Guitar great Tommy Emmanuel grew up idolizing Chet Atkins, the country legend credited with helping create “The Nashville Sound” of the 1960s.

So Emmanuel did not take it lightly when Atkins told him one day more than 35 years ago, in a Nashville recording studio, that he was about to meet “the greatest guitar player walking the earth today.”

“We went upstairs and I could hear a guitar playing. We opened the door and there was Lenny Breau,” said Emmanuel, 60, Guitar Player magazine’s acoustic player of the year in 2010. “Harmonically, his music was more sophisticated than anything I’d ever heard. He was doing stuff nobody had done yet.”

Breau, who was born in Maine but lived much of his life in Canada, died mysteriously more than 30 years ago at the age of 43. He was found strangled in a Los Angeles swimming pool in 1984, and no one was ever charged. But his legacy continues to grow.

Last year, an album of Breau’s music titled “LA Bootleg 1984” was nominated for best solo jazz album at the Juno Awards, Canada’s version of the Grammys. A restaurant named Lenny’s opened in Westbrook in February on the site of the small Event Records label, where Breau once recorded. In the years since Breau’s death, there have been articles and books written about him, as well as documentary films focused on him, plus scores of online videos that have allowed a new generation of musicians around the world to discover Breau’s music.

Breau was never a household name, never a star. His biggest bursts of public fame came during his work on TV shows in Canada in the 1960s and from a couple of albums he recorded for RCA in the late 1960s while working with Atkins. But he remains a legend among guitarists for his ground-breaking style and sense of creativity.

Breau used all five fingers on his right hand to play individual strings, much the way a piano player uses individual fingers to strike single keys, instead of playing one string at a time the way a player using a pick might do. Breau’s style, combined with his mastery of complex chords and harmonics, continues to astonish guitarists around the world.

“He had such interesting chords, over the melody,” Emmanuel said. “Others might have had a similar style, but he was the only one wired the way he was.”

Emmanuel and Atkins are just two of the dozens of guitar greats who have cited the Auburn-born Breau as a singular talent and a major influence on guitar playing over the last 50 years. George Benson, Pat Metheny, Andy Summers of The Police, and Randy Bachman of Bachman-Turner Overdrive and The Guess Who are a few others.

Breau played mostly jazz and had a devotion to creativity and innovation that made it impossible for him to happily do anything considered mainstream. Plus, he battled drugs, including heroin, for long stretches of his adult life.

Atkins died in 2001, but in an interview for the 1999 documentary film “The Genius of Lenny Breau,” he said of Breau, “Lenny was one of those guys who was a genius at what he did, but that was all he could do. He could not take care of himself, and we all knew it.”

‘HE HEARD EVERYTHING DIFFERENT’

Breau was born in Auburn into one of Maine’s best-known musical families. His father, Harold Breau, was a country musician and singer who performed under the name Hal Lone Pine. He met and married Breau’s mother, singer Betty Cody, and together they toured New England and played on local radio stations. By the early 1950s, both were signed to RCA and recorded solo songs and duets. A couple of Cody’s songs, “Tom Tom Yodel” and “I Found Out More Than You Ever Knew,” got considerable radio play. Both husband and wife are members of the Maine Country Music Hall of Fame.

