Low fossil fuel prices and shifting government energy policies have combined to threaten the future of Maine’s wood energy industry, along with hundreds of logging and trucking jobs that supply the state’s biomass power plants and pellet mills.

Maine is a national leader in renewable energy, and its vast forests provide low-grade wood that generates more than a quarter of the state’s electricity. But Maine’s free-standing biomass plants can’t run profitably without favorable wholesale electricity prices and state laws that offer above-market rates for renewable power. Today, both of those supports are eroding.

Wood energy is being hit from two directions. One blow is coming from a glut of domestic natural gas, used to generate half of New England electricity, which has lowered rates. It’s great news for utility customers, and it’s providing a new option for pulp and paper mills connected to Maine’s expanding natural gas pipelines. But it’s bad for biomass power.

At the same time, more stringent policies for renewable energy in Massachusetts and Connecticut, where most of Maine’s biomass power is sold, are making less-efficient plants ineligible for crucial rate subsidies.

These changes are taking place as collapsing petroleum prices have sent heating oil to its lowest levels in 12 years. That has led many homeowners with pellet stoves to turn up the oil heat, which today is cheaper than burning pellets. Lack of demand, compounded by the mild winter, led the state’s four pellet mills in January to either stop production or cut way back.

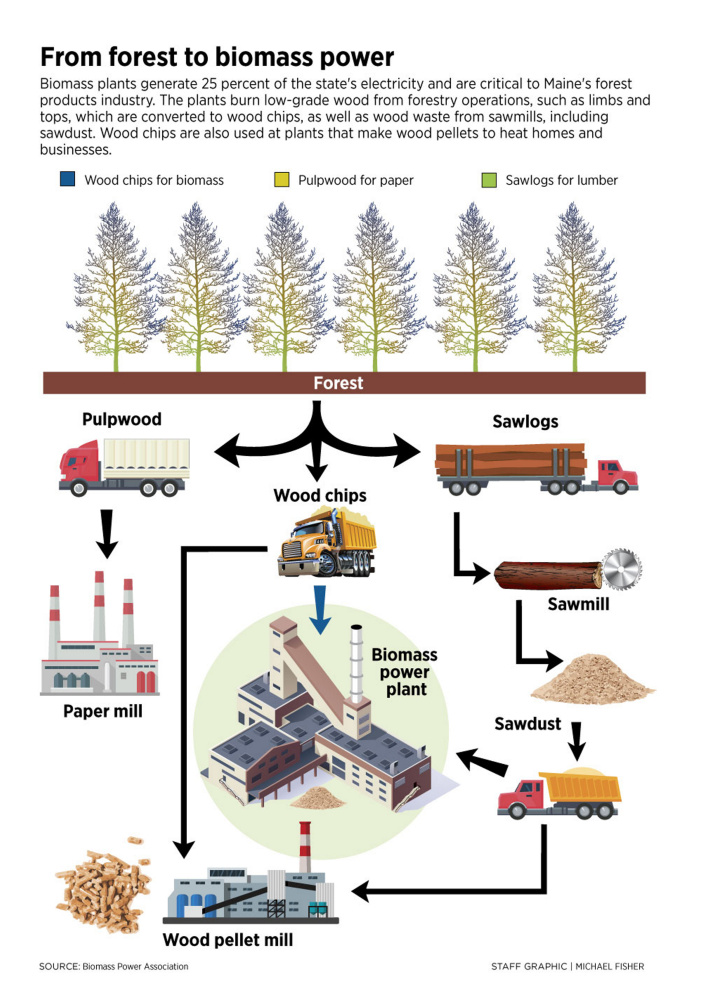

“If the pellet mills go down, and the biomass burners go down and the pulp mills switch over to natural gas, then the woods business is in trouble,” said Bob Linkletter, president of the Linkletter & Sons logging company, as well as the Maine Wood Pellet Co. in Athens. “We’re all interconnected, one way or another. We all use each other’s waste to make a product, to use 100 percent of the tree.”

Those connections already are starting to unravel.

The owner of two biomass plants in West Enfield and Jonesboro, Covanta Energy, said last month it would shut them in March. The four ReEnergy Holdings plants in Livermore Falls, Stratton, Ashland and Fort Fairfield, could follow in 2018. Together, the six plants directly employ 148 workers.

But those jobs represent only a small fraction of what’s at stake.

