One of the outstanding dramas of TV’s golden age ends Sunday, and there’s a lot to talk about. But then, there always was with “The Good Wife.”

“You and I should talk,” in fact, was possibly the most repeated line of dialogue over seven seasons and 154 episodes. TV’s most densely packed drama was also its most densely worded drama at times. Often unfolding in courtrooms, with a judge and that baleful reminder above his head (“In God We Trust”) as witness, the setting was usually just a rarefied and expensively appointed law office, with light filtering in from between the horizontal blinds. (The show was set in Chicago, but that was actually New York light. Specifically, Brooklyn, where one of the city’s most esteemed homegrown productions was shot.)

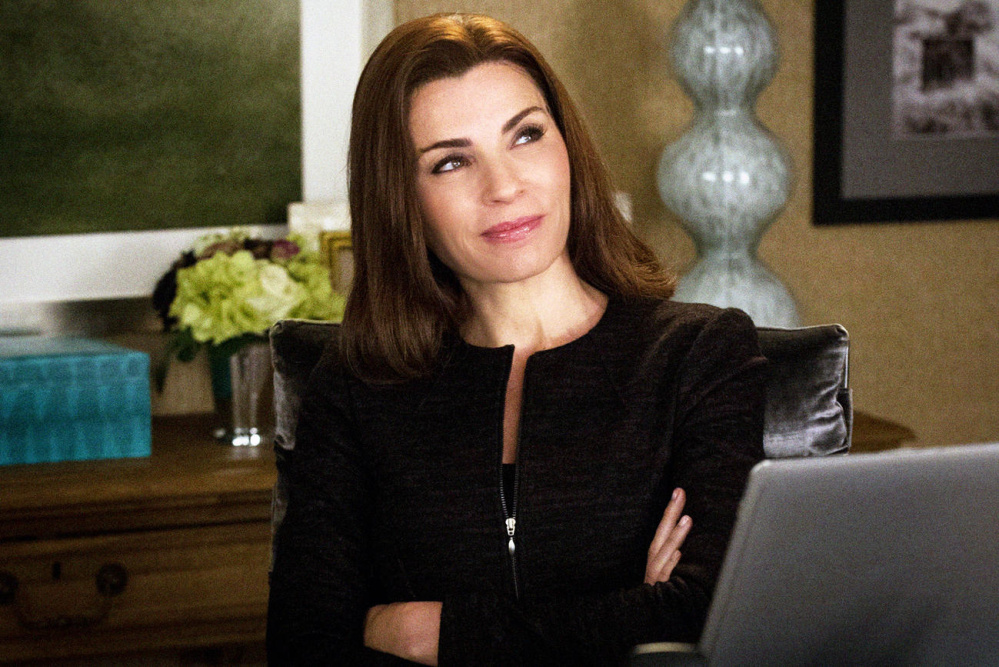

Plots were hatched (or demolished) in those offices, while hearts were laid bare (or shredded). “The Good Wife” leaves behind a great deal, and not just aggrieved fans. There’s an enormous amount of back story and shared history about to come to an end – far too much to remember or sort out in the short time left. Instead, let’s talk about what mattered most over these seven seasons, or rather who: Alicia Florrick (Julianna Margulies).

“The Good Wife” arrived in 2009 just as two other future classics were in ascendance, “Mad Men” (2007) and “Breaking Bad” (2008). All three had the same preoccupations and themes – troubled protagonists, midlife crises, the uncertain terrain of the American dream. The workplace may have often been their setting, but it was the tradecraft that symbolized their characters’ plight and struggle. For Alicia Florrick, that would be the moral relativism of law.

These shows and their heroes agonized over what was right and what was wrong – prime time’s enduring struggle of good versus evil. Right versus wrong? Viewers knew the difference. Don Draper, Walter White and even Alicia Florrick didn’t necessarily. That’s what made them “conflicted,” flawed and fascinating.

