Maine plays an important role in American art history, which means people from outside of Maine have perspective on the state’s role in the American art landscape. But Maine’s role in art history has been almost at odds with its ongoing place in that landscape: Leading artists came to work in peace and privacy in Maine, then left with their made-in-Maine works to sell in larger markets like New York.

While visiting South Korea recently to give a talk about glass art, I gained some new perspective myself on just how Maine art is perceived from afar.

In Seoul, I was shown a book by the renowned Korean photographer, Woong Chul An, that includes a chapter about Portland. An is known for his portraits of leading artists, such as Jeff Koons and Francesco Clemente, but particularly for his intimate images of important musicians, including Herbie Hancock, Bobby Mcferrin and the famously camera-shy Keith Jarrett. An’s book “Still Life” includes chapters about photogenic, storied and art-hefty places around the world. His chapter on Portland, however, is quite different.

In it, he recounts the story of going to Maine to photograph the Korean-born painter Jung Hur, a friend of mine, in his Portland studio. But Hur had many other obligations and so An, who speaks little English, was largely left to wander Portland on his own. An’s visit was during the snowy winter of 2010. He had never seen so much snow, but he braved the cold with camera in hand. In his book, An wrote that Maine was an unlikely place for a Korean tourist to find himself. (We can hope this is changing now that Maine’s lobster industry is so connected to Korea and, perhaps more importantly, Park Bom, a Gould Academy graduate, of the group 2NE1 is one of K-Pop’s leading international superstars.) But he was surprised by the depth of Portland’s art scene, the many art venues and the urgent energy of the city’s artists and galleries.

An’s images of Maine are primarily landscapes: an isolated ice fishing shack on a snow-blanketed lake, a richly textured deep red brick wall of an old Portland building, or the tip of a tall tree seen over a snow-covered berm reaching two-thirds of the way up the image. This last one is a witty play on the extreme depth of the snow: The hill plays the part of the piled up snow, reaching so high that it almost buries the tall tree.

One image, however, is not like the others, and the text reveals it marked a turning point in An’s attitude as well as his work. It is a polka dot-like scene (think Dalmatian) of many images of a Maine boy and his dog playing in the snow represented by the white ground of the photo paper. The dog is a black Pomeranian, so it looks like a bushy black brushstroke each time it’s shown. The boy is wearing a black coat and boots, and so he is only really revealed when you are close enough to recognize the blue of his jeans. As we look at the dozens of images of the boy and dog, we realize An isn’t just taking a photograph of a boy and his dog: He is there, interacting with them. And we, the viewers, join in as well.

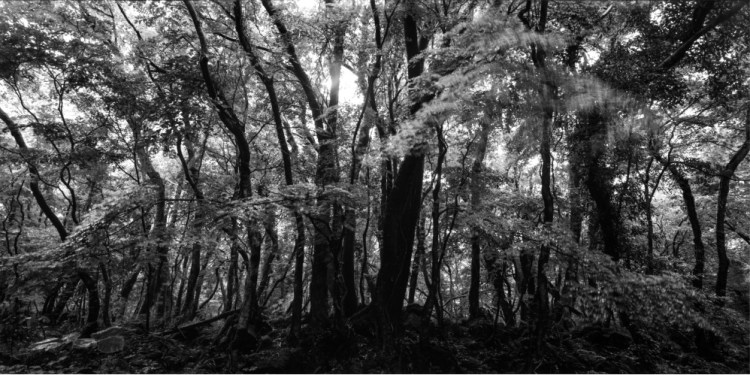

An’s newest work has a sense of the Maine landscape. This is not to say there is a direct relationship or influence, but since this body of landscapes came after his engagement with Maine, there’s no reason to deny it either. What resonates, however, is the similarity of the density and urgency of An’s images of the Gotjawal forest on Jeju Island, one of Korea’s nine provinces. Rather than the more common sense of picturesque, these images share qualities we see in the Maine landscapes of painters like Tom Hall, Lois Dodd, Richard Estes, Neil Welliver and others who followed the trail blazed by artists like Frederic Church, Winslow Homer and Marsden Hartley. This kind of landscape is not a pretty glimpse on a path, but a mystical sensation of special place. Whatever the source of the spirituality, it is a this-place-now approach that arouses our conservationist instincts. It is a sensibility long associated with New England through the American Transcendentalists, like Thoreau and Whitman.

Several of An’s Gotjawal images are now on view at L153, a small gallery in Seoul, but many more will be featured in a show opening in October at Column, a cavernous, quirky space. Unfortunately, Gotjawal is endangered by growing tourist development on Jeju, so An’s urgency – a quality less apparent in his other work – is not simply an effect of visual theater.

As I headed to Korea, I had wondered about whether art communities there had any sense of Maine as a center for visual art. After all, Seoul had a huge statue – “The Hammering Man” – by Ogunquit artist Jonathan Borofsky long before his Maine debut at the Center for Maine Contemporary Art’s new building this past summer. And I had been surprised to find the glass art faculty at Namseoul Univerity was aware of Maine because they had worked with glass artists like Ben Cobb, who hailed from Maine. We have several leading painters in Maine, including Catherine Breer and Jung Hur, who grew up in Korea, but that doesn’t mean they are associated with Maine, as opposed to America in general.

More than any specific insights, however, I was left with the idea that our art communities should consider what Maine as a center for arts looks like to the outside world. Is Maine seen primarily as place for artists to work? Is it a place of venues worthy for art enthusiasts to visit? Is the Maine art scene perceived as one that is growing and expanding? Or is it primarily a place of history, where giants once walked?

Personally, I hope An’s (accurate) perception of an unexpectedly rich arts scene is what the world sees. Maine has always had the artists, and now that the Maine College of Art students are not automatically leaving Portland when they graduate, the city is thicker than ever with emerging talent.

The question I have is an important one right now, as the art scene in Maine is experiencing some dramatic shifts: How do we want to be seen by the rest of the world?

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.