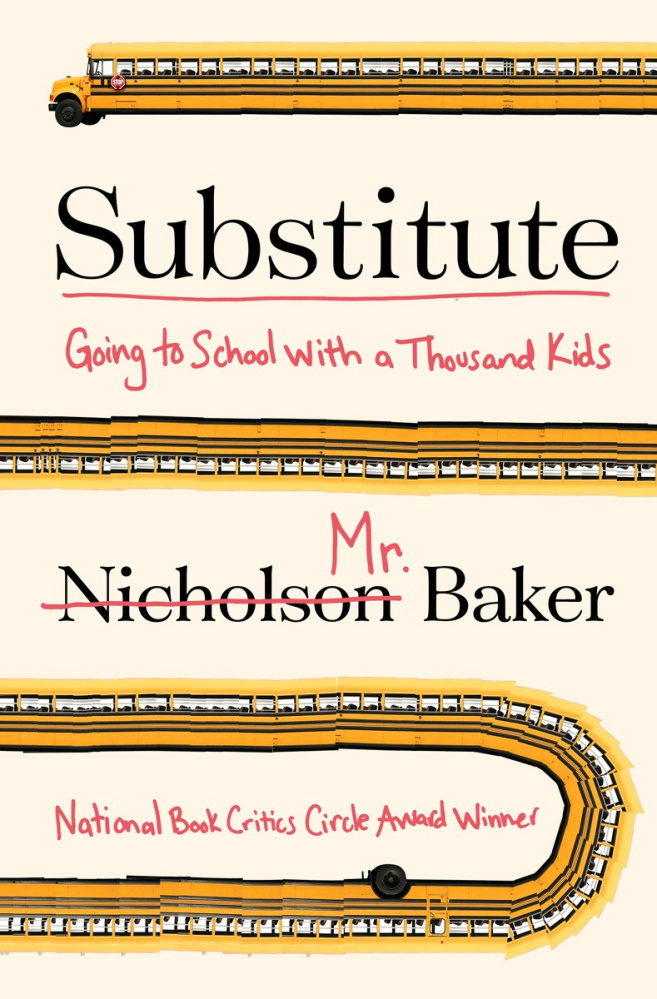

Nicholson Baker has written more than a dozen books on such varied topics as World War II, libraries and voyeurism. For his latest nonfiction book, “Substitute: Going to School With a Thousand Kids,” the acclaimed novelist and author sampled a career change.

In 2014, Baker signed up as a substitute teacher in the Maine public school system where he taught at every level, over a period of 28 days. Assessing the state of education after such a meager stint may appear presumptuous. Yet Baker documents the day-to-day cacophony of the classroom, and his role in it, with a level of detail that becomes mesmerizing. Not surprisingly, he favors higher pay for teachers and a shorter school day. But this is a book about people, not policy.

“I’m trying to open a window on a world that couldn’t be videotaped,” he says. “There is so much confusion and interruption and noise that the soundtrack would be unbearable. The only possible medium to show this rich jungly world is the printed word.”

Baker, whose own children attended Maine public schools, spoke recently from his home in South Berwick about language, homework and his fear of little kids. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: Reading your book, I got the sense that each day was its own kind of maelstrom.

A: The substitute teacher is the person on the lowest rung of the school ladder. Students try to break you. You don’t know what’s being taught; you have to figure it all out on the fly. If you want to get through the day, you have to pull from your background knowledge of life – the survival scraps, and the twigs and the branches that are right there. Each day was a different group, so each day was exhausting in a different way.

Q: I was impressed that the nearby teachers would check in on you, that they all seemed very kind and concerned.

A: Well, this is Maine! They sort of felt sorry for me. They would give me a heads-up that this group can be challenging. But that was the fun of it. When you’re in the midst of a mountain-climbing adventure, it’s very uncomfortable. But at the end, you’ve learned a lot and you’re glad you’ve done it. That’s what it felt like for me. I made it – I survived.

Q: We hear constantly about how needy and demanding kids are, but we hear little about how monotonous the teacher’s job can be.

A: It’s a kind of Groundhog Day experience in junior high and high school because you’re teaching the same thing, often four or five times a day. I found that I got slightly better at it over the day, but I also got slightly more exasperated with the material sometimes. Basically I just splashed through the marsh as well as I could to get to the end of the day.