The six biomass plants spend a total of $115 million a year to purchase 2.5 million tons of low-grade wood that’s harvested and delivered by 900 loggers, truck drivers and other workers. If the plants close, many of these residents who live in job-starved rural communities could be looking for work.

Losing the biomass plants would have a ripple effect on Maine’s forest products industry, which already is shrinking as paper mills close or lay off workers.

The biomass plants provide a crucial market for thousands of tons of sawdust generated by Maine’s sawmills. So do the pellet mills, such as Linkletter’s Maine Pellet Co. plant, which halted production in mid-January. Losing these markets would create a giant waste disposal problem and deprive the sawmills of a source of income that can represent the difference between profit and loss.

The pending crisis has put pressure on Maine lawmakers and Gov. Paul LePage to do something to stem likely job losses this spring, when muddy ground ends the seasonal scramble to get fiber out of the woods. Politicians may face a difficult choice: Ask electric ratepayers to prop up biomass power, or risk losing hundreds of jobs and millions of dollars in investment.

CLOSELY LINKED: BIOMASS, SAWMILLS AND LOGGING

The link between the biomass plants, sawmills and the logging industry could be seen in late January outside the ReEnergy Holdings biomass plant in Livermore Falls.

Inside the gate, the trucks backed onto large platforms that tip the trailers up to empty the chips onto a conveyor and move them to a 50,000-ton stockpile. The fuel eventually will be sent to fire a 39-megawatt generator, capable of lighting 37,000 homes. Five days a week, a similar scene is playing out at Maine’s other biomass plants, which together can generate enough power for 200,000 homes.

The wood taken to the ReEnergy plants is cut to Sustainable Forestry Initiative standards, a third-party certification program that requires loggers to use best forest management practices. Much of the wood comes from logging contractors such as Tom Cushman, a Master Logger and owner of Maine Custom Woodlands in Durham.

In late January, Cushman was thinning a 75-acre woodland properly in Brunswick. To the untrained eye, the wood yard looked like a tangle of tree trunks and branches. But using a grapple crane, Cushman had organized the work area into market categories that illustrated the diversity and value of Maine’s woodlands.

One stack of birch and maple logs would be trucked to a mill in West Paris and turned into hardwood chips for the Catalyst Paper Co. mill in Rumford. Other stacks would be cut and split for firewood. A stack of pine logs would go to the Hancock Lumber sawmill in Bethel. Until last year, pine tops unsuitable for lumber became pulp for the Verso paper mill in Jay. But Verso shut down that part of the mill operation last year, prior to filing for bankruptcy protection in January. With the higher-value pulpwood market gone, the softwood is going to biomass plants.

Cushman also created small mountains of branches and limbs. It has no market value other than biomass.

“Small landowners want the tops of the trees chipped,” he said. “They don’t want piles of brush out in the woods. They want a clean job.”

Operating the crane, Cushman grabbed 40-foot-long trees and fed them into a powerful chipper, which spit 68,000 pounds of chips into a box trailer in roughly 20 minutes. Ten times a day, a full truck left Brunswick for the 60-mile trip to ReEnergy in Livermore Falls. Cushman estimated that he hauls 1,500 tons a week to the power plant.

Cushman has 21 employees and was working with a crew of nine people to harvest the Brunswick woodlot. Operators and drivers are paid $50,000 or more a year. His company buys diesel fuel, tires and other equipment to keep the trucks and logging machinery moving.

“We support 21 families,” he said. “That’s a big deal. I take it really seriously.”

The threat to the biomass plants has Cushman worried. Culling and trucking biomass, he said, represents half his income.

“I don’t know that I’d be in business any longer without biomass,” he said.

SAWMILL WASTE ISN’T WASTED

Business also is threatened at the PalletOne/Isaacson Lumber Co. sawmill in Livermore Falls.

The recovering national economy has created a high demand for pallets, on which many products move. The pallet mill now has 160 workers who earn more than $40,000, plus benefits, according to Donnie Isaacson, the vice president. He sources hardwood logs from as far away as Millinocket and Kittery.

But as production grows, so does wood waste. The mill generates 40,000 tons a year of bark and sawdust and 20,000 tons of wood chips. The chips are sold to the Verso paper mill in Jay and the Sappi paper mill near Skowhegan. Most of the bark and sawdust go to the ReEnergy biomass plant, where they are worth $20 a ton.

“If there was no biomass, the sawmill industry in the state would be in big trouble,” Isaacson said. “Beyond a place to get rid of tons of waste wood, it has a huge value. It’s the difference between profit and loss.”