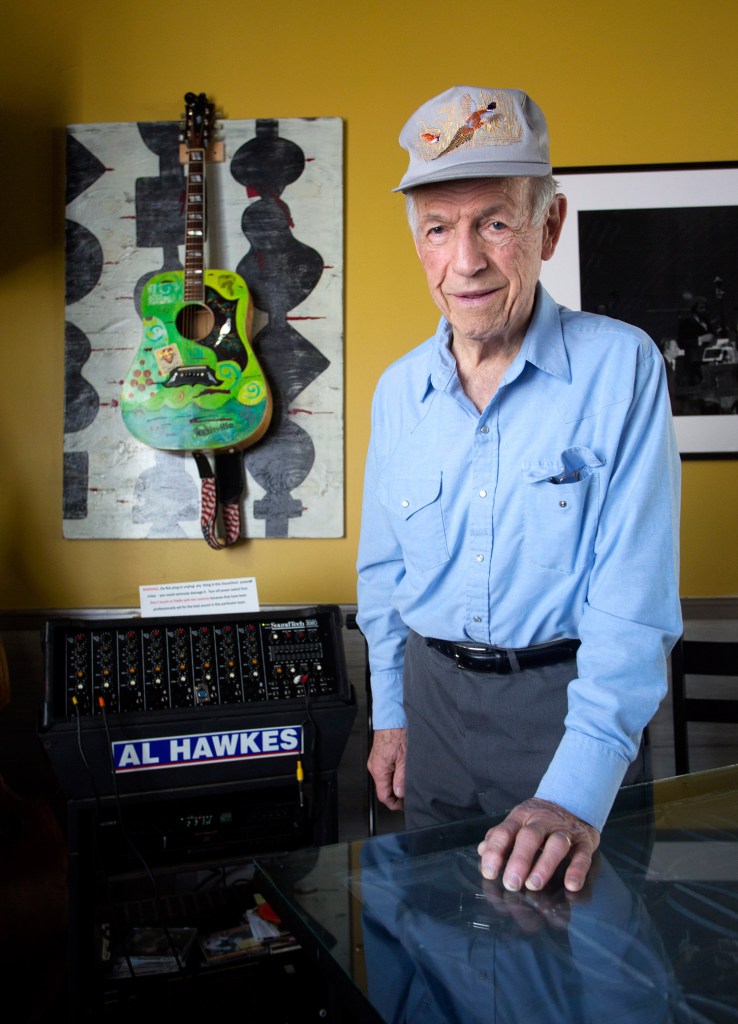

By the early 1950s, the young Breau was playing in the family band and was lead guitar by the time he was 14. Long-time Maine country musician Al Hawkes was running a small record label called Event Records at his TV repair shop in Westbrook when he first met Breau. Breau’s parents had come in to record and brought their son with them.

“I was shocked when I heard him play. I said to his mother ‘How old is that boy playing the guitar?’ and she said he was 14,” said Hawkes, 85. “I thought, wow, I’ve got to get him back here. So I started using him as a session musician.”

What made Breau stand out at that age was “his brain,” Hawkes said. “He was always composing, and he heard everything different from everyone else.” When rehearsing a song, Breau would often play a guitar part exactly the way Hawkes wanted it, then play it a completely different way when it came time to record.

