The history of polar exploration is filled with tales of folly and heroism, in almost equal measure. Such outsized adventures prove to be excellent subjects for comics, as demonstrated by the new graphic novel “How to Survive in the North.”

Cartoonist Luke Healy weaves together three plot threads – one fictional and two based on actual events – to devise an illustrated narrative that addresses the consequences of bad decisions, loneliness, fortitude and heroism, in the Arctic and in more temperate climes.

Healy begins the book with a prose introduction to the work of Canadian explorer Vilhjalmur Stefansson, who in 1922 promulgated the notion of “The Friendly Arctic,” the theory that survival at the furthest polar reaches, where even the Inuit refused to travel, was not only possible, but easy. The feat could be accomplished, he asserted, by anyone willing to endure an all-meat diet, use only animal fat for fuel and resign oneself to the company of only a handful of fellow travelers for years at a time.

“Over the next decade,” Healy writes, “Stefansson launched a pair of expeditions, under other pretences, to prove that anyone with the right knowledge could survive in the Arctic, no matter how ill-equipped or inexperienced.”

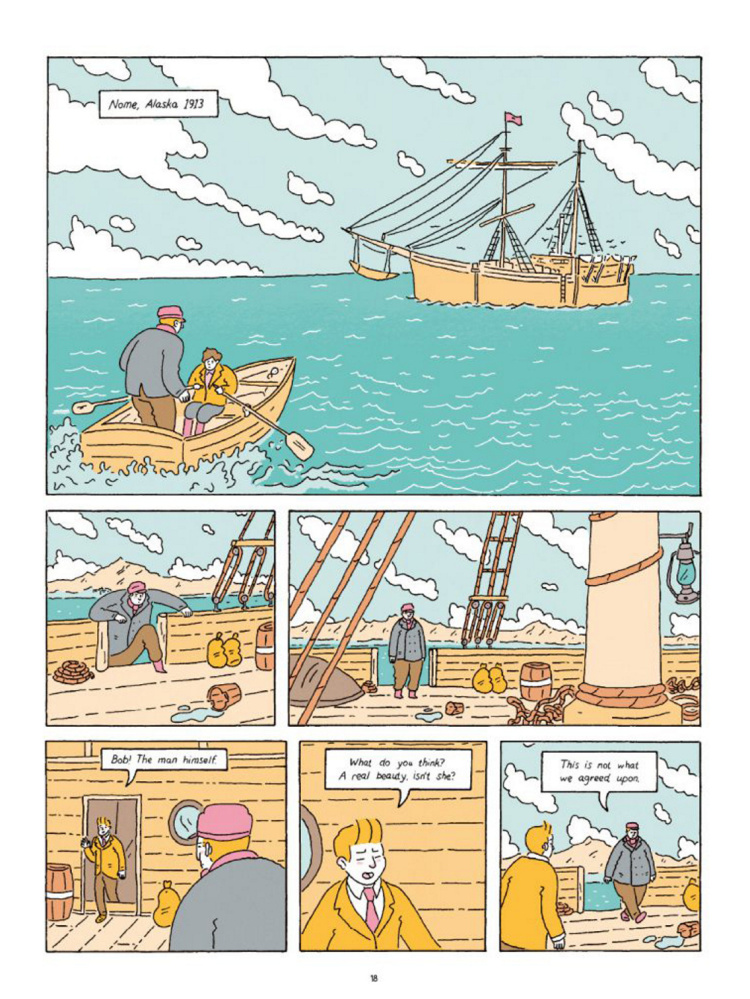

Healy begins the illustrated portion of “How to Survive in the North” in 1913, with Captain Robert Bartlett meeting Stefansson aboard The Karluk, moored in Nome, Alaska. The vessel is far older than Bartlett expected, and there’s an unexpected team of scientists taking up space and antagonizing the crew. Worse, Bartlett suspects it is too late in the season to depart without ending up frozen in the ice for the winter. Stefansson brushes all of his objections aside.

Another narrative strand, set in 1921, concerns Ada Blackjack, an Inuit seamstress who agrees to accompany four men sent by Stefansson on a trip north from Nome. Blackjack’s young son needs treatment in Seattle for tuberculosis, and she figures her salary for the expedition will be worth the year-long separation.

Finally, in 2013 at some unidentified institution of higher learning in Hanover, New Hampshire, middle-aged professor Sullivan Barnaby faces a mandatory sabbatical after being reprimanded for an affair with one of his male students. At loose ends, Sully learns that Stefansson once occupied his office, and the disgraced academic begins researching the lives of Bartlett and Blackjack.

