“American Optimism” is a loaded title, a coin-flip between cynicism and Pollyanna jingoism. There are passionate perspectives from either side, particularly during an election year.

But Able Baker Contemporary’s foray under that title is merely a conversation starter for a challenging show of contemporary art. And it works. The topic is just enough context, but not too much.

If you feel the need to stitch the art to the theme, you mostly can; and when you can’t, you find yourself unpacking worthy works.

Chronologically, “Optimism” begins with prints by Grant Wood and Andy Warhol. Wood’s 1939 lithograph “In the Spring” shows a hardworking farmer, shovel in hand, looking up at the viewer (who has the perspective of a snapshot photographer) with a momentary smile of pride: He has already hand-dug an impressive line of tree-trunk fence posts. His farm is expanding. Things are going well.

Warhol’s culture of capitalism-fueled content can be seen as unbridled futuristic exuberance or as a razor-sharp takedown of American consumerism. However, Warhol’s signed poster for Werner Fassbinder’s 1982 final film “Querelle,” based on the 1947 Jean Genet novel that reads like Cain and Abel in a Sodom-based sailors’ opium-den brothel, is a gritty back door into imported consumer culture. Billy Budd it ain’t.

The other Warhol work in this show is triumphant proof he won the culture war. It is a Campbell’s soup can dress produced by the company after Warhol’s design. That’s right: A mass-production soup company made paper dresses designed by Andy Warhol. It’s brilliant and hilarious in about a thousand ways, and as a print, it’s a phenomenal thing.

While the print can hardly be seen as optimistic, it is American both in terms of consumer culture capitalism and art. (Pop Art was actually born in England, but the decidedly less cynical American brand came to dominate.)

The historical works are outliers in “Optimism,” but they form intersecting sides of a hard-edged frame for the rest of the show.

Between the Warhols, Adam Eddy’s “Self Portrait Cocktail Face” sits silly and stupefied on the floor as though in a floating pool lounge chair. Eddy’s game of laughing at himself is an effective ward against cynicism. His “Not a Life Saving Device” is a wittier-than-usual object piled on the endless column of art, echoing Rene Magritte’s “This is not a pipe” (it’s not a pipe, but a painting of a pipe – a representation), but it dries out the celebratory intoxication of the self-portrait just a bit.

Whatever the goals, “Optimism” is a show defined by very strong New York-flavored contemporary painting. Heidi Hahn’s “Everyone We Know Is Already Here 2” is like a hipster model: tat-covered and pierced but somehow gorgeous nonetheless. The narrative immediately dead-ends where a creepy Munch-meets-Gottlieb figure and pink-outfitted, blobular dog stand before a trailer-like home. What is most notable, however, is the paint. Often it swirls deliriously, sometimes it lushly layers to showcase its translucent abilities, and elsewhere it gathers like generously spread butter.

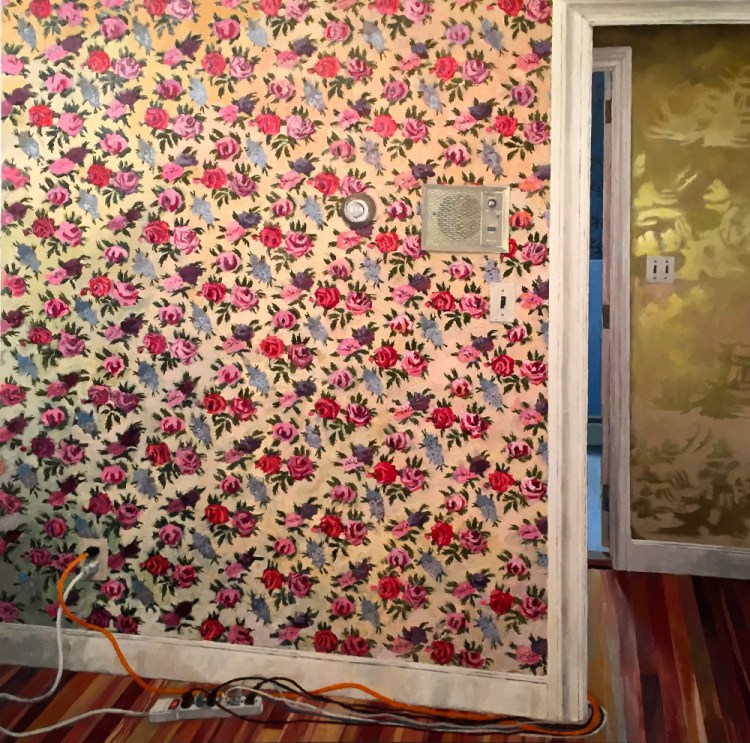

Jarid del Deo’s “Set the Controls for the Heart of the Sun” is more straightforward in painterly terms: A view of a rather disregarded wallpapered wall, around which an octopus of power cords snakes into another room, where we suspect the real action is happening. Is it plot-worthy action, or an unkempt guy gaming in his mom’s basement? It’s up to the viewer. Whichever way, del Deo sympathetically blends the mental intensity with the casual setting.

Del Deo’s literalist Market Basket flier painting is more of an inside joke for painting fans. It’s nicely painted and timely (the Market Basket in Biddeford rocks), but it doesn’t reach similar works, like those by Richard Estes, well enough to comment on them; and the trick is that the painting feels accurate now, but it won’t at some point.

Mark Gibson’s “These Guys Take Heads” has that recognizably Brooklynesque uber-hip flat paint and insufficient narrative sense. We see a purse, a leather satchel and a plastic shopping bag jammed together. If the thing on top is a bedroll, the context is homelessness, and the question of what such a person is doing with a wolf mask with pink-edged fangs gets a bit unnerving. It’s not a pet, since that bag is plastic. An actual head? Not likely. As a painting, it intrigues with a dark spark.

David Humphrey’s “Air Processing” rather literally reads like a textbook on how to make a hipster contemporary painting. An abstract painting is leaned up against a window behind a heating/AC wall unit with the controls exposed and a cartoonish stuffed animal perched upon it. The whole scene swims in swimming pool green, that retro beacon. But Humphrey can paint, and both his scene and his pictured abstract painting succeed.

The trick here is that the abstract painting can be seen as a representation of an abstract painting or a literal abstract painting. It’s hardly new, but like any nifty sleight of hand, if it works, it works.

The accomplishment of Philip Brou’s two high-focus portraits warrants particular acknowledgment. There is a backstory to why Brou paints movie extras in extraordinary detail, but I preferred my initial, direct experience of them. The models are average people painted with such precision that the artist’s dedication to painting and its most painstaking processes comes across like absolute faith. It’s impressive and pleasantly respectful.

The fabric of the sitter’s shirt in “The Warriors” (Brou’s life-sized paintings are named for films in which the extra appeared) is what puts Brou into rare company – not his pop-culture process. However, that process pops because of the curatorial decision to hang this work next to Katherine Bradford’s whipped-off-in-five-minutes “Superman Responds,” a simple scene of the ever-recognizable caped figure flying on a white ground with blue and red edges (jingoism and an alien – oh no!). Next to the Brou, this work awakens ideas about dreams, reality and legibility. Those extras, after all, actually appear in movies. And isn’t that one of the most common American dreams?

Several excellent galleries in Portland have closed in recent years, or in the case of Susan Maasch Fine Arts, will close soon. New and unknown venues can’t replace the ones we know and value. Still, Able Baker is brand new, and what I see there gives me cause for optimism.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.