Team sports may dominate the high school landscape in Maine, but there are also teenagers from every corner of the state following their own paths to athletic success.

Non-traditional, or niche, sports provide an alternative for some teenagers who have a passion for activities that fall outside the traditional lines of a high school field or gymnasium. In many cases, they spend countless hours training for competitions that rarely get attention. Few outside their close circle of family or friends know of their triumphs.

If there is one trait these athletes seem to share, it’s an independent streak that allows them to adhere to rigorous training regimens without the support of classmates.

Take Cassandra Albano, a 17-year-old synchronized skater from South Portland. She makes twice-weekly trips to Boston to practice with teammates, plus many more hours a week on her own at local rinks. Her classmates at Maine Coast Waldorf School are likely to never see her compete.

Albano admits there are times she wishes her accomplishments – making a select team and competing in regional competitions – would draw more recognition from peers. But not to the point where she’s ready to trade her skates for soccer cleats or running shoes.

“I’m not just one of the millions of people who play the same school sport,” Albano said. “It’s something unique. It’s very nice to have a different sport.”

Non-traditional sports are often born from common activities. Riding a snowmobile isn’t particularly unique, but how many people race them at speeds well over 60 miles an hour like Ben Humphrey of Pownal?

More and more New Englanders give surfing in the cold Atlantic a try. But few can rip a turn on an 8-foot wave like Maddie Ryan of Arundel.

So what type of person turns a weekend diversion into an all-consuming way of life?

“I think all of the standard cliche terms really do apply,” said Walt Shepard, a former world-class biathlete from Yarmouth. “Hard work, dedication, perseverance. I don’t use those terms lightly. Obviously they get thrown around a lot when talking about elite athletes. But for me and the guys I was competing against, we were literally the type of kids that after a workout, we’d be checking our heart rates at 12 years old.”

INTRODUCTION PHASE

Humphrey’s interest was sparked as a child by a neighbor who raced snowmobiles. Similarly, Isaac Douglass of North Berwick had a neighbor who had run obstacle course races and kept urging him to try it. Ryan grew up in a surfing family. Cody Johnson of Fort Kent attended a World Cup biathlon in his hometown and was immediately wowed.

Kevin Grondin, a six-time U.S. amateur surf champion and former U.S. team coach, is a mentor to Ryan. He agrees some form of exposure to a niche sport is needed. Then it’s up to the athlete.

“I think it takes a background of where you’ve been brought up and what you’ve seen to flavor your life toward surfing,” Grondin said. “However, to get to the level (Ryan is), that takes a special inner push.”

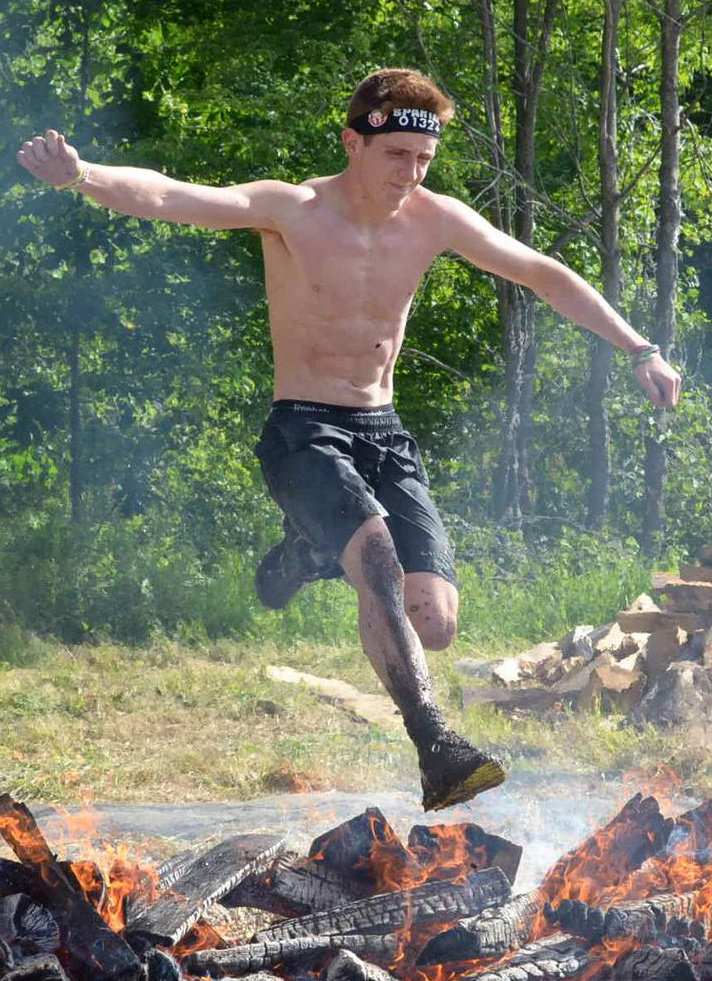

The ability to stick with it usually comes down to one key element, said Douglass, 18, a recent Noble High graduate. His training for long-distance obstacle races requires several hours of cross-training per day and, for a teenager, unusual attention to diet and nutrition.