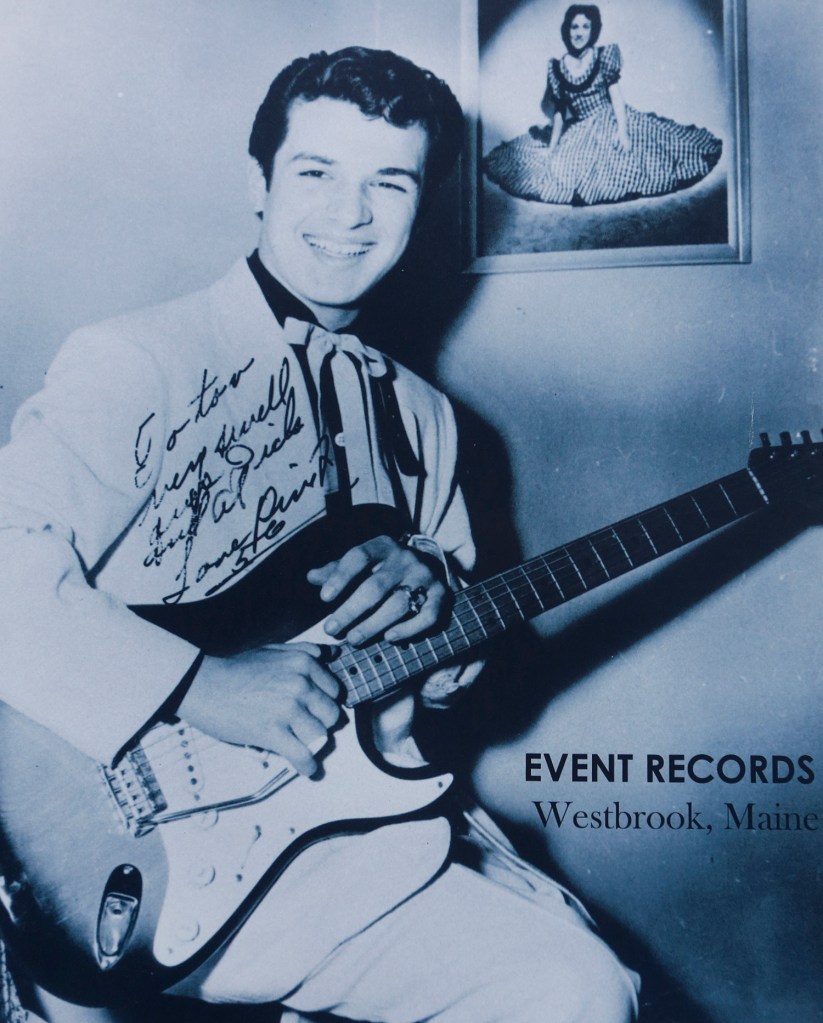

Though Breau was later known for playing jazz, with some flamenco guitar influence, as a teen he was playing country and rockabilly. At Event Records, he played on the rockabilly hit “Baby Baby” by Curtis Johnson and also played guitar on early recordings by Dick Curless, a Mainer who went on to have several hit records on the country charts in the 1960s and ’70s.

Breau’s family moved to Winnipeg, Manitoba in Canada in the late 1950s, performing around the area and on radio. While Breau was playing country music with his family, he was experimenting with jazz and other forms. He was once slapped on stage, by his father, for ending a song with a jazzy flair, said Breau’s younger brother Denny Breau, a professional guitarist who lives in Lewiston.

Breau began playing on his own as a teenager. When his family moved back to Maine, he stayed in Winnipeg, playing in clubs and on Canadian TV shows. He had his own show for a while in the mid-’60s, “The Lenny Breau Show,” which featured singers starting out with a fairly straight cover of a popular song, like “Downtown” by Petula Clark, until Breau took over with his own, barely-recognizable, jazz version of the song.

A recording of Breau on TV from this period made its way into the hands of Atkins, who was vice president of the RCA record label’s Nashville recording division. Breau made two albums at RCA, “Guitar Sounds from Lenny Breau” and “The Velvet Touch of Lenny Breau,” but neither had mainstream appeal. Friends and family say that Breau was driven to create but never driven to make money or achieve fame.

“He was a true Bohemian who just lived his art and seemed disinterested in a lot of other things,” said Breau’s daughter, Emily Hughes, of Calgary, Alberta. “He was mastering his instrument and a lot of other things suffered.”

Hughes was raised by her mother, Canadian singer Judi Singh, and didn’t see Breau much growing up. She said her mother wanted to protect her from the drugs and accompanying havoc that was a strong presence in Breau’s life.

In 1999, Hughes made a documentary film called “The Genius of Lenny Breau,” which featured interviews with Atkins, Benson and many other musicians, and allowed Hughes to learn about her father. She heard several stories that emphasized his singular focus on music, to the detriment of other parts of his life. He rarely drove a car, for example.

“Everybody took care of him and escorted him around,” said Hughes.

In 1973, Breau was arrested for possession of heroin in Winnipeg and was given two years probation. Later in the 1970s, he sought help at a drug rehabilitation facility. He worked in Nashville, Maine and Los Angeles in the 1970s, and released a half dozen albums between 1978 and 1984. He also taught guitar master classes, but remained largely unknown except to other musicians.

“He was in and out (of periods of drug use) and that’s probably one of the reasons he never really made it,” said his brother, Denny Breau, 63, of Lewiston. “I think the pressure drove him to escape.”

MYSTERIOUS DEATH, LEGEND GROWS

On the morning of Aug. 12, 1984, Breau called his mother in Maine, from Los Angeles, saying he needed to escape a home life that had become unbearable. He had married singer Joanne Glasscock, nicknamed Jewell, in 1980.

