ELM STREAM TOWNSHIP — There were no moose in sight during the drive up the west side of Moosehead Lake toward the hunting camp. No moose as the drive continued another 40 miles on unpaved roads into the heart of the North Maine Woods.

Here in Somerset County in northwestern Maine, finding a moose has become difficult – even for some of the most experienced hunting guides.

“It’s not like 30 years ago when there were clear-cuts. Then you could ride up and down the roads and see them,” said Jake Allain, a Registered Maine Guide.

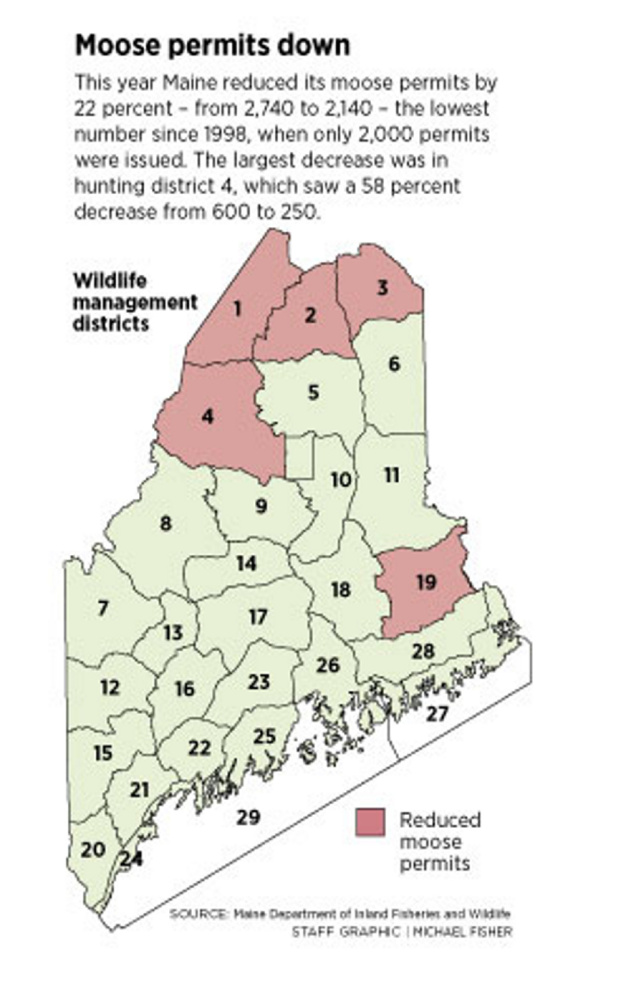

Last week marked the start of Maine’s annual moose hunt – with the fewest hunters in 18 years. The Department of Inland Fisheries & Wildlife reduced hunting permits by 22 percent this year to meet public demand for greater opportunities to see moose, particularly in northernmost Maine.

Wildlife Management District 4, where Allain has his hunting camp, has been hit the hardest. Permits were slashed from 600 to 250.

“I think there are less moose there,” said DIF&W moose biologist Lee Kantar, who took part in aerial surveys of the herd earlier this year. “When you look at District 4, that is a huge area, almost 2,000 square miles. I’d say after we flew this winter, the moose are probably having some impact from winter tick.”

Winter ticks are devastating moose populations in New England, Kantar said. In 2014 and 2015, DIF&W cut permits significantly over concerns about moose survival rates because of winter-tick infestation. The 2,140 permits allocated statewide in 2016 are nearly half those allotted three years earlier (4,085).

District 4 lies north of Mount Katahdin and runs along the Canadian border and the Allagash Wilderness Waterway. Crisscrossed by logging roads, it is made up entirely of unorganized territory. From any mountain there is nothing to see but working forestland.

Last year, 69 percent of hunters allocated a permit in District 4 were able to tag a moose, compared to an 80 percent success rate statewide.

Allain has been guiding hunters through his Outdoor Adventure Co. since 1987, the year he purchased his camp near Elm Pond. When Allain first started coming here to hunt, moose sightings were commonplace. But last Sunday, the day before the start of the season, he and his guiding partners – Nate Fenderson and Harry Kessler – saw only moose tracks.

“Normally, along this road, you’d see 15 moose this time of day,” Fenderson said after two hours of scouting.