It’s a grueling, sometimes painful process that leads to a race that takes – if he’s doing well – four hours to finish.

Why go through the struggle?

“Because I love it,” Douglass said. “I’ve come to love just being athletic and being able to train. I feel training helps me discipline everything else in my life, and if it wasn’t for that I don’t know what I would wake up for in the mornings.”

‘LIKE DOING IT MYSELF’

Douglass and Humphrey, 18, also played school sports.

Humphrey played soccer, a year of football and four years of baseball at Freeport High. He especially enjoyed being part of Freeport’s baseball team that made a surprise run to this spring’s Class B state final. But racing snowmobiles really gets him revved up.

“I guess it’s kind of fun having a team at some point and enjoying it with everyone. But I’m not really a fan of depending on other people,” Humphrey said. “I just like doing it myself so I know, whether it’s right or wrong, it’s all on me.”

Max Cobb, president and CEO of New Gloucester-based U.S. Biathlon, has seen his share of athletes cope with the loneliness of an individual sport.

“A lot of athletes draw support from a team setting,” Cobb said. “For a biathlete, when you have to go out and do those super long workouts, that takes a great deal of independence and just plain toughness. I think there’s a streak of – a character trait – of independence of all the athletes who succeed at that junior level.”

Bill Gayton, a psychology professor at the University of Southern Maine, has studied the mental aspects of sport for decades as a researcher, and in private practice.

“If you talk about motivation being intrinsic or extrinsic, certainly the intrinsic motivation is higher for the individual athlete,” Gayton said. “Being good is hard work. And it’s harder if you don’t have anyone there to either commiserate with or to kick you in the butt.”

TRAVEL CHALLENGES

Ryan, the surfer from Arundel, has competed up and down the East Coast, in Puerto Rico, and in June went to Southern California for a 20-and-under contest. Spartan racer Douglass has tested his endurance at races in Massachusetts and Vermont, and in July will crawl under barbed wire and over walls in Quebec.

Without a school shouldering the travel arrangements, and making the training and competition schedule, a good portion of the logistical and financial commitment falls on the parents.

“They do everything for me,” Douglass said of his parents, Heather and Walter “Ruddy” Douglass. “They make sure that I’m able to train, that I’m able to eat well and that I’m able to get to these races. If it wasn’t for them I wouldn’t be able to do it. They allow me to train, eat and sleep.”

Johnson, 19, was a member of the U.S. biathlon team that competed in the Youth World Junior Championships in Romania in February. He said he was 10 when he made the decision to try to become an Olympic biathlete.

Not long after he began training seriously, a coach gave him some life advice.

“He told me, ‘You can take two aspects of your life to be good at and there’s three aspects: Your sport, your work or school, and your social life. Choose two of them,'” Johnson said.

Johnson was home schooled to make training easier to fit into the day and earned his GED when he was 16. He said he began to “go out a little more” with friends when he was around 17, “but then I realized it was taking away from my training.”

Shepard, 33, agrees that dedication to a sport can take a toll on a social life.

“I can remember when I was 12 and actively saying no to my friends that wanted to hang out because I wanted to get my rest so I could train the next day,” Shepard said. “They thought I was pretty lame but luckily they stuck with me.”

IS IT WORTH IT TO BE DIFFERENT?

Johnson, 19, points out that he’s competed in Sweden, Romania and Alaska.

“I have friends from every corner of the country,” he says.

Douglass says training, in some form, will become his life’s work.

Then there’s the harder-to-define value of simply knowing you possess skills and experiences that separate you from your peers.

“I think there’s lots of value in that,” said Grondin, the surfing coach. “It allows people a little more peace in their own psychological frame of mind.”

Shepard went on to compete in three world junior championships and the 2005 world championships. He narrowly missed qualifying for the U.S. Olympic team in 2006 and 2010, and retired from competition six years ago.

“I would not change anything,” Shepard said. “I know it sounds a little corny but in life it really has to be about the journey more than the end state. I’ve had an amazing life experience.”

And what will Shepard do if his now 2-year-old son someday tells his dad that he wants to be a biathlete, or race snowmobiles, or be a synchronized ice skater?

“I wouldn’t stand in his way,” Shepard said. “I feel like the non-traditional path I started down when I was 12 years old and kept going down through different stages in my life showed me a different side of life.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.