In an interview with the Press Herald then, Breau’s mother, who died in 2014, recalled him saying, “I’ve got to get away and make my life over.”

He was found dead later that day in the rooftop swimming pool at the apartment building where he lived, with his wife and their 3-year-old daughter, Dawn Rose Marie. A coroner’s report listed the cause of death as strangulation. But police never charged anyone.

No working phone number could be found for Jewell Breau, to seek comment for this story.

Breau’s influence as a musician has seemed to grow over time, thanks largely to the internet. Videos of him playing on Canadian television, or giving master classes, or playing with Atkins live on on YouTube and elsewhere. Hughes says she hears from new Breau fans all over the world. She recently received a Breau tribute CD made by a musician in Paris. An online video clip of Breau playing, posted on her website, got 30,000 hits in Russia in one month. She’s considering another documentary film on her father, focused on his influence on a new generation of musicians and fans.

Denny Breau said what made his brother’s guitar style stand out, especially in the 1950s and ’60s, was that he approached his instrument like a piano. He played individual strings with individual fingers, the way a piano player strikes keys. One of his biggest musical influences was jazz pianist Bill Evans. He was also a student of the percussive flamenco style of guitar playing.

Breau would use his thumb to play a bass line, his first and middle finger to play chords, and his ring finger and little finger to play melody and improvise.

“If you just listen without seeing him, it sounds like two different guys,” said Denny Breau, also a professional guitarist. “The fact that people are still listening to him, studying him, doesn’t surprise me. There’s still nobody even close to him.”

Breau’s music has continued to reach new audiences largely thanks to Bachman, who was a teenager in Winnipeg when he first heard Breau play.

Bachman was 15 and a budding guitarist when he started hanging around with Breau, trying to learn all he could. Bachman would achieve pop music success in the late ’60s and early ’70s as guitarist for the rock band The Guess Who. He wrote or co-wrote several of the band’s hits, including “These Eyes,” “Laughing” and “American Woman.” Later in the 1970s, he had more rock hits as a founder of Bachman-Turner Overdrive, including “Takin’ Care of Business” and “You Ain’t Seen Nothing Yet.”

In an interview with the Toronto Star in 2012, Bachman said of his long music career: “I’m just doing what I’ve wanted to do since that day I was 15 and heard Lenny Breau play the guitar.”

Over the years, Bachman has collected thousands of hours of Breau’s music and has issued some previously unreleased recordings on his Guitarchives label. One of those was an album called “LA Bootleg 1984,” released in 2014 and nominated for a 2015 Juno Award. The album includes Breau recordings made at Donte’s, a Hollywood jazz club, in June 1984.

In the 1998 Bachman also released an album called “Lenny Breau: Boy Wonder” which included country-tinged songs recorded by Breau at Event Records in Westbrook, when Breau was just 14 or 15 years old.

Hawkes remembers that when Bachman first called him to buy the recordings, made in the mid-50s, he was hesitant about the price. Bachman hung up without agreeing to anything, then called Hawkes back later that day, saying he just had to have those recordings.

“He was able to get Lenny’s music out to a lot of people, so I give him credit for that,” said Hawkes, sitting in Lenny’s restaurant in March.

The new Lenny’s restaurant, an upscale pub with room for live music in one corner of the room, is in a building on Route 302 that Hawkes once used as a studio and to sell stereo equipment. While playing and recording music for years Hawkes was also an electronics technician and TV repairman, and the 13-foot-tall TV repairman sign he built in 1962 still stands watch over the property.

Hawkes used a building attached to what is now the restaurant as his Event Records studio. That’s where Breau recorded as a teenager. Hawkes sold the buildings a few years ago to Portland entrepreneur and music fan Bill Umbel. When considering names for the new eatery and music venue, Lenny’s struck him. Hawkes provided him with dozens of pictures of Breau, that are scattered through out the restaurant.

There is also text on the wall explaining who Breau was, when he lived, and why his guitar style influenced so many.

“The fact that people here in Maine can come here and find out about Lenny is just great,” said Hawkes, who lives next door to the new restaurant. “I think he deserves the recognition.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.