Comparisons end there. “The Good Wife,” the creation of married showrunners Michelle and Robert King, was unique. It arrived in the wake of a series of high-profile sex scandals, most notably the 2008 prostitution scandal that destroyed former New York Gov. Eliot Spitzer’s political career. But the Kings were intrigued by the victim, not the malefactor: the spouse, who silently stood by as both supporter and prop. “We … thought there was no more interesting character in modern politics,” Robert King told the Los Angeles Times at launch.

Viewers first saw Alicia stand silently by as disgraced Illinois State’s Attorney Peter Florrick (Chris Noth) explained to the press that he did not use public funds in the patronage of prostitutes. While spinning this, Alicia noticed an errant loose thread on his suit sleeve, and reached for it.

A masterpiece of densely packed storytelling, “The Good Wife” also achieved a mastery of economy. These silent moments – a countless number over seven seasons – were so eloquent. We quickly learned Alicia chiefly occupied an interior world. What went on inside her head? We wanted to know. She wasn’t obliging, at first anyway.

In the early seasons, the show essentially pivoted between law firm Lockhart & Gardner – in the sharply drawn foreground – and Alicia’s interior life deep in the background. They almost existed in two separate realms, even though there would be a cosmic wormhole (so to speak) connecting them. In the ensuing scandal, and also during Peter’s later time behind bars, work for her became both salvation and validation, as well as a personal quest. In those offices, across those mahogany tables, she would learn who she was, or wanted to be, and also what was hidden in her heart. Will Gardner (Josh Charles) would help with that part.

Meanwhile, her teen children, Grace (Makenzie Vega) and Zach (Graham Phillips), were both reality check and anchor. “The Good Wife” was also (in a very real sense) “The Good Mother.”

Margulies was perfect in the role. Her face didn’t contort to reflect that inner struggle, but you could almost see her eyes turn inward to study her own thoughts and emotions. Alicia Florrick was watchful, but she watched herself as much as others.

That the practice of law on “The Good Wife” should involve the constant – and treacherous – navigation between right and wrong (often erring on the side of wrong) would have hardly come as a surprise to Alicia. Top in her class at Georgetown, a standout at another firm (where she would end up marrying the boss, Peter), she knew the game. What surprised her was just how good she was at playing it.

Also, just how ruthless she would become, too. At the end of the fourth season, she made a call to an unknown person. Come over now, she said over her cell. The audience (or at least I) fell for the assumption that she was about to surrender to her heart, and Will, once again. They expected to see Will standing there when the doorbell rang.

Instead, the knock came. The door opened. Her colleague and “fourth-year associate” Cary Agos (Matt Czuchry) stood there instead. She was going to join his new law firm and take Lockhart & Gardner’s biggest clients with her. Will didn’t know it yet, but he had a knife to remove from his back.

To understand Alicia’s evolution, and to appreciate it, you needed to appreciate all the other female characters who surrounded her. The transcendent actresses in those roles made that part easy. Christine Baranski’s Diane Lockhart was mentor and role model, also (perhaps) Alicia’s future foretold. Kalinda Sharma (Archie Panjabi) taught Alicia that the art of law was really just the art of war; leave no survivors behind. Elsbeth Tascioni (Carrie Preston) was comic relief, but also highly skilled and principled. Alicia discovered that Elsbeth’s feigned madness was her method. From the early seasons, Patti Nyholm (Martha Plimpton) taught Alicia that you could be a lawyer and mother at the same time, if you were willing to lug your babies to depositions.

The journey of Alicia ends Sunday, but where? How? Don Draper ended up on top of a cliff, dreaming up a famous Coke ad. Walter White lay dying after a gunbattle. Character defined their end. Character will define Alicia’s. Imperfect to the end and flawed – if not fatally – she was a good wife, good mother and good lawyer.

A good human being, too. She deserves a good end. Let’s hope she gets one.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.