WASHINGTON — Getting stitched up by Dr. Robot may one day be reality: Scientists have created a robotic system that did just that in living animals without a real doctor pulling the strings.

Much like engineers are designing self-driving cars, the research is part of a move toward autonomous surgical robots, removing the surgeon’s hands from certain tasks that a machine might perform all by itself. No, doctors wouldn’t leave the bedside – they’re supposed to supervise, plus they’d handle the rest of the surgery. Nor is the device ready for operating rooms.

But in small tests using pigs, the robotic arm performed at least as well – and in some cases a bit better – as some competing surgeons in stitching together intestinal tissue, researchers reported in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

The project is “the first baby step toward true autonomy,” said Dr. Umamaheswar Duvvuri of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, a head and neck surgeon and robotic specialist who wasn’t involved with the new work.

But don’t expect to see doctors ever leave entire operations in a robot’s digits, he cautioned.

The STAR system works sort of like a programmable sewing machine.

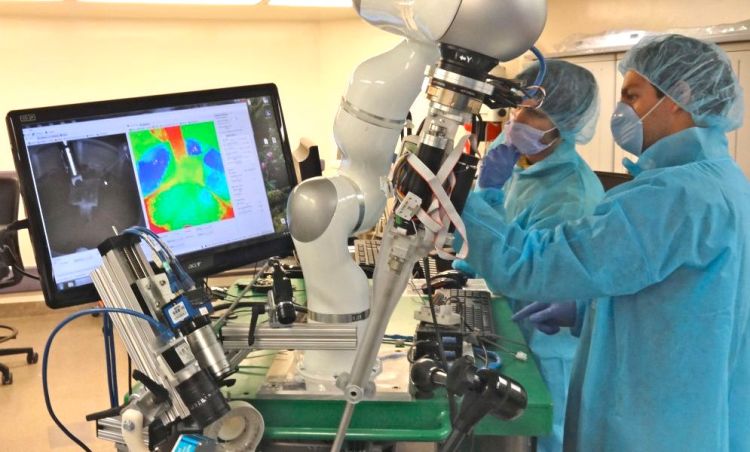

Kim’s team at Children’s Sheikh Zayed Institute for Pediatric Surgical Innovation took a standard robotic arm and equipped it with suturing equipment plus smart imaging technologies to let it track moving tissue in 3-D and with an equivalent of night vision. They added sensors to help guide each stitch and tell how tightly to pull.

The surgeon places fluorescent markers on the tissue that needs stitching, and the robot takes aim as doctors keep watch.

Now the test: Could the STAR reconnect tubular pieces of intestinal tissue from pigs, sort of like two ends of a garden hose?

Using pieces of pig bowel outside of the animals’ bodies as well as in five living but sedated pigs, the researchers tested the STAR robot against open surgery, minimally invasive surgery and robot-assisted surgery.

By some measures – the consistency of stitches and their strength to avoid leaks – “we surpassed the surgeons,” said Children’s engineer Ryan Decker.

The STAR approach wasn’t perfect. The STAR had to reposition fewer stitches than the surgeons performing minimally invasive or robot-assisted suturing. But in the living animals, the robot took much longer and made a few suturing mistakes while the surgeon sewing by hand made none.

Kim, whose team has filed patents on the system, said the robot can be sped up. He hopes to begin human studies in two or three years.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.