WASHINGTON — The saddest part of the mostly heartwarming story of singer Eva Cassidy is that she had to die to get the renown she deserved.

Cassidy, an eclectic cover artist who grew up in Bowie, Maryland, has amassed sales of more than 12 million albums. Musicians who played with her and a small, devout passel of fans still talk about her concerts with you-had-to-be-there reverence.

“We’re still applauding Eva Cassidy,” says Mick Fleetwood, the Fleetwood Mac co-founder and drummer, who became a devotee of Cassidy’s while listening to her sing at Fleetwood’s, the Alexandria, Virginia, restaurant he owned and operated in the mid-1990s. “We’re keeping the campfire burning, letting people know about her. We want people to know about her!”

Yet, for all the devotion of those left behind, it remains true that you can take away every album sold before Cassidy died of cancer at age 33 in 1996, and that wouldn’t make a dent in her overall numbers. And that there was precious little demand for her as a live performer during her career.

Throughout the year before she died, Cassidy and her tight and tight-knit band played regularly at Shootz, a billiard room in Bethesda, Maryland. The cover charge for her Shootz shows was $3, which bought you four sets by Cassidy and her band – a cohesive ensemble willing and able to play jazz or blues or torch songs or whatever Cassidy felt like playing that night – plus $3 in pool credit.

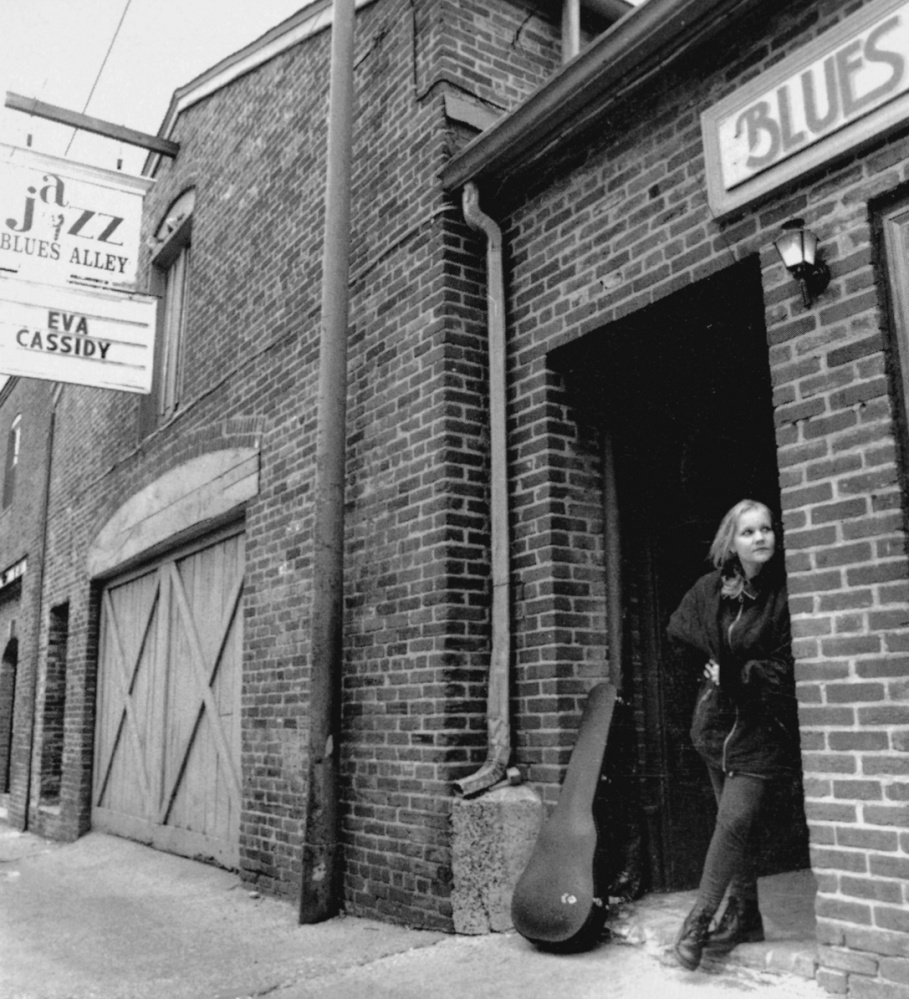

These days, Fleetwood (who occasionally sat in with Cassidy and her band) is one of literally millions of music fans around the world who are assured that Cassidy’s voice should never have had to fight racked billiard balls for attention. Next month marks the 20th anniversary of her first headlining gigs at Blues Alley, a pair of performances that were supposed to improve her professional lot, and which are largely responsible for the posthumous fame.