Allain has guided for three decades. Fenderson has guided for two decades, including for some of the state’s biggest moose.

“If anyone can call in a moose, it’s Nate. He’s half deer,” said Allain’s wife, Laurel.

None of the guides grew discouraged. Fenderson even called it a more exciting hunt.

“We have a saying,” Allain said. “If you do this (scouting) well, you will do well. Nan will get her moose Monday.”

Nan is Allain’s mother-in-law, Doris “Nan” Jackson, a 72-year-old grandmother who grew up in Appleton in a hunting family. On Monday, she would hunt for the first time, seeking the hundreds of pounds of moose meat even a small bull would provide.

She had faith in her guides. “He’s got 50 years experience hunting,” Jackson said of Allain.

At 4 a.m. Monday, the hunting party got in three trucks and drove more than an hour northeast to where the guides scouted the night before. They traveled along one of Maine’s major logging arteries, the Golden Road, before turning off and heading north on a smaller dirt road.

“This is ground zero for moose,” Allain said as they drove in the dark. “Saturday morning, I heard bellows here.”

After 5 a.m. they parked their trucks and stood in the dark listening for moose and waiting for legal hunting hours to start. When the sky lightened around 6, Allain and Fenderson headed off into the woods.

Periodically they made cow calls, trying to lure in a bull during mating season. They found deep hoof tracks in the mud. Allain pointed to broken branches beside the road that indicate where a large bull crashed through the thicket.

At times the guides held Jackson’s arm and helped her through tall grass into the woods and closer to where a moose might be. They covered the area on foot for the better part of four hours. But no moose stepped out of the woods or to answer the calls.

Still Fenderson, Allain and Kessler remained optimistic. They returned to their trucks and drove for another hour.

“That’s very moosey in there,” Allain said about brush that’s broken 4 feet off the ground.

Just after 10 a.m., they finally spotted a moose, a small bull that stepped out into the road. Fenderson gently helped Jackson around to the front of the vehicle, but the moose got spooked and lumbered off into the woods. But just before it did, Jackson looked at her son-in-law and whispered to him to fire, because Allain is Jackson’s subpermittee and can legally shoot a moose.

Allain merely smiled back at her, elated at the first real sign the hunt was on. His smile also told Jackson it’s her hunt and her moose tag to fill.

With new energy, the guides drove around a large tract of woods, trying to size up where the bulls could be moving. All the while there were no sounds of gunshot or signs of other hunters – odd for the first day of moose season.

“There are moose in there,” Allain said with confidence as he scanned the woods.

At last they stopped along a logging road on high ground. It’s a spot they didn’t scout the day before, but Allain had a good feeling. Fenderson walked deep into the woods to what he was searching for – areas where moose have bedded down and the unmistakable musty smell of bulls on the forest floor.

He returned to the group and whispered that there was more than one bull spending time there. The guides took Jackson into the woods, and for an hour Fenderson called four to five times as the guides and Jackson sat on the forest floor in silence.

But by noon, and even after another five hours of hunting, the group had only a few more fleeting moose sightings.

It wasn’t until Tuesday, after another early start, that they had success. They returned to the area where Fenderson found the musty moose smell. At 9 a.m., he made a cow call. Within a few minutes, a curious bull walked right toward the group.

“I had my gun and was in position. It wasn’t like I had to get out of a car, I was ready,” Jackson said afterward. “Their sight is not so good but their hearing is. (Allain) told me to shoot, and I hit it.”

Then Allain took a shot and the 639-pound moose fell.

Jackson said she had no doubts she would tag one.

“They knew moose were there, because (the guides) saw the signs,” she said. “There were all these signs of where the moose are laying down, the signs of where the broken branches are, of the leaves they were eating. They were positive we’d get one because of the signs.”

Allain said the party had to adjust the way they hunt.

“More hiking into the backcountry and calling is paramount,” he said.

Doris “Nan” Jackson of Portland harvests her first moose, a 639-pound bull. Jackson was hunting with the first moose permit she had won in the lottery with the help of her son-in-law, Registered Maine Guide Jake Allain, and his guiding partner Nate Fenderson, also a Registered Maine Guide. They were hunting in Wildlfe Management District 4 to the northwest of Moosehead Lake where hunting permits were cut by 58 percent by the state. Courtesy of Jake Allain

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.