We grow up, and we come to believe we don’t need fairy tales anymore.

We’re wrong, of course. The fictions created or collected by the Brothers Grimm, Charles Perrault, Hans Christian Andersen and nameless storytellers from around the world never leave us. The tales are supposedly aimed at children, but in their unexpurgated versions, they contain elements of sexuality and violence to make even the toughest aficionado of noir blanch. They’re retold or remixed in high art and popular culture, touchpoints where we can easily find commonality in a constantly churning digital sea of bewildering references. Who doesn’t know Little Red Riding or Sleeping Beauty? Who can’t relate to Cinderella?

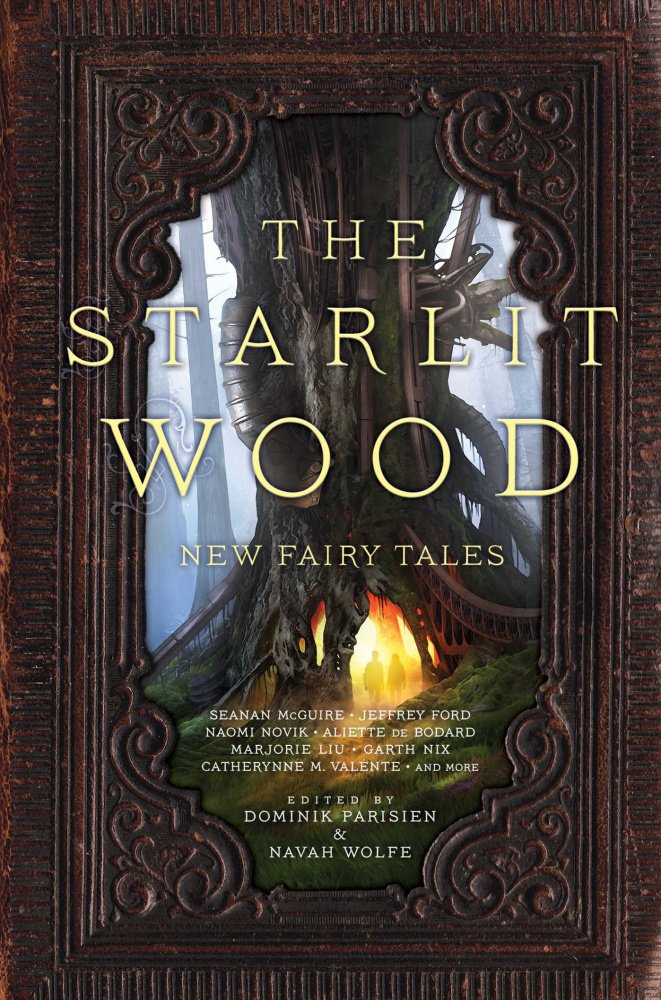

Edited by Dominik Parisien and Navah Wolfe, “The Starlit Wood” presents 18 new versions of beloved or obscure fairy tales, including “The Snow Queen,” “The Pied Piper of Hamelin” and “East of the Sun, West of the Moon.” Part of an oral tradition, fairy tales have always been subject to constant revision – conscious or otherwise. In their introduction, Parisien and Wolfe write that they “decided to run fairy tales through a prism, to challenge our readers to look at stories from an unusual angle, to bring them back into different genres and traditions, to – if you will – return them to their cross-genre roots.”

And so readers of “The Starlit Wood” receive a version of “Little Red Riding Hood” set in the desert, a post-Singularity version of “Jack and the Beanstalk” and “The Little Match Girl” presented in the form of a weird Western tale. The contributors include Seanan Maguire, Genevieve Valentine and Jeffrey Ford, as well as New England-based writers such as Catherynne M. Valente, Kat Howard, Theodora Goss and Max Gladstone.

Many familiar stories undergo major makeovers. In the sardonic “Even the Crumbs Were Delicious,” Daryll Gregory sets “Hansel and Gretel” in the drugged-out future he created for his novel “Afterparty,” focusing on the children’s terrible parents and giving the benefit of the doubt to the supposedly wicked witch. Naomi Novick, author of “Uprooted,” retells “Rumplestiltskin” from the perspective of a young woman who takes over her father’s money lending enterprise and makes a deal with a mysterious, otherworldly stranger. With “Giants in the Sky,” Gladstone adds a space elevator and a young heroine to “Jack and the Beanstalk” and presents a snapshot of life on an abandoned Earth 300 years after the Great Upload.

Some fairly obscure sources serve as springboards of inspiration. “The Mouse, the Bird and the Sausage” isn’t a likely bedtime favorite, but Charlie Jane Anders gives it a gonzo futuristic spin in “The Super Ultra Duchess of Fedora Forest.” Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Shadow” doesn’t approach the popularity of his “The Little Mermaid,” but Theodora Goss, in wondering why so few doppelganger stories feature female protagonists, puts it to good use in “The Other Thea.” Reminiscent of work by J.K. Rowling and Lev Grossman, the story follows a recent graduate of a magical boarding school as she attempts to retrieve her shadow, without which she will soon fade away.

“The Starlit Wood” includes an Author’s Note after each selection. No doubt there are readers who skip them, but each entry adds welcome personal details that aid in the appreciation of the story. In her note about “Reflected,” Howard mentions a physics article she read about “time crystals,” and how it allowed her to say, “Hey, let’s try ‘The Snow Queen’ with science in it.” It’s interesting to learn that Valente’s deeply unsettling “Badgirl, the Deadman and the Wheel of Fortune” was inspired by both “The Armless Maiden” and a bout of carpal tunnel syndrome that left the writer unable to use her hands for about five months. That Anders found it difficult to adapt her selection makes perfect sense, and it puts her story into perspective when she admits, “It was only when I decided to go fully post-apocalyptic and turn this story into, basically ‘Adventure Time’ fanfic, that it started to click for me.”

The majority of the stories in “The Starlit Wood” are by women writers, which is all to the good. Traditional fairy tales are notoriously harsh on their female characters, inflicting terrible tribulations upon them while often dismissing their ambitions and agency. The tough, complicated, contradictory women in “The Starlit Wood” largely work to save themselves and others, rather than sit passively waiting for any Prince Charming.

Beginning with “Snow White, Blood Red,” Ellen Datlow and Terri Windling edited an acclaimed series of fairy tale anthologies from the mid-’90s into the 2000s. They featured work by the likes of Neil Gaiman, Jane Yolen, Peter Straub and Joyce Carol Oates. Devised for a new generation of writers and readers, “The Starlit Wood” follows in the same tradition but brings a fresh, contemporary sensibility to the task. Each reader will have his or her favorite story, but the selections in this volume are of a uniformly high level of quality. Clever, touching, frightening, funny and frequently surprising, “The Starlit Wood” shines with magical possibility.

Berkeley writer Michael Berry is a Portsmouth, New Hampshire, native who has contributed to Salon, the San Francisco Chronicle, New Hampshire Magazine, the Los Angeles Review of Books and many other publications. He can be contacted at:

mikeberry@mindspring.com

Twitter: mlberry

Correction: This review was revised at 10:51 a.m., Oct. 24, 2016, to reflect the correct spelling of Terri Windling’s name.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.