“It all goes back to Blues Alley,” says Chris Biondo, her bassist, producer, sidekick, ex-paramour, and, to this day, most devout supporter.

The shows were recorded and proved at long last that she was indeed fit for the finest music rooms. The anniversary of the gigs is being commemorated with the release of “Nightbird,” a 33-song set taken almost entirely from one of her nights at the hallowed Georgetown club.

“We always had trouble getting Eva to finish things, like a (studio) record,” Cassidy’s arranger and pianist Lenny Williams says. “Al (Dale, Cassidy’s longtime manager) wanted a recording, and Chris thought doing a live album, getting it out quickly, getting her something she could sell, something for critics to write up, was the answer. And Eva said yes.”

They aimed high when targeting a venue for the project: Blues Alley, a nightclub that despite its small size – capacity is only 124 – has since 1965 hosted jazz titans including Sarah Vaughan, Maynard Ferguson, Ella Fitzgerald, Dizzy Gillespie, Wynton Marsalis and on and on.

Cassidy had occupied the Blues Alley stage before, but as part of a duo with D.C. music legend Chuck Brown, and everybody in her circle knew that it was the go-go godfather, and not Cassidy, that brought such a booking.

But Dale talked management into letting her headline a show with her band. He got two nights, in fact: Jan. 2 and 3, 1996.

“The club gave us the two worst nights for clubs in America,” says Williams, laughing. “Right after New Year’s, when everybody’s worn out from the holidays. Nobody goes out.”

But bad dates sometimes beat the heck out of no dates. Cassidy took the offer.

Since all expenses were coming out of pocket, the Blues Alley recording was done on the cheap. Biondo says he helped the recording engineer load in all the equipment to get a break on the regular rate. He also used a box of pre-owned digital tapes he bought at a deep discount.

As things turned out, it was a good thing they had an extended stay.

Shortly after the band left the club to huge huzzahs from the packed house after the opening show, Biondo and Williams sat down to check out the tapes. And they got crushing news: “There was a hum from beginning to end,” Biondo says. “It wasn’t something we could work around. It was a deal breaker.”

Nothing was salvageable. Biondo decided to record over everything from the first night. That left one show to nail every note. Or at least try.

“So what you got the second night was a very pissed-off band,” says Cassidy’s longtime drummer, Raice McLeod. “We all knew the first night was terrific, and we were relaxed and comfortable probably because we knew we had another night coming. But that’s all lost. Now we’ve got a one-shot deal.”

Guitarist Keith Grimes says he fretted that Cassidy’s worrying about the opening night’s sonic disaster would hinder her performance for the closing show. No need.

“Mostly I was savoring the experience of playing for an audience that appreciated us, and I knew a Blues Alley audience would,” Grimes says.

“I didn’t want Eva to fixate on wasting the first night, and just told her, ‘Everything’s going to be beautiful, they’re going to love it, let’s go do it!’ And we did.”

For all the worries, Biondo says, the tapes from the second show played back as wonderfully as he had hoped.

CASSIDY, BIONDO and Dale formed their own label to release the recordings and called it CBD Records after the initials of their surnames. To pay for the manufacture of CDs, Cassidy used money she had been given by an aunt. Biondo recalls Cassidy being pretty sure she had wasted the gift.

“We’d ordered a lot of a thousand CDs,” says Biondo. “I remember driving with her to Virginia to go pick them up from the CD plant. She thought we bought too many. So the whole ride she was saying she knows she’ll have boxes and boxes of them lying around forever, really concerned that for the rest of her life she’d be seeing these things in her basement. I was telling her don’t worry about that, that it would be fine. But, I thought it would be a great thing to sell the 1,000 we had.”

Biondo probably would have been content if the Blues Alley recordings improved Cassidy’s local fame enough to get her out of Shootz forever.

As things turned out, the recordings brought her international acclaim, and millions of “Live at Blues Alley” discs have been sold.