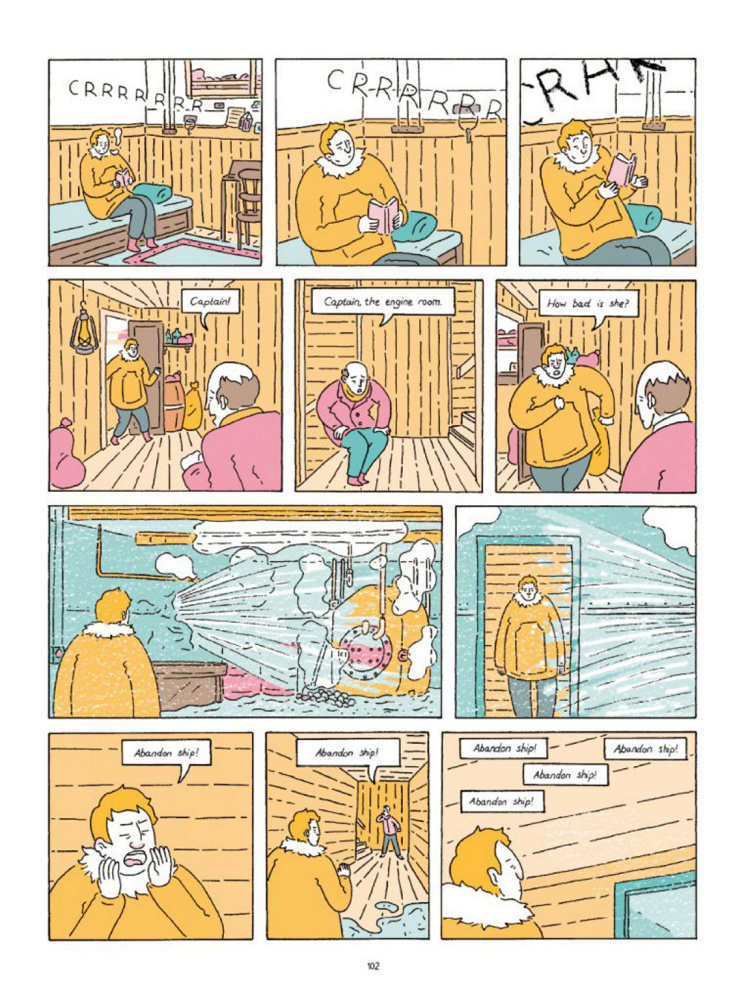

With three time frames to track, Healy keeps things simple visually, employing a reduced palette of soft red, green and yellow, for quick identification of characters and settings. The pages are laid out mostly in 12-panel grids, whose uniformity adds to the story’s feeling of rigidity and claustrophobia, while allowing the occasional multicolumn spread to open up the perspective on the enormity of the book’s subject.

With a few deftly placed strokes Healy is able to reveal his characters’ thoughts and emotions. He’s also adept at conveying the beauty and eeriness of the Arctic through the use of white space and the strength of his compositions.

Barlett’s and Blackjack’s stories are filled with physical and mental hardship and plenty of exterior and interior action. Bartlett’s main motivation is to protect his ship and its crew members, but he is undermined at nearly every turn by Stefansson’s blithe assurances that everything will turn out fine. When tragedy finally strikes, there is no mistaking the depth of his heartbreak or his commitment to putting right what he can.

Blackjack’s situation is perhaps even more dire. Marooned on an island with a critically injured crewmate and few provisions, Blackjack must put aside her own terrible homesickness, find a source of food and learn to deal with dangers that include a threatening polar bear.

Bartlett and Blackjack are complementary figures, hostages to the terrible decisions of themselves and others but determined to survive in the face of adversity. The arc of Sullivan Barnaby’s modern-day tale, however, is more problematic. As he sinks deeper into depression and lassitude, compounding his mistakes as he goes along, Barnaby may try the patience of many readers.

He eventually seems to find inspiration in the lives of the early polar explorers and perhaps develops the courage to change, but the connection does not seem entirely apt. Bartlett and Blackjack endured truly horrific circumstances that altered the rest of their lives. Barnaby experiences heartache, humiliation and loss of tenure, but how do those trials stack up against contracting scurvy or watching an acquaintance die while you’re stranded on an island for two years? The college professor’s setbacks seem minor in comparison, even as the book attempts to suggest some sort of equivalency.

One of the scientists from the ill-fated 1913 expedition asks Bartlett, “How can we go back home, Captain? After all that. How can we go back to groceries and errands and taxes? They’ll never understand. They’ll say they do, but… What’s the point of it all?”

In “How to Survive in the North,” Healy demonstrates that, contrary to Stefansson’s theories, the Arctic is anything but friendly. But he also captures some of its hypnotic grandeur and how the far reaches of this planet still pull at certain inquisitive spirits. This graphic novel heads off into unusual territory and returns with tales of tragedy and courage.

Berkeley writer Michael Berry is a Portsmouth, New Hampshire, native who has contributed to Salon, the San Francisco Chronicle, New Hampshire Magazine, the Los Angeles Review of Books and many other publications. He can be contacted at:

mikeberry@mindspring.com

Twitter: mlberry

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.