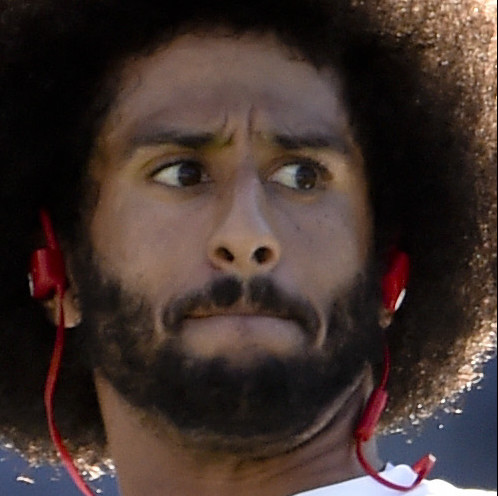

When Colin Kaepernick kneels, you know where everybody else stands. Kaepernick’s refusal to brace at attention for the national anthem has provoked a variety of sharply defined responses, from Megan Rapinoe’s sympathetic bended knee to Bill Lynch’s accusations of hijacking. But curiously, Kaepernick himself remains vague. In fact, when you think about it, those who have replied to Kaepernick have said more interesting things than the man himself.

With the NFL opening its season this week, Kaepernick again will kneel, and no doubt others will too.

But anyone trying to figure out whether to be offended by or congratulatory of Kaepernick runs straight into that vagueness, the amorphousness of his gesture. Let’s face it: He’s not the most clarion of dissidents. Tommie Smith and John Carlos had a list of human rights demands along with their raised gloves in Mexico City in 1968: They wanted apartheid nations thrown out of the Olympics, Muhammad Ali’s boxing title restored, and more African American coaches. But Kaepernick’s protest has no such specific aim. He has offered only a generalized explanation that he doesn’t want to salute a nation “that oppresses black people and people of color,” followed by a soft clarification that he doesn’t mean to slight the military or police.

He has made large pledges of money to non-specific causes: He will give $1 million to “different organizations.” But he hasn’t said which or why. On Instagram he thanked “the people” for making his jersey the top seller, and said he will donate “all the proceeds I receive … back into the communities.” But doesn’t say where or for what.

It’s the very broadness of Kaepernick’s protest, in fact, that has stirred so many rebounding opinions. He’s not a shoulder-to-the-wheel activist like DeRay McKesson of Black Lives Matter, who ran for mayor of Baltimore. Rather Kaepernick seems to be a practitioner of what New York University professor of media studies Stephen Duncombe defines as “Ethical Spectacle,” the strategic use of a symbol, sign or gesture to seek a cultural shift.

Kaepernick’s kneel during the “Star-Spangled Banner” may be vague, but it’s powerful in its mute symbolism – more powerful in fact than his platitudes. And make no mistake, he has risked something with it, in a league that promotes itself as a war game and brands itself with the flag. As Roger Goodell went out on a limb to say, the NFL “believes very strongly in patriotism.”

The main thing Kaepernick has accomplished is to inflame an engrossing debate and serve as a reminder that dissent is a form of patriotism too. If that was his goal, then he’s succeeded wonderfully. You may have learned more in the last week about Francis Scott Key’s slaveholding and the battle of Fort McHenry than you would have otherwise. And you may have started thinking harder about the meaning of anthems. Anthems are supposed to express something of our national character, but they also sound uncomfortably aggressive in the hands of mobs and dictators. Isn’t coerced loyalty a contradiction in terms?

Kaepernick’s gesture has become a sort of prism, through which all kinds of public figures have debated and offered their own beliefs. Whatever you think of Kaepernick himself, you have to feel admiration for those who have spoken their thoughts so coherently – the Nate Boyers, Ben Watsons, Rapinoes and Lynches.

Here is Boyer, writing to Kaepernick in the Army Times: “I didn’t enlist to fight for what we already have here; I did it because I wanted to fight for what those people didn’t have there: Freedom … I’m not judging you for standing up for what you believe in. It’s your inalienable right. What you are doing takes a lot of courage, and I’d be lying if I said I knew what it was like to walk around in your shoes. I’ve never had to deal with prejudice because of the color of my skin, and for me to say I can relate to what you’ve gone through is as ignorant as someone who’s never been in a combat zone telling me they understand what it’s like to go to war.”

Here is Watson, tight end for the Baltimore Ravens and author of “Under Our Skin,” a book of ruminations on race, writing a splendid essay from the hospital after suffering a torn Achilles, on why he stands for the anthem.

“I stand, because this mixed bag of evil and good is MY home. And because it’s MY home my standing is a pledge to continue the fight against all injustice and preserve the greatest attributes of the country, including Colin Kaepernick’s right to kneel.”

On opposite ends are Rapinoe and Lynch. The soccer star has supported Kaepernick by kneeling during the anthem because she believes “We need to have a more thoughtful, two-sided conversation about racial issues in the country.” But Washington Spirit owner Lynch, an Air Force vet, obstructed Rapinoe’s display during a Seattle-Washington game Wednesday by having the anthem played before the teams took the field, and issued a thoughtful if provocative statement.

“While we respect every individual’s right to express themselves, and believe Ms. Rapinoe to be an amazing individual with a huge heart; we respectfully disagree with her method of hijacking our organizations’ event to draw attention to what is ultimately a personal – albeit worthy – cause.”

With all of this back and forth, Kaepernick, unwittingly or not, has gotten at something important, the inherent antagonism between what the country has been, and what it wants to be. Our national songs contain tradition and remembrance, yet also an undeniably awful racial history. As historians John Stauffer and Ben Soskis write in “The Battle Hymn of the Republic: A Biography of the Song That Marches On,” the very same historical events that “support a unifying national identity also threaten to stoke sectarian and sectional divides.” The Battle Hymn, for instance, with its origins in the Civil War, contains powerful internal contradictions between “unity and divisiveness.”

As Watson eloquently suggests, the same song that calls attention to national ideals also begs attention to the nation’s sins. The same song that promotes national interests and preserves tradition also highlights its failings.

If you’re upset or confused by Kaepernick, well, just remember that’s the consequence of being American. Frederick Douglass once said that being willing to expose those tensions is what makes real American reformers. “They see what ought to be by the reflection of what is,” he said, “and endeavor to remove the contradiction.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.