But those sales didn’t come on CBD Records. “Live at Blues Alley” was originally released in May 1996. Weeks later, while Dale and members of the band were still hand-delivering copies of the disc to area record stores in hopes they would offer it for sale, Cassidy showed up limping to a record-release party; doctors told Cassidy her hip had been destroyed by cancer, which until then she was unaware she had. She soon learned the disease had spread throughout her body, and that she didn’t have long to live.

About a month before Cassidy’s death, her friend and fellow local musician Grace Griffith sent a CD of Cassidy’s recordings to Blix Street Records, a folk label based in Gig Harbor, Washington. Griffith told Blix Street boss Bill Straw that Cassidy deserved a record deal, and that she was terminally ill.

THAT CASSIDY DIDN’T HAVE a record label was part bad luck and part her own choice. The iconic jazz label Blue Note infamously passed on signing her, but others came calling. Fleetwood remembers Cassidy telling him about a trip to the offices of a New York label that went south when a record executive began telling her what she should sing.

“I said, ‘You may have to be open to some of these suggestions that some of these people might have!’ ” recalled Fleetwood, who now lives in Hawaii, by phone. “And Eva said, ‘Mick, I’m not that person.’… She was very adamant about not compromising.”

After hearing the CD that Griffith gave him, Straw says the record label boss part of him wanted to get on a plane and fly to D.C. and sign Cassidy before anybody else did, prognosis be damned. But the humanitarian in him kept him from disturbing her in her final days. She died on Nov. 2, 1996. After her death, he worked out a deal with Eva’s parents, Hugh and Barbara Cassidy, who lived in suburban Maryland and controlled her estate.

In 1998, Blix released “Songbird.” The collection featured some songs taken from Blues Alley, others recorded by Biondo at his studios.

The record had middling success in most of the United States. But Cassidy’s posthumous career took off when a BBC producer in London got a copy of “Songbird” and began playing a live version of “Fields of Gold” and a studio rendition of “Over the Rainbow.” The phones lit up.

The U.K. was enthralled. An amateur video of Cassidy singing “Over the Rainbow” filmed at Blues Alley was played on BBC-TV’s “Top of the Pops” and quickly became the most-requested video in the program’s history, according to the show’s producers. A handful of gold record singles and millions of CD sales followed.

To take advantage of Cassidy’s reverse British Invasion from the beyond, Blix put out its own version of “Live at Blues Alley,” also in 1998. The Cassidy craze peaked with the BBC putting her interpretation of “Over the Rainbow” on its “Songs of the Century” album in 1999. Sales of her records remained strong throughout Europe for years.

SO, THERE IS DEMAND for new old stuff: Yet, the release of “Nightbird” has sparked discussion of exploitation among band members. The original “Live at Blues Alley” had 12 live tracks. To sweeten the pot for “Nightbird,” Blix Records has added 19 more tracks taped at the Jan. 3, 1996, show, including covers of Aretha Franklin’s “Chain of Fools” and Cyndi Lauper’s “Time After Time.” That’s 31 songs from that evening, plus two more bonus tracks.

McLeod says he feels the real Eva comes out on the Blues Alley tapes. “She could walk on stage and be embarrassed about saying ‘good evening’ or ‘thanks for coming,’ ” he says. “But then the music would start and she’d open her mouth and just nail a song to the wall, and the room’s going crazy, and this little, shy ‘thank you’ would come out. She was the classic introvert.”

There is nevertheless a fairly strong sense among band members that more isn’t always merrier, that releasing everything isn’t the greatest way to pay tribute to Cassidy. They say she had been fighting a cold heading into the Blues Alley gigs, and that on the tapes of the second night you can hear her voice occasionally cracking. (The idea of Cassidy’s voice cracking is positively absurd to many of her fans.)

“At what point do you try to protect the legacy of the artist? I don’t know,” says Williams, who says he can’t help but listen for notes he would play differently on the new recording. “You have on one side a feeling of picking over the bones, and the other argument is the fans want to hear everything.”

But Williams, who now runs a business with Biondo composing and recording music for television and cinema, has been around long enough to know that artistic differences between labels and performers have been around as long as labels and performers. The label always wins.

“So my feeling is you emotionally prepare yourself that eventually everything from Eva is going to be put out,” he says, “and the good stuff will far outweigh the bad.”

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.