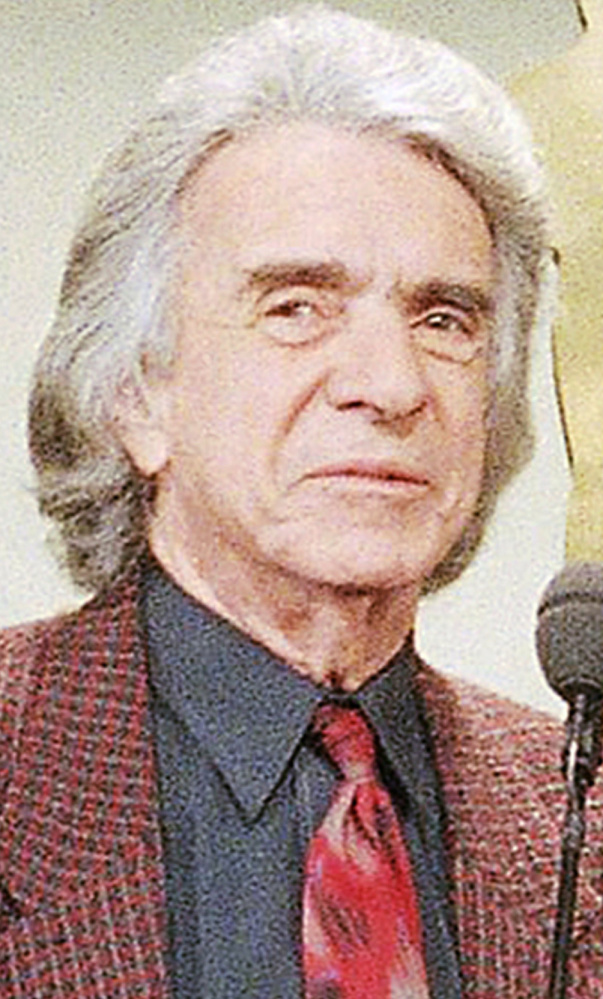

LOS ANGELES — Arthur Hiller, the Canadian-born director who emerged from the days of live television in the 1950s to become a filmmaker best known for comedies such as “The In-Laws” and “Silver Streak” and a romantic tearjerker, the 1970 blockbuster “Love Story,” has died. He was 92.

Hiller died Wednesday of natural causes in Los Angeles of natural causes. His death was announced by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Hiller was president of the academy from 1993 to 1997. He also served as president of the Directors Guild of America from 1989 to 1993.

In a more than 50-year directing career that was launched in radio and television in Canada, Hiller made his feature film debut with the 1957 drama “The Careless Years,” two years after arriving in the United States.

His credits include the war movie “Tobruk,” the horror movie “Nightwing,” the musical “Man of La Mancha,” the biographical film “W.C. Fields and Me” and dramas such as “Miracle of the White Stallions” and “The Man in the Glass Booth.”

But the bulk of Hiller’s more than 30 films were comedies and comedy-dramas, including “The Americanization of Emily,” “The Out of Towners,” “The Hospital,” “Plaza Suite,” “See No Evil, Hear No Evil,” “Author! Author!” “The Lonely Guy” and “Outrageous Fortune.”

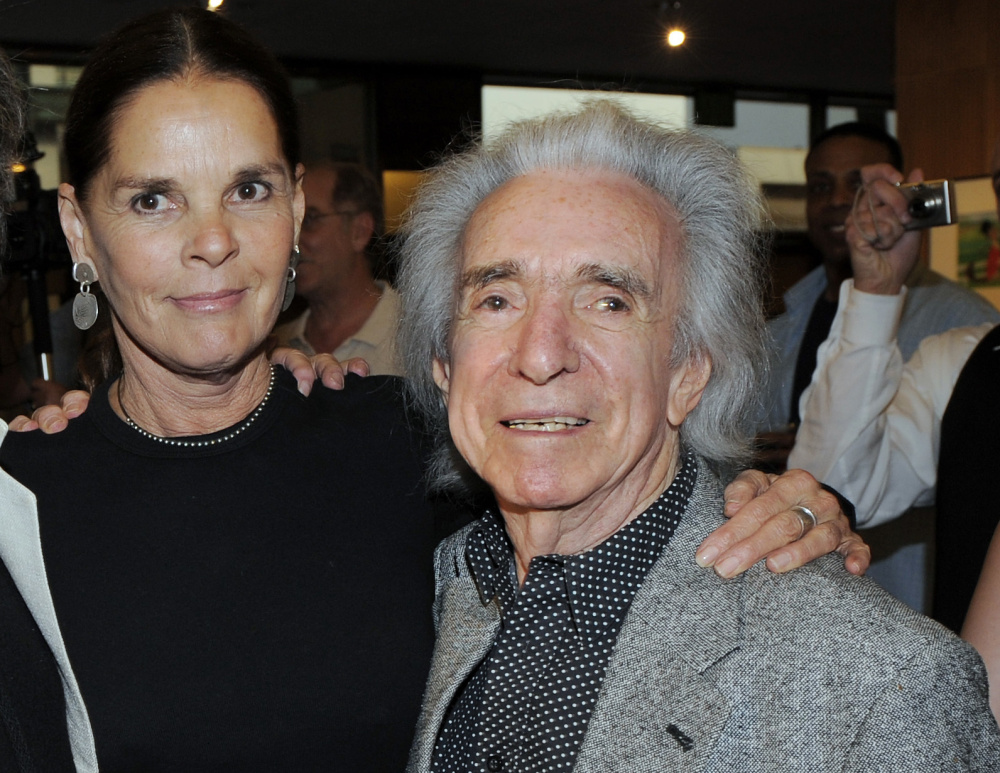

Hiller won a Golden Globe and received his only Academy Award nomination for “Love Story,” starring Ryan O’Neal as a super-rich, hockey-playing Harvard student and Ali MacGraw as a high-spirited working-class Radcliffe student who utters the immortal line, “Love means never having to say you’re sorry.”

