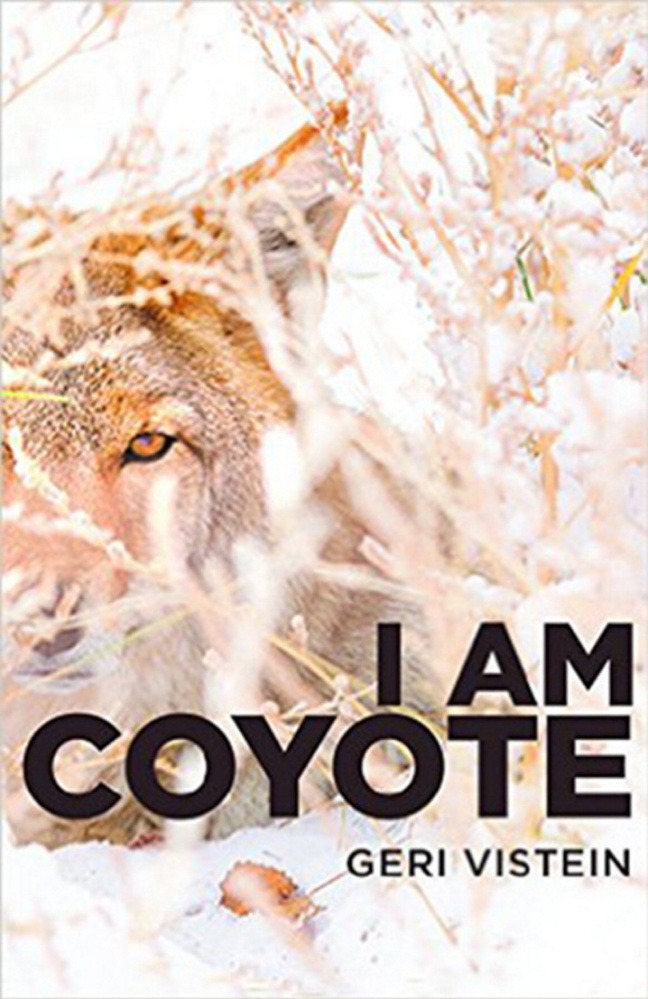

“How are we ever to understand and appreciate the intelligent carnivores who live among us so warily and elusively, rarely allowing us even to see them?” asks Geri Vistein at the beginning of her ambitious but flawed book, “I Am Coyote.” It’s a question worth asking about most members of the animal kingdom, whether they are wary and elusive or not. But Vistein is a carnivore conservation biologist, and she could hardly find a better companion in her quest for an answer than that survivor par excellence, the coyote.

Written in the third person (despite the title), her book tells the story of a young female coyote who wanders out of Algonquin Provincial Park in Ontario, where she was born, and having survived a dangerous migration, ends up in Baxter State Park. Here she meets a mate, and together they establish a multi-generational family as coyotes and other canines have done, Vistein reminds us, for hundreds of thousands of years. From Coyote’s growing family in the park, the species will go on to fill the ancient place of top predator, once occupied by the wolf, throughout Maine and New England.

Coyote’s encounters are seen from the animal’s perspective throughout. Although Baxter protects her from human threats, there are plenty of other dangers to keep the story moving. The author knows her stuff, and without going into spoiler details, the action is credibly described in terms of objective coyote behavior.

Although this is a fictional story, actual months and years benchmark it from beginning to end. Thus, according to “I Am Coyote,” when the animals couple for the first time – beautifully described (Vistein must have watched mating coyotes in her field work) – in the deep winter of 1970-71, it is the “first coyote life to be created in Maine.” She goes on with felicitous understatement: “It was a historic moment for their kind, but the world knew nothing of it, and it was better so.”

Historically, there were never coyotes in Maine. However, records of coyotes reaching the state go back to the 1960s, and it is likely that the first Maine-born pup was conceived a good deal closer to the Canadian border than Baxter Park, slap in the middle of the state. So all this represents a certain poetic license.

Besides the physical, Vistein writes, “there is also the inner journey in the life of an intelligent, sentient being – and the inner journey is the heart of this narrative.” This, I am afraid, is where the author comes unstuck. I don’t doubt that the glowing descriptions of coyote interactions are based on the author’s observations as a lifelong field biologist. No doubt many of them are easily described in terms of cunning, family bonding and “ancient wisdom.” But the freedom with which she imputes human intention and emotion to her subjects severely undercuts the publisher’s claim that this book is adhering to “the highest standards of wildlife biology.”

“Her parents were utterly supportive of each other,” recalls a dreaming Coyote. When a young male meets his future mate, “There was such honesty in their encounter, and from that honesty came trust.”

Sentiments like these would be fine in an animal story for children, but it is absurd to apply them to even the most sentient of wild animals in a work purporting to be scientific. When Coyote and her mate howl for the first time in Baxter Park: “All life felt it, and the mountains remembered it.” Lyrical, yes, but even if coyotes could remember, mountains certainly can’t. It all begs the question, for what audience of readers is this book intended?

In the end, “I Am Coyote” tries to be too many things. As a fictional animal story, it has perfectly wonderful passages that bring the woods and waters to life. Then without warning, we are suddenly being addressed as if by a teacher: a delightful description of the newborn pups’ first view of the world outside their den ends with a clunk as the reader is informed that a “complex, imperative, instructional endeavor” has just begun. Or a lively picture of coyotes pouncing on small rodents – their staple diet – is interrupted with the information that “Coyotes are an apt predator to manage rodent populations and the diseases they can cause.” With this didactic tone, the narrative begins to seem as if it were guided by a checklist of ecological data.

“I Am Coyote” has some lovely moments in it. Coyote’s death, of old age, is truly affecting. But elsewhere the mix of anthropomorphism and ecological observation render neither them nor the book itself convincing.

Thomas Urquhart is a former director of Maine Audubon and the author of For the Beauty of the Earth.

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.