In “Cold Blood, Hot Sea,” Charlene D’Avanzo’s first mystery novel, Mara Tusconi is a scientist with the Maine Oceanographic Institution. Headquartered in Spruce Harbor, Maine, the institution is an international leader in climate change research. Tusconi’s particular field of study is climate change’s effect on ocean temperatures.

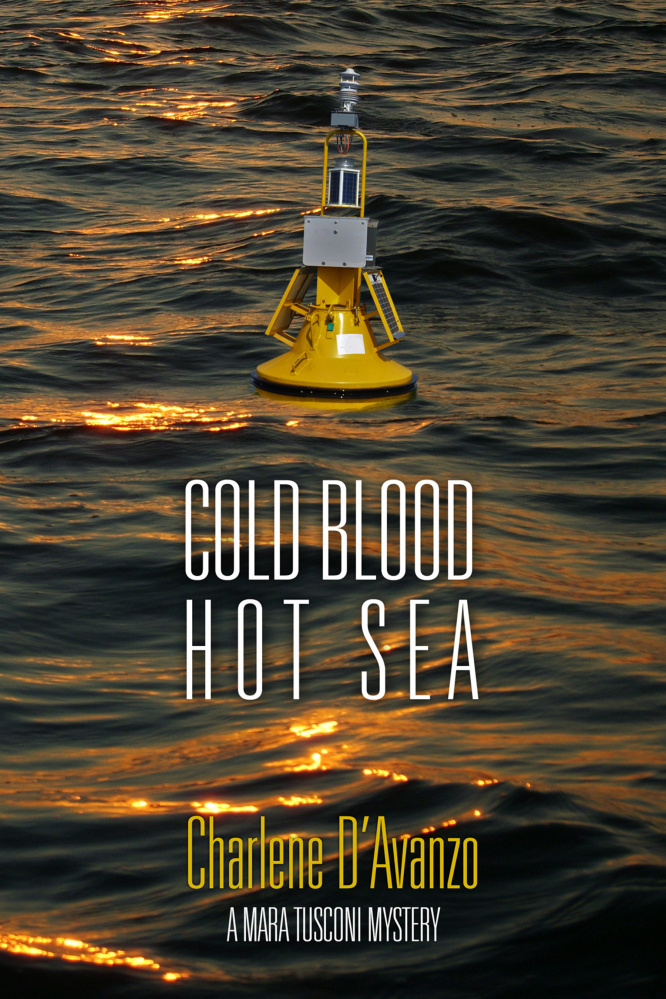

As the book begins, she’s taking off on a research cruise to record April temperature gradients in the Gulf of Maine. The trip turns deadly when one of her colleagues is crushed by a heavy buoy. Was it just an accident? Were all the people on the boat at the time – scientists, crew and an unexpected passenger – actually on board for the right reason?

The answer involves an increasingly dangerous group of climate change deniers, a mystery email suggesting that fraudulent science is being practiced somewhere close to home, a sinister multinational oil company, and young Tusconi’s initiation into the rough world of sleuthing. (This is the first of a projected series of Mara Tusconi Mysteries.)

D’Avanzo herself is a marine ecologist who has studied the New England coast for 40 years.

So it’s a fair bet that when it comes to research vessels, labs and scientific protocols, she knows her stuff. In addition to the research background, she packs in a lot of facts and figures about global climate change.

Welcome to cli-fi, a new literary genre. Publisher Torrey House Press, according to its website, is dedicated to the belief that “culture is changed through conversation and that lively contemporary literature is the cutting edge of social change.” And its goal is to “develop literary resources for the conservation movement, educating and entertaining readers, inspiring action.”

Lively contemporary literature notwithstanding, it’s really not possible to apply the usual benchmarks of good storytelling – character development, pacing, realistic dialogue – to books like “Cold Blood, Hot Sea.” Using a mystery story as the vehicle for a dissertation on climate change is like trying to mix oil and water.

The science is simply too voluminous to be integrated into the narration’s forward motion without bogging it down. In an effort, presumably, to make this expository lemon into lemonade, the author has Tusconi coached in making climate science accessible to the public. “Scientists speak in code,” her instructor tells her. “When you talk to the press, you must use plain language.” Problem solved? Not really.

Considering these straitening factors, however, D’Avanzo does a fairly good job of crafting her story. At least she is confident enough to allow her protagonist to say to her friend, without obvious irony, at one point, “Damn, Harv. You make this sound like a cross between a soap opera and a cheap mystery novel.”

She introduces us to a handful of mostly believable men and women, whose characters are filled out in various subplots. Motive and rationale for turns of plot are sometimes a bit of a stretch, but the action scenes are genuinely thrilling page-turners.

Statutory red herrings – required to keep the mystery fan guessing – are nicely handled. And as a bonus, there is an enormous lobster called Homer (Homarus americanus being its scientific name).

The problem, as the master of it, British humorist P.G. Wodehouse, once said, is with “what we authors call dialogue.” It’s tricky enough to master the skill of making human interactions sound natural instead of stilted. When you have to also include a lot of exposition about climate change or ocean acidification, it is well-nigh impossible. For instance:

“What did you think about that paper I sent you about acidification and oyster larvae?”

“Well, it’s the first credible study that shows larvae might be able to adapt to low pH and grow normal shells.”

The Down East setting is, of course, a plus for Maine readers who will find most of the scenery recognizable, even if they won’t find the places in the DeLorme Atlas & Gazetteer.

There are curious inconsistencies, though. The Portland newspaper is the Ledger, but mention is also made of the Kennebec Journal, the Augusta paper’s real name. MITA – the very real Maine Island Trail Association – gets a shout-out. “Sign up when you get home, or I’ll come after you,” Mara tells the man she has her eye on.

All in all, Mara Tusconi is an attractive enough character, dealing compellingly with issues I care about, that I wouldn’t mind encountering her again.

But I can’t help questioning the publisher’s apparent assumption that any climate change-denying mystery aficionados picking up this book will become eco-converts as a result.

Thomas Urquhart is a former director of Maine Audubon and the author of “For the Beauty of the Earth.”

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.