Q: At the end of each section of the book, you were counting down each day. The kids are counting the minutes.

A: There’s a strange focus on the clock. Time is so important in a class. That feeling of everything being broken into little pieces and then doled out is one of the fascinating aspects of it.

We’re asking a lot of kids. Nobody knows how hard they’re working – even when they’re working to avoid work! It takes creativity to be a funny cut-up in class and not do the work. It takes energy. Every kid in school is exhausted at the end of the day.

Q: You describe one student who had 19 overdue assignments.

A: When I grew up, there was minimal homework. You couldn’t fall that far behind. Now it’s more like a very fast escalator and you can lose your footing quickly. Is it actually good for the mind to be doing this many assignments per day?

There is this belief that the mind is a muscle, and everything is like language. If you’re not exposed to it when you’re young, you will never learn it. The fact is, you learn a lot of things better, later in life, when you have a hunger for them.

Q: You had a great discussion with one class about their notion of the ideal school day. One of the girls basically said that school should start at noon and end at 12:01 p.m.

A: These kids are not stupid – they’re just not interested in learning the school’s narrow range of subjects. Some kids are brilliant at taking apart lawn mower engines, or they’re incredibly good at making stuff grow. There are all kinds of ways to be a kid. They just need to reach a certain minimum level of reading, they need to speak English and write some language. Beyond that, there are people who want to learn more, and read more and do more. You never want to get in the way of that.

Q: What was the high point of your teaching experience?

A: I had a fear of the younger kids. I thought that I wanted to teach high schoolers and maybe junior high schoolers. But it turns out that the little kids were really incredible. They have a lot to teach you. And there’s a generousness of spirit and a kindheartedness that comes out of them. Sometimes when things were out of control, one of the little kids would become my helper and give me little hints very discreetly: “You might want to think about getting us ready for recess now.”

It was a totally life-changing and life-improving experience for me in all ways.

Q: When you went into this project, did you imagine that it might be life-changing?

A: Well, I thought it would just give me a little more authority. I didn’t realize that you have to throw theory out the window and take what they have to teach you at that moment. Most of it is just raw life; it can’t be put in a textbook. I thought I would be able to bolster my opinions, but instead I’m humbler about the whole thing.

I met substitutes who were amazingly agile – good at figuring out what the teacher wanted and just making it happen. And some of the substitutes were people I really learned a lot from and admired. They didn’t necessarily have fancy resumes; they just had an instinct for people.

There are some who try being a substitute teacher and, after a day or two, say, “This is not for me.” That certainly crossed my mind several times. I really overestimated my own ability to tolerate chaos.

Q: How chaotic did it get?

A: I remember thinking at least once, “Is this the worst day of my life?”

Fifth grade turns out to be really rough. And I lost control of it. It was like flying a kite and the string slips from your hand. The principal had to come in; it was a mess. So I felt shamed and incompetent.

But what I valued most is the way kids use language. They’re trying to figure it all out, and they come up with beautiful phrasing.

Q: But they were also lucky, because you were the rare substitute who would love the way they phrased something.

A: As I started to write the book, I thought I would have more about the philosophy of education. As I got into it, I realized I wanted to talk about the way kids speak. Sometimes a kid says something that encapsulates a whole world of emotion that I wanted to convey. There was one kid who had sad eyes, and a blank piece of paper and he said, “I suck at everything.”

What are we going to do about a kid like that?

He and I could talk about anything, but instead, in the midst of this chaotic classroom, he was expected to do all this math and writing – and he couldn’t write, poor guy. He’s going to be fine. But he has been made miserable in a way that doesn’t need to happen.

Q: If you could give one piece of advice to a new substitute teacher, what would it be?

A: Any classroom is a fascinating microcosm of human behavior. You can see factions forming, and rifts and reconciliations. You could watch the whole history of the world happen in a single day, with 20 kids. I would just say, think of it as something you can’t control and try to enjoy it. When the kids laugh, laugh with them. Just ride the waves.

Joan Silverman writes op-eds, essays and book reviews. Her work has appeared in The Christian Science Monitor, Chicago Tribune and Dallas Morning News.

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.