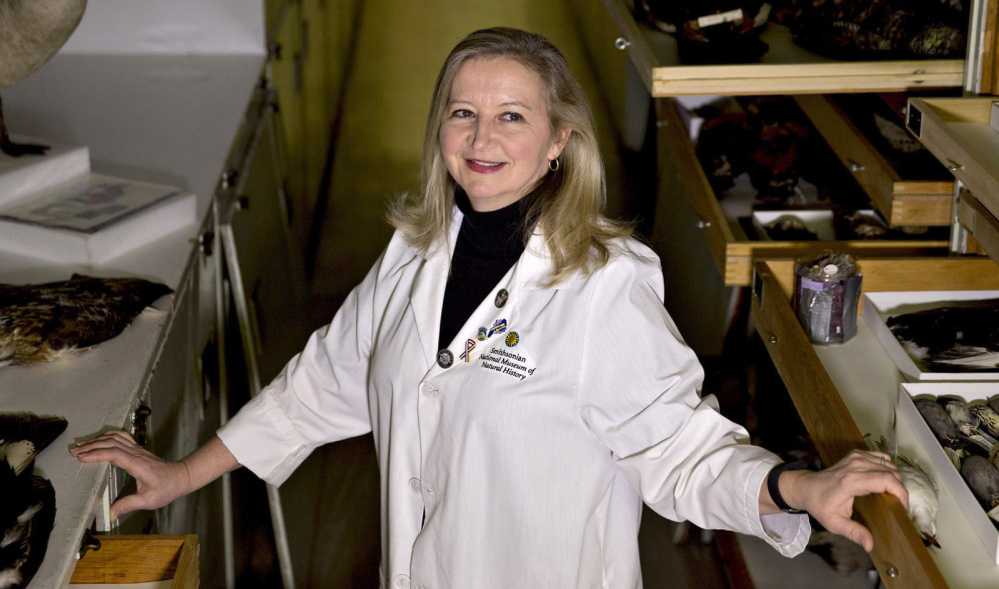

From a drab warehouse beneath the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History in Washington, one of the world’s foremost avian sleuths is trying to solve a mystery.

Working with just a fragment of a black feather found after a jet slammed into a bird in California, Carla Dove tries to identify its species. Based on its size and color, she heads straight to the cabinet holding a preserved 3-foot-tall golden eagle.

“This is a huge bird,” Dove says. Golden eagles average at least 8.6 pounds, more than enough to tear an engine apart or blast a hole through an airliner’s fuselage. She sifts through its black plumage with one hand, holding the broken feather nearby for comparison. Sure enough, the sample is a match.

She’s getting such avian forensics requests more often these days. Seven years after a flock of Canada geese forced a US Airways Airbus Group A320 down on the Hudson River, the number of cases of birds striking planes has risen sharply and some safety advocates say the government isn’t doing enough to prevent what they see as an inevitable catastrophe.

Collisions between airliners and large birds – those most capable of crippling a plane – rose 37 percent between 2000 and 2014, the most recent year statistics are available, according to a Bloomberg analysis of U.S. data. There were 284 such cases in 2014, the most since FAA began collecting records in 1990.

One reasons is bird populations have boomed due to conservation efforts and the elimination of the pesticide DDT, particularly large species that travel in flocks – inherently more dangerous because they can inflict damage to multiple engines.

Canada geese have grown from about 2.6 million in North America in 1990 to 5.7 million last year, according to U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service estimates.

Dove, a forensic ornithologist with a doctorate from George Mason University, sees that every day from her perch at the Smithsonian where she receives feathers and bird remains recovered from planes and runways. In fiscal 2008, her lab received 787 samples from civilian aviation. Last year it got 3,412.

Even with a few wisps of feather, Dove can usually identify at least the class of bird by examining it under a microscope. The Smithsonian now has a DNA library of bird species so it can identify the victim from just tissue samples, known in her trade as “snarge.”

Identifying the species can help authorities direct efforts to target certain bird populations and develop other strategies to cut risk.

She apprenticed under her predecessor, Roxie Laybourne. It was Laybourne who invented feather forensics after a flock of starlings took down an Eastern Airlines plane in Boston in 1960, killing 62. After working by Laybourne’s side, Dove earned a Ph.D. in 1998 and took over after Laybourne died in 2003.

Watching the surge in her caseload has left her frustrated.

“To the industry, this is becoming business as usual,” Dove said. “It’s an accepted risk because they think there is nothing they can do about it. That’s completely wrong.”

The government has acknowledged the threat. New regulations to protect aircraft may be needed to combat the risks, the Federal Aviation Administration said in a June 25 public notice. “The bird strike threat has increased, especially the threat due to larger birds,” the agency said in a notice asking for industry suggestions.

Among the most famous bird strike was the one that came to be known as the “Miracle on the Hudson.” After geese snuffed out both of US Airways Flight 1549’s engines just after leaving New York’s LaGuardia Airport on Jan. 15, 2009, only luck and fast action by the pilots, including Captain Chesley “Sully” Sullenberger, kept it from crashing, according to U.S. National Transportation Safety Board findings.

Some think the increase in strikes may be due to better reporting. Richard Dolbeer, a wildlife biologist who has consulted with the Department of Agriculture and the FAA, said airports are doing a better job controlling wildlife.

The FAA has said it is considering whether to require stronger aircraft structures and lower speed limits at low altitudes for airliners. It also is considering whether helicopters, which fly at lower altitudes where flocks are present, should be hardened against birds.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.