The name of PhoPa Gallery is a play on photography and paper, and the biting French phrase for a “false step.” The two-person show, up through May 28, of works by James Marshall and Daniel Anselmi steps into new ground for the gallery. But does it find a true path?

Marshall’s work is silvery sculpture – and sculpture is not common at PhoPa. Anselmi’s work leans heavily on elegantly loping paper-loving collage, but he now appears at PhoPa as an artist with his eye on two of the 20th century’s greatest painters: Picasso and Matisse.

Picasso and Matisse (who were famous for not being able to be in the same room with one another) come together with paper: Picasso as co-creator of cubism – where collage was invented – and Matisse as the grand master of paper painting with his widely beloved paper cut-outs. Anselmi covers the range of their work within the four modes of his collage paintings: a suite of Matissian color shape-oriented collages, a suite of late-cubist style paper-sized compositions, a group of ink drawings that look like small sketches for the large paintings of Abstract Expressionist Franz Klein, and a pair of large painterly compositions that were part of a 2015 show in Belfast.

I preferred Anselmi’s smaller pieces to the large, loose works, but the latter seemed to release him from his typically insistent tonal coherence. They are a welcome inclusion because they usher in a sparky grittiness. But they do something else, as well: The large works force us to consider their literal scale. This was a rare thing in art before the 1950s, except in sculpture and Matisse’s cut-outs.

Anselmi’s pair of large collages makes the leap to connect his work to Marshall’s sculpture. To be sure, it is no accident: Anselmi’s “King Arthur,” an orange and red field of forms with a bit of yellow to frame a tangerine form under a white crown, and “Sir Lancelot,” an effervescent field of poppy gray silver circles and three mustard marshal stripes over a fleshy pink ground, are surrounded on all sides by Marshall’s work.

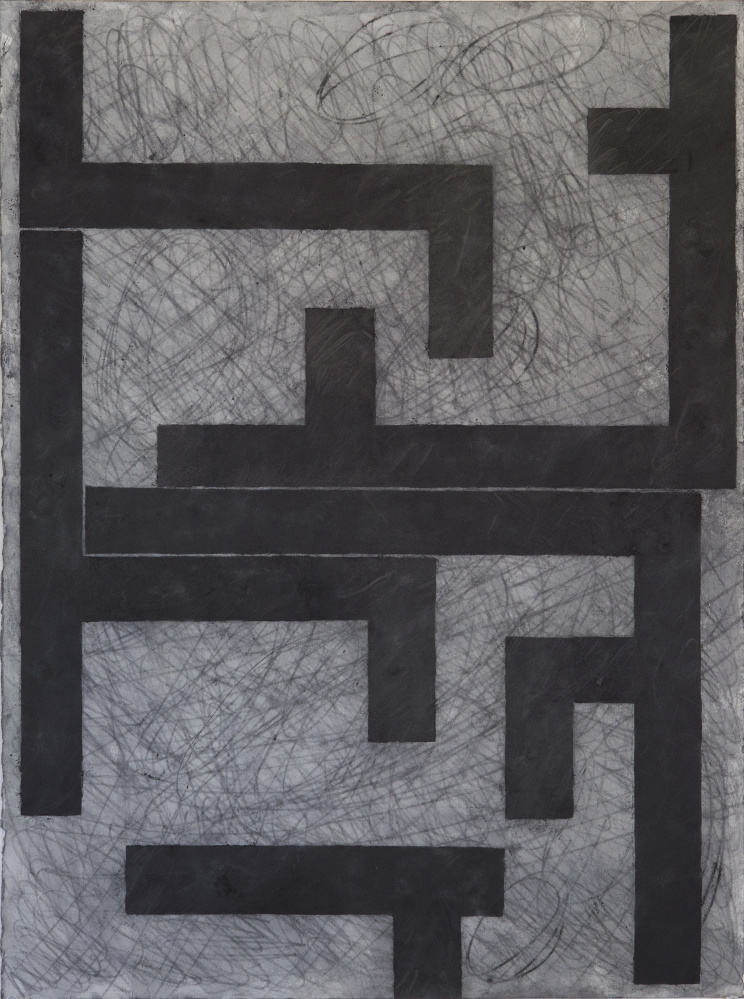

Marshall’s works tie to the gray and reflective play in particular because they are made of graphite: Marshall makes sculpture from paper bags by repeatedly dipping them in a personal recipe of glue and graphite, and placing them together variously. “The Cart,” for example, is four bags together (in a vague dog shape) with the bow handles of the two on the bottom playing the role of cart wheels. “The Four Quadrants” spirals out with a radial motion as the four bags create something like a tilted, radial “#” shape.