Isaacson said he is hopeful that state officials will see the value of the wood energy industry and take steps to help save it.

“I think the government has to get involved,” Isaacson said. “There are a lot of jobs at stake here.”

HIGH OIL PRICES FED BIOMASS DRIVE

In calling for government help, Isaacson is aware that Maine’s biomass plants are a creation of government.

They exist because of federal and state laws passed during the late 1970s and early 1980s, when high-priced imported oil was killing the economy. The laws ordered utilities to buy a share of their electricity from renewable energy plants, and allowed them to pay a higher rate. Eleven biomass plants were built in Maine.

But when oil prices unexpectedly crashed in the 1990s, utility customers were saddled with millions of dollars in above-market power costs. The outcry led utility regulators to reverse course and order power companies to buy out the highest-priced contracts. The process led several biomass plants to close, although some later opened again under new ownership.

In Ashland, the sister plant of the one in Livermore Falls was shut in 2011, but came back on line when ReEnergy bought it from a previous owner in 2014. The Ashland plant is located in a complementary cluster of forest products businesses – a sawmill, a pellet producer and a shingle maker. Less than 18 months ago, politicians came to praise the development, including LePage, who symbolically flipped a switch on a signboard bearing his economic development slogan: “Open for business.”

Now LePage and other Maine policymakers will have to decide how to keep Maine’s biomass plants open for business.

The first priority is the two Covanta plants in West Enfield and Jonesboro. They rely on Renewable Energy Certificates that make up roughly half the generating income they receive from Massachusetts utilities. But as of last month, the 29-year-old plants don’t qualify for the certificates under new efficiency and wood harvesting standards. Meanwhile, low wholesale electric prices have undermined the plant’s second source of income.

“The bottom line is that the cost of energy is really low and it’s not sufficient to cover the cost of operation,” said James Regan, a Covanta spokesman.

Forty-four people work at the two plants, which are supplied by roughly 200 loggers and truckers.

Regan declined to specify exactly what would be needed to keep the plants open past March.

“It’s hard to say,” he said. “This happens with some frequency in the biomass industry. I know people are advocating for us and hopefully something can be done.”

The four other biomass plants, owned by ReEnergy, rely on above-market rates in Connecticut, which is in the process of changing its renewable energy rules. One proposal is to phase out older biomass plants to create incentives for newer, cleaner renewable generators.

“We may face a similar issue as Covanta in 2018,” said Sarah Boggess, a ReEnergy spokeswoman.

To head that off, Boggess, members of the Professional Logging Contractors of Maine and other wood energy advocates have been in talks with the LePage administration and legislators. They have prepared a fact sheet estimating 1,300 jobs are linked to the six plants, with each plant creating between $10 million and $20 million in economic activity. On top of that, the plants generate 300 megawatts of power from renewable energy and promote sustainable forestry.

The industry has outlined a handful of general actions that Maine could take to help save the plants, including setting up power purchase agreements with consumers and asking the Maine Public Utilities Commission to require or encourage biomass contracts up to a certain percentage of the state’s energy load.

It’s not clear how LePage will react to these concepts.

On one hand, the governor has long been critical of any policies that raise electric rates, arguing that they make Maine less competitive for business. At the same time, he has been unable to prevent the forest products industry from shedding hundreds of jobs, as paper mills shut down in East Millinocket, Bucksport, Lincoln and Old Town.

In his State of the State letter this month, LePage sent a mixed message about biomass. Criticizing “socialists” for subsidizing wind and solar power, he voiced support for wood energy and the jobs associated with it.

“Let’s help our economy and all Mainers,” the governor wrote, “rather than artificially limiting sources of inexpensive energy.”

Asked to explain the governor’s comments, Patrick Woodcock, LePage’s energy director, stopped short of saying that LePage would acquiesce to above-market energy contracts, but that the concept of long-term contracts approved by the PUC is on the table.

“We’re open to discussing that,” Woodcock said. “We’re looking at a policy that makes sense for the biomass industry and the ratepayers.”

Weighing benefits should include economic impact, not just electric rates, according to Rep. Jeff McCabe, D-Skowhegan. McCabe is the House majority leader and has two paper mills in his district – the Sappi mill and Madison Paper Industries, which announced last month that it was cutting its production schedule.

“We need to have a discussion about the benefits of home-grown energy,” McCabe said. “We spend a lot of time talking about Canadian power and natural gas, and here we have Maine-based power and we should be doing all we can.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.