When Paramount sent Hiller the script written by Erich Segal, he reportedly read several pages before letting loose a big “Yeccch.”

“I thought, they’ve got to be kidding: A story about a rich boy and a poor girl?” Hiller told the Los Angeles Times in 1971. “But when I finished reading it, I had a tear in my eye. … What made me do it was that the film is an affirmation of the human spirit.”

Paramount at the time was “in rocky financial shape,” Hiller recalled in a 1991 interview with The Times. “Bob Evans, who was running the studio then, loved the project. And he said we could make it if I would swear – and I literally had to swear – that I would bring it in for under $2 million.”

“I thought I was just making a nice little movie,” Hiller told Canada’s Globe and Mail in 2002.

“When we were putting it together,” he recalled, “we thought, ‘Gee, we could do with a couple of little scenes,’ so I went to Paramount and I said, ‘I want to go back (to Boston). I had come in $25,000 under budget, and finally they let me have $15,000.

“With a small crew, we returned to Boston and bumped into the worst snowstorm in 20 years. So I made up that whole scene in the snow” in which the film’s two young lovers playfully romp in the snow immediately after a low-key scene in which MacGraw’s Jennifer Cavalleri tells O’Neal’s Oliver Barrett IV that she loves him.

“The picture wouldn’t be the same without it,” said Hiller. “I could have said, ‘Oh, it’s snowing,’ and listened to the producer who said, ‘We’ll call it a day and wait until tomorrow,’ but everyone got into it, you know, the hand-held camera just watching them play …”

“Love Story” received seven Academy Award nominations, including one for best picture, and it won an Oscar for Francis Lai for original score.

Hiller had taken a reduced salary in exchange for percentage points in the film, which broke box-office records. And, as he told the Ottawa Citizen in 2004, “It worked out very well for me financially.”

The gentle-mannered, slightly built Hiller boasted a mane of gray hair that one newspaper writer deemed “worthy of Beethoven.” In addition to serving as the motion picture academy’s president, he also was a member of its board of governors.

In 1999, he received the Robert B. Aldrich Award for “extraordinary service to the Directors Guild of America and to its membership.”

Hiller was born Nov. 22, 1923, in Edmonton, Alberta, where his parents launched a Yiddish theater. By age 7 or 8, he later recalled, he was helping build and paint sets and at 11 was donning a fake beard to play small roles.

His interest in theater continued in high school, where one of his friends was future actor Leslie Nielsen. But Hiller reportedly turned down a drama scholarship at Ohio State University “because drama was what you did on weekends, not what you did for a living.”

He was a student at the University of Alberta in 1941 when he left to volunteer for the Royal Canadian Air Force and served as a navigator on bombing raids over Germany.

After the war, he earned a bachelor’s degree from the University of Toronto in 1947, followed by a master’s degree in psychology in 1950.

Despite never considering theater a profession, he said in a 2002 interview with Canada’s Times Colonist, he realized, “I’m not doing what I really love to do.”

So he went to the headquarters of the Canadian Broadcasting Corp. and asked the receptionist, “Who do I see about a job?”

He had thought about an acting or announcing job, but when the receptionist asked what kind of job, he found himself saying he wanted to be a director.

“To this day, I don’t know what prompted that,” he recalled. “But three weeks later, I was directing a public affairs broadcast.”

He directed everything from radio dramas to musical programs before moving on as a director with CBC television. In 1955, NBC offered him a directing job on one of its live TV anthology series.

He went on to direct episodes of series such as “Matinee Theatre,” “Playhouse 90,” “Zane Grey Theater,” “Alfred Hitchcock Presents,” “Gunsmoke,” “Route 66,” “Ben Casey” and “Naked City” (an episode of the last earned him an Emmy nomination in 1962).

Hiller had his share of misses at the box-office, including the critically lambasted box-office failure “An Alan Smithee Film: Burn Hollywood Burn,” a documentary-style 1997 satire written by Joe Eszterhas and featuring numerous celebrity cameos.

Alan Smithee was the official Directors Guild of America-sanctioned pseudonym given when directors, typically displeased with a film’s final cut, requested their name be removed from the credits.

Ironically, Hiller opted for an Alan Smithee credit himself after Eszterhas reportedly edited Hiller’s cut of the film.

“This is no stunt, this is very painful for me,” Hiller told Daily Variety in 1997. It was Cinergi Pictures Entertainment’s decision, he said, “and clearly they decided to release Joe’s version, which was radically different from my own.”

(The use of the Alan Smithee pseudonym later fell out of favor because it had become so well known.)

Over the years, Hiller supported and worked with various organizations, including the Motion Picture & Television Fund, Amnesty International, the Deaf Arts Council, the Anti-Defamation League and the Venice Family Clinic.

In 2002, he received the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

“It’s so embarrassing to receive an award for doing what you should be doing,” Hiller said in his acceptance speech.

Hiller is survived by his daughter, Erica Hiller Carpenter, his son, Henryk, and five grandchildren.

Gwen Hiller, his wife of 68 years, passed away in June.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.