While “Four Quadrants” is an unusually strong and self-possessed sculptural object, the wall piece “Quintet” – five long narrow bags, one above the other, creating a single piece with long, skinny and deep shelves – is the boldest in the show. It takes on and discards the seminal minimal wall works of Donald Judd and others with a physical humility and a razor-like sculptural and conceptual acumen. Moreover, “Quintet’s” placement on a bit of jutting wall plays up its assertive gesture into the space of the gallery, almost blocking the path to Camelot.

Marshall’s most complete sculptural work is “Muse,” six bags end to end. While the title hints at a recumbent figure, “Muse” steps up at right angles on one end and curves subtly into space at the other. I would love to see that work on a large floor with a lot of space to itself.

When paired with Anselmi’s cubist-like collages under the theme of “Paper Work,” I find it practically impossible not to consider Marshall’s structures in the light of Picasso’s paper sculptures, like his 1912 guitar, which I am not alone in considering one of the most important sculptures ever made.

Anselmi’s work, in the presence of Marshall’s, gains a spatial sense not only of shapes and value contrasts but of color. Ironically, the spatial color sense is more muscular precisely because Anselmi has leaned away from color as aesthetic tonality and more toward charcoally darks. His “As I see It II,” for example, follows a white, yellow and fleshy pink tract through a dark architecture of charcoal black. While the shapes are Matisse cut-out-like, the contrast with black looks to other moments of Matisse’s boldest painting when he was deepest in unfriendly competition with his rival, Picasso.

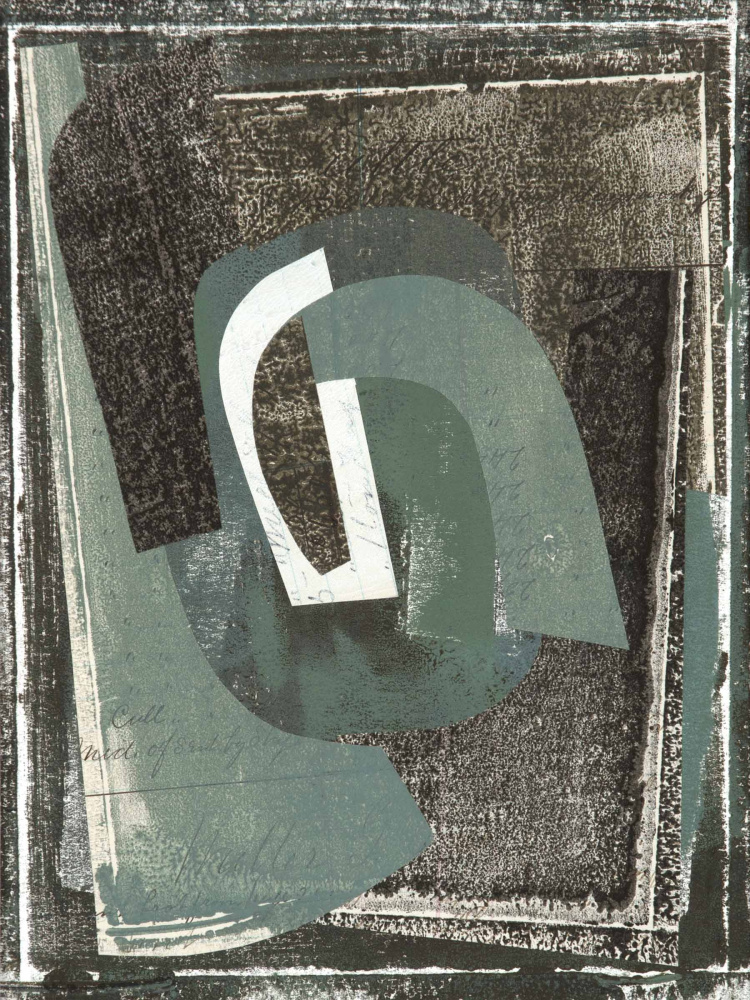

Anselmi’s “Monhegan Series F5,” on the other hand, relies on cubist page-logic with echoes of edges and graphic forms that seem to hide in textured layers, and then a final and decisive punctuation of a white “G” form near the center of the otherwise dark ground. This work delivers a subtle sense of contrarianism by looking to the textures and conceptual details of cubism but then finishing with bold bits of Matissian form.

To be certain, Marshall and Anselmi did not set out to reference the Matisse versus Picasso battle that defined much of the last century’s art. But, however they were matched together, their work combines for undeniable sparks and excitement. It is the strongest and most handsome show I have seen in PhoPa’s swanky little space. And it is one of the best shows I have seen in Maine in a long time – smart, visually rich and thoroughly enjoyable.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.