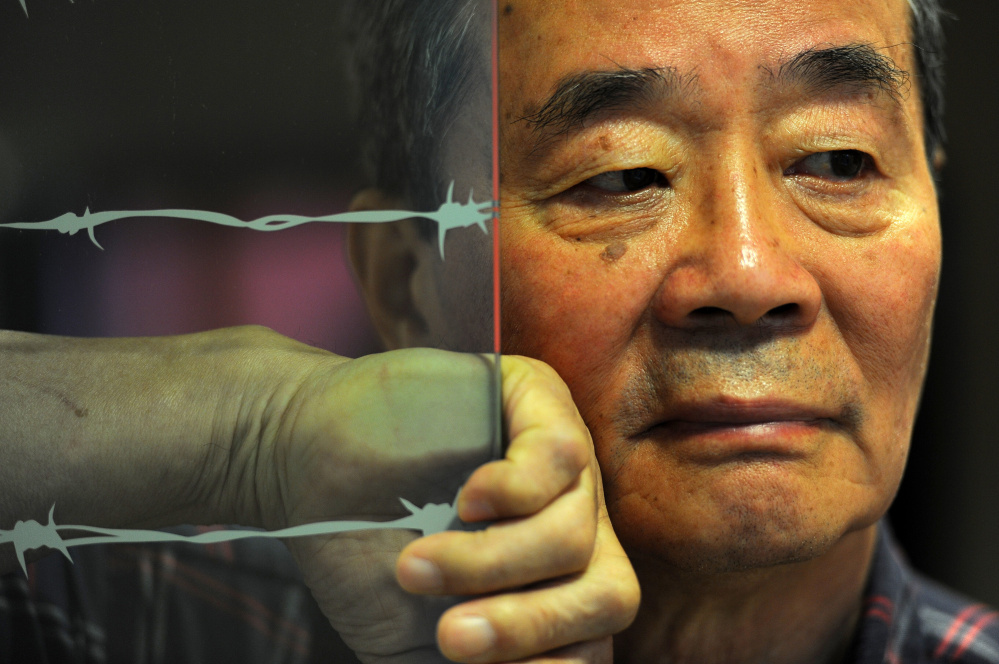

Harry Wu, a Chinese dissident who mounted an international campaign to expose the horrors of his country’s laogai labor camps, where he endured 19 years of captivity as an alleged counterrevolutionary, died Tuesday while vacationing in Honduras. He was 79.

Ann Noonan, a board member of the Laogai Research Foundation, founded by Wu in 1992, confirmed his death and said she did not know the cause.

Wu settled in the United States in 1985 after a ghastly odyssey in the Chinese prison system in which he withered to 80 pounds, was worked nearly to death and survived, in part, on food that he foraged in rats’ nests. His offense, as a university student in the years after the Chinese Communist Revolution, had been to criticize the 1956 invasion of Hungary by the Soviet Union, the world’s other major Communist power.

SELF-DESCRIBED ‘TROUBLEMAKER’

Wu was imprisoned in 1960. After his release in 1979, three years after the death of Communist leader Mao Zedong, he built a profile as a human rights activist and self-described “troublemaker” who repeatedly slipped back into China to gather undercover footage of the prison camps.

The footage aired on the CBS news magazine “60 Minutes” and on the BBC in the 1990s. With those reports, Wu helped draw widespread attention to Chinese practices of using forced labor to produce exports – among them wrenches and artificial flowers ultimately banned by the United States – and harvesting organs from executed prisoners. According to his research, more than 50 million prisoners passed through the system over 40 years.

He was at times compared to Alexander I. Solzhenitsyn, the Nobel Prize-winning Russian writer who documented the atrocities of the Soviet gulag. Wu described the loagai prisons, which purported to deliver “reform through labor,” as the Chinese gulag and said he would not rest until the word loagai appeared in “every language dictionary in the world.”

He testified before Congress, lectured on university campuses, wrote books and established the Laogai Research Foundation and Laogai Museum, both based in Washington, to educate the public about the Chinese labor camps.

In an interview with the Los Angeles Times, he described them as “the cornerstone of the Chinese Communist dictatorship and the machinery for crushing human beings physically, psychologically and spiritually.”

By his account, Wu stole from prisoners and collaborated with police to survive in prison.

“I became an animal,” he told The Washington Post. “If you are human, you have feelings and suffer because you are always thinking and wishing about what cannot be. But animals never think, never wish. Unless you are an animal, you cannot survive.”

He endured solitary confinement and suffered a broken back when a runaway cart struck him in a coal mine. When his captors discovered that he had hidden Western books, including Victor Hugo’s “Les Misérables,” they broke his arm. He once attempted suicide by refusing to consume the meager provisions the prisoners received.

A turning point came with the death of a fellow inmate and friend. Wu clutched his body as it was carried to a grave, he recounted in a memoir, “Bitter Winds” (1994), coauthored with a journalist, Carolyn Wakeman.

“Human life,” he recalled thinking, “has no more importance than a cigarette ash flicked in the wind. But if a person’s life has no value, then the society that shapes that life has no value either. If the people mean no more than dust, then the society is worthless and does not deserve to continue. If the society should not continue, then I should oppose it.”

UNSTINTING IN HIS ADVOCACY

Unstinting in his advocacy, Wu at times attracted controversy for the stridency of his campaign, which complicated tenuous U.S.-Chinese relations in the years after the Tiananmen Square crackdown. He was arrested after entering China in 1995, a development condemned by both houses of Congress, shortly before first lady Hillary Clinton planned to travel to Beijing for a U.N. conference on women.

Wu was detained for 66 days and convicted of espionage, but he was expelled in time for the first lady’s trip.

Asked why he returned so many times to China, when the danger to him was so great, he replied, “I cannot turn my back to my homeland.”

“My parents’ graveyard, my former inmates’ graveyards are over there,” he said. “That piece of land is full of my blood and tears.”

Wu Hongda, one of eight children, was born in Shanghai on Feb. 8, 1937. His father was a banker, and his mother died when he was young.

Wu attended a Jesuit school, where he received the name Harry, and later pursued university studies in geology. As a student, he took part in the Hundred Flowers campaign in which Mao encouraged citizens to air grievances with the party.

When party leaders received more criticism than they wished to hear, they cracked down on so-called counterrevolutionary rightists. Among them was Wu. His stepmother committed suicide during his captivity.

After his release, Wu worked in China as a geology lecturer. In 1985, he came to San Francisco, where he was homeless for a period before finding work in a doughnut shop. In time, he established himself through scholarly associations with the University of California at Berkeley and the Hoover Institution at Stanford University.

In 1994, he became a U.S. citizen, taking the name Peter Hongda Wu. His books included “Laogai: The Chinese Gulag” (1992) and “Troublemaker” (1996), coauthored with former New York Times sports columnist George Vecsey.

Wu was married several times, most recently to Ching Lee. Their marriage ended in divorce. Survivors include a son, Harrison Wu of Vienna, Virginia.

“I want to enjoy my life,” Wu told the Los Angeles Times in 1995. “I lost 20 years. But the guilt is always in my heart. I can’t get rid of it. Millions of people in China today are experiencing my experience. If I don’t say something for them